Finding the Humanity in Dance’s Legacy

An Interview with Paul Dennis

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Paul Dennis is a dancer, choreographer, regisseur, and the Chair of the Dance Department at Hunter College in New York City. He has restaged work by Pearl Primus, Ted Shawn, and Doris Humphrey, and his repertoire includes work by José Limón, Eve Gentry, Pearl Primus, and Daniel Nagrin. He has also done research into the effects of dance and neurodegenerative diseases. Here, Paul shares how his personal dance history led him to his work preserving the legacies of many of modern dance’s greatest choreographers, how his anecdotal experience led him to look closely at dance and Huntington’s Disease, and why he’s excited to be the new Chair of the Dance Department at Hunter College.

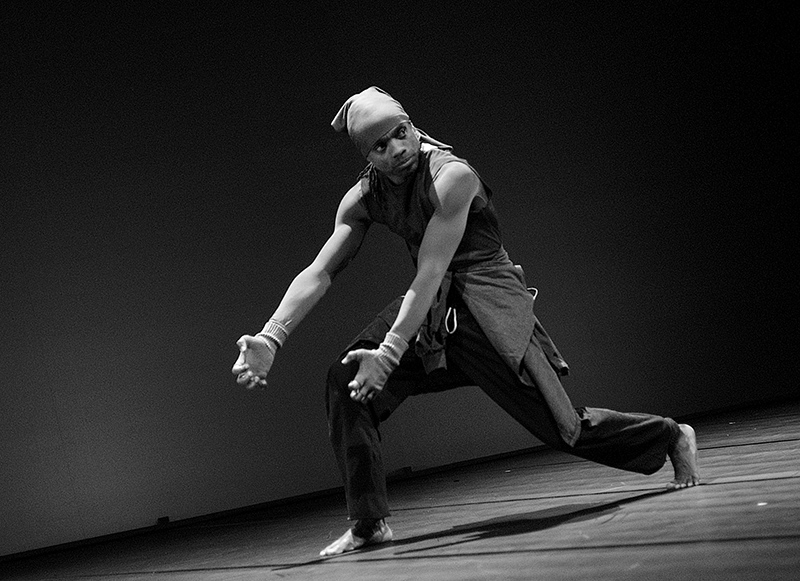

Daniel Nagrin’s “Indeterminate Figure,” Photo courtesy Paul Dennis

~~

Can you tell me a little about your dance history and what shaped who you are as an artist today?

My dance training started in my home country of Trinidad when I was eight or nine years old at the Campbells Academy of Dancing with Mrs. Heather Alcazar. I then went on to the Caribbean School of Dancing under the directorship of Miss Patricia Roe. I also performed with the Astor Johnson Repertory Dance Theater, one of the country’s best known and beloved dance companies.

In 1984, my partner Nelima Maraj and I were the winners of the Teen Talent competition, a weekly live broadcast program highlighting performing arts talent across the nation, hosted by the television personality Miss Hazel Ward Redman. The grand prize was a trip to New York City, which I used in 1986 to audition for The Juilliard School

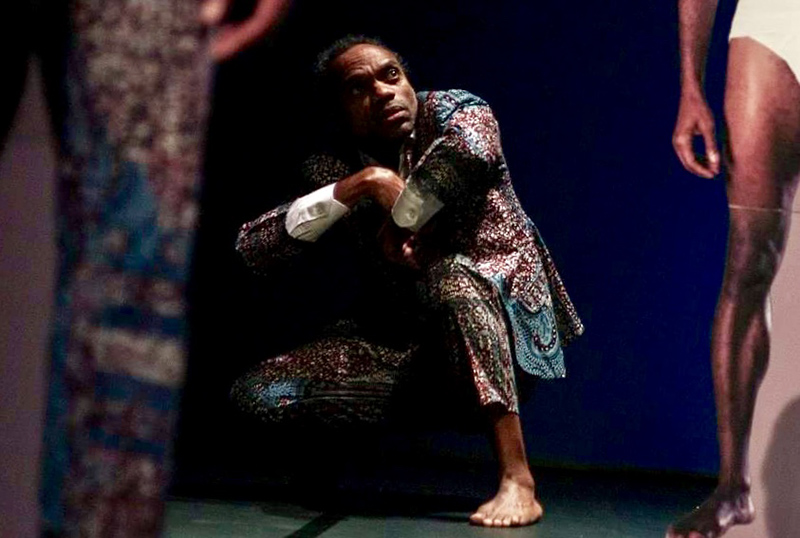

I graduated with a BFA from The Juilliard School in 1990 and within a few weeks joined the José Limón Dance Company for its five-week Eastern European tour. Afterward, I was invited to join the company as a permanent member, and I performed with them for a subsequent eight years.

My early training was as an overseas member of the Royal Academy of Dance in London. At that time, we followed a defined syllabus against which we were tested every two years in order to advance to the next skill level. This shaped my attention to rigor, self-discipline, and the respect for form and structure in training. As an artist today, I enjoy the boldness of classical, modern, and contemporary forms and their manipulation, and I gravitate to this as I create my own work.

Later in my career, Contemplative Dance created a huge shift in my artistic philosophy. I increasingly sought out ways to incorporate improvisational and contemplative forms as a critical aspect of dance making and performance.

Probably the most evident influence today came from my years in the Limón Company. The philosophy and humanity of the technique influenced my own life on and off the stage. Limón’s statement, “I believe that we are never more truly and profoundly human than when we dance” resonates with me, and the same approach I use in my life on-stage, I believe has been interwoven in my life off-stage.

José Limón’s “Chaconne,” Photo courtesy Paul Dennis

As far as my interest in history and repertoire, I’m not sure if there was a watershed moment. The more I taught, the more that interest developed. It was obvious to me that people needed to learn the legacies of choreographers. It was never a feeling of, “We have to save this before it’s lost.” Rather, it was a natural progression from doing the work to teaching the work and finding its value.

During my first year at Juilliard, my dance history class watched Limón’s The Moor’s Pavane, one of the most profoundly moving artistic creations I have ever seen. I’ve seen it many times, and I choke up every time I watch it. During that class watching The Moor’s Pavane, I thought to myself, “I want to do work like that.” I have always believed in the humanity of dance to move people. If I was so moved, other people could be moved, which led me to teaching and restaging. It is no accident that “moving” has a double meaning.

For someone unfamiliar with the term, what is a regisseur and how did you become one?

The term identifies someone who, by skill and experience, is qualified to pass on the creative legacy of an artist. Because of my understanding and skill with Limón’s philosophy and choreography, I have the honor and privilege to restage a number of his well-known dances on individual artists and dance organizations, including academies and professional companies. The same is true for a few of the works by Pearl Primus, Ted Shawn, and Doris Humphrey, who was Limón’s teacher.

Why works by those choreographers?

In the case of some of these choreographers, like Pearl Primus, I think it is important to have these works shown because of the ways they were marginalized in the past, and because of my own experience as an Afro-Caribbean man needing to explore his own Blackness and how that might intersect with my audience who might need to explore their own Blackness or Whiteness.

All the works I reconstruct have humanity in them. My approach and philosophy about the works I create, perform, or research are necessarily about humanity. They help us to question our assumptions and look closely at our biases or prejudices. It goes beyond art for art’s sake, although there’s room for that as well.

Eve Gentry’s “Tenant of the Street,” Photo courtesy Paul Dennis

I study the work of Ted Shawn for historical purposes. He ran an all-men’s dance company when men dancing wasn’t favored. Again, the work he did was about the human experience. Even when some of his work was abstract, it still spoke to humanity. When I have performed the work, it was never about virtuosity, but about what was being said or communicated.

If I am moved by a work, I am going to trust that the audience is going to feel something too. The audience will react differently, but it’s not my job to determine what they are getting. It’s my job to give what I’m giving and trust they are receiving something meaningful. It’s hard to prove because there’s no data, but that’s why it is art.

How did you build your performance repertoire consisting of works by such dance greats as José Limón, Eve Gentry, Pearl Primus, and Daniel Nagrin?

Needless to say, I have a long and intimate history of doing the Limón work. While in the Limón company, we worked with Daniel Nagrin, and now, with permission from the trustees of his estate, I perform three of his solos.

I became intimately familiar with Primus’ work in 2009 when my mentor Peggy Schwartz invited me to learn her choreography, to be performed at the 92nd Street Y in NYC, along with the release of “The Dance Claimed Me: A Biography of Pearl Primus”, written by Peggy and Murray Schwartz. Primus is Trinidadian by nationality and was a seminal figure in American modern dance, bringing African forms and philosophies to her studio, in her lectures, and in her choreography.

In addition to Pearl Primus, my solo concert also includes work by Reggie Wilson and Deborah Goffe, whose creative research encompasses the experience of people from the African diaspora. It was time for me as an artist and as a person of African descent to do some deep soul-searching.

Deborah Goffe’s “Bespoken,” Photo courtesy Paul Dennis

What did that soul-searching include?

The search is still active. I grew up in Trinidad in a very religious environment. At the time, activities outside the realm of my particular faith were judged as pagan or witchcraft. There’s a whole African culture that I wasn’t open to. Now, no one explicitly told me not to dance these dances, but the environment I was in somehow suggested that I shouldn’t participate in dances of the African experience, like the Orishas, the spirits of the Yoruba religion originating from West Africa. I remember being in the Astor Johnson Repertory Dance Theater and there was a dance called Yemanjá, in honor of the Mother of all Orishas, and I asked the choreographer to excuse me from performing because it involved an experience I was unfamiliar with and afraid of because of my religious beliefs.

By the time I was an adult living in America, I had to reckon with the fact that I didn’t know what Black dance was all about. I hadn’t put myself in the place where I was interrogating my experience as a Black dancer. While I was studying for my MFA at Purchase College, I asked Reggie Wilson if I could do one of his solos. We had a long conversation about it, and he asked why I wanted to dance it, and I told him I didn’t know what it meant to be a Black dancer in my bones. I hadn’t interrogated my own philosophy about dancing and being Black. I did his piece, and I’ve been changed since then. It wasn’t just performing the dance; it was questioning my life, my art, my artistic research.

Given how ephemeral choreography is, why is it important to you to preserve choreographic works?

It is true that choreography lasts for a short moment in time, it is fleeting. And that is its strength! That one moment of movement or gesture will never be seen again, ever! The power of that is in fact the advantage of the art form. A performer who embodies an eternal moment in every single moment of performance… there is nothing more truthful than that.

The chorographic works are a vehicle of humanity, and that is why it is important to preserve them. When I perform Eve Gentry’s Tenant of the Street, the movement is sparse and deliberate, giving me time to live each unit of space and time, and giving those who witness the opportunity to find themselves in each unit of space and time. It’s a convergence of my space-time reality with the witnesses’ space-time reality, and this combination changes people. That’s why it is so important.

I also understand you’ve done research into the relationship between dance and neurodegenerative diseases. Can you share more about what prompted you to pursue this research?

During my studies towards my designation as a Certified Movement Analyst (CMA) at the Laban Institute of Movement Studies (LIMS), I was invited to visit Tewksbury Hospital in order to propose an alternative art program in support of people with traumatic brain injuries. Although I had heard of Huntington’s Disease (HD), I did not know much about the way it affected people’s lives and the lives of their loved ones. On my visit to the campus, I was introduced to the HD residents, and particularly because the most obvious symptom of the disease is the movement disorder, I immediately thought that my work as a movement analyst could be of benefit.

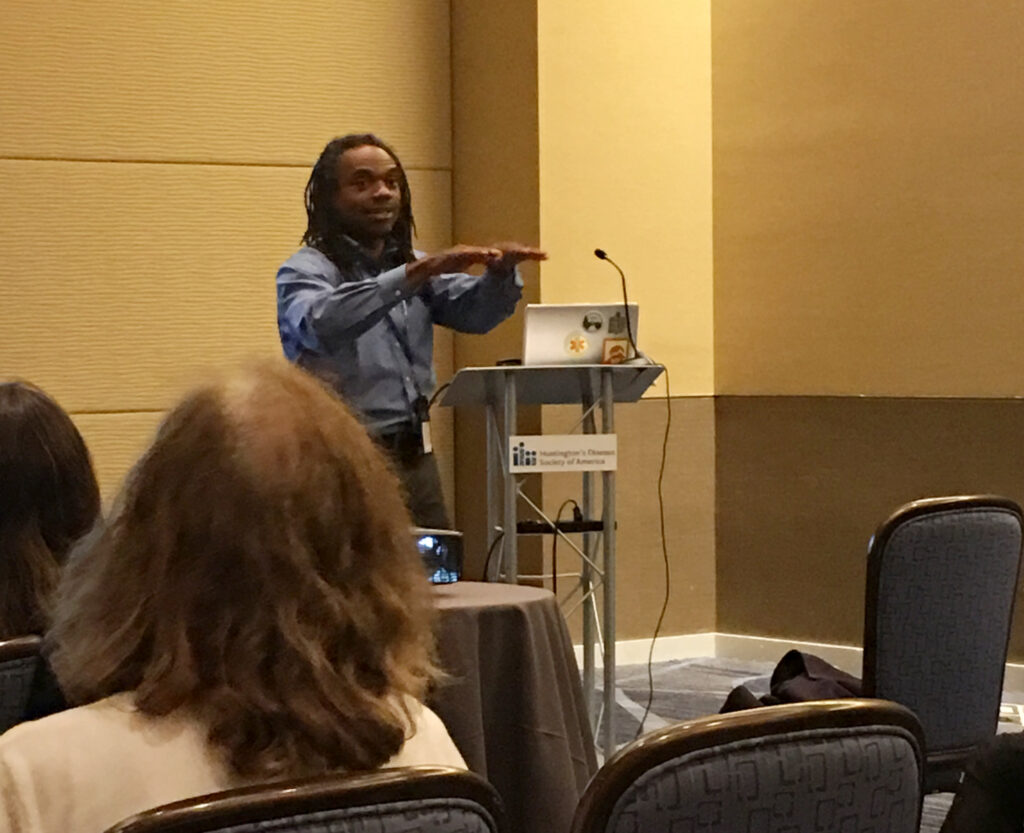

Paul presenting Dance for Huntington’s Disease (DfHD) at the HD Annual Conference

With the support and encouragement of my friend and colleague Terry Laub, who was at the time the leading occupational therapist at Tewksbury Hospital, I began working there twice weekly to design a movement curriculum that incorporates the Laban/Bartenieff Movement Systems in an effort to help alleviate some of the disease’s symptoms.

What have been some of your findings?

To date, my findings are only anecdotal. However, I have applied, and await notification (fingers crossed) for a grant sponsored by Huntington’s Disease Society of America. My proposal includes a collaborative effort with the HD Center of Excellence at Columbia University to conduct a 12-week clinical trial that will determine the efficacy of dance to improve the daily living of people with HD.

At Tewksbury Hospital, I alternated between group sessions and individual sessions. Anecdotally, I saw the way dance supported the community and their emotions; everyone would say how it changed their day. They were more energized and more open to relationships and community. One of the residents said she hates going to the dentist, but before one appointment she did some of the breathing and movement exercises we did in the dance classes, and then she flew through the appointment with ease. There were things of that nature where it was clear dance was having an emotional and psychological impact.

I use the Laban Bartenieff system to create and design the exercises that help people with HD explore all three dimensions of space: sagittal, horizontal, and vertical. We create dances that incorporated all those aspects by building in one aspect at a time.

Previously, people thought the brain was static in its function, but what we’ve learned is the brain can heal and navigate its neurons and synapses to overcome dysfunction. Dance for HD is aims to harness the capability – the “plasticity” — of the brain to heal itself. Through movement and dance, the brain can rewire to function beyond disability.

What’s next for you? Do you have a project or focus you’d like to share more about?

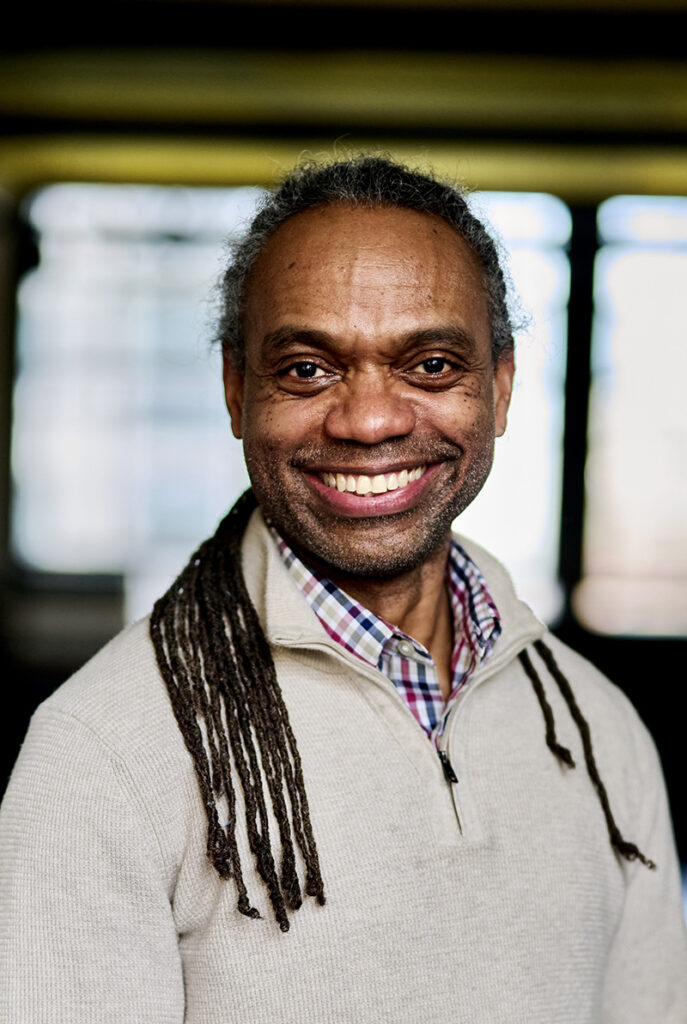

Being the Chair of the Hunter College Dance Department is my primary focus, which I approach with real excitement and optimism. Hunter Dance is poised to be the destination of choice for affordable, expansive, and diverse, dance studies in New York City.

Our mission statement is “Hunter Dance is a radically diverse community cultivating an expansive dance education driven by persistent inquiry, to elevate dance as a vehicle for positive change in the world.” Who wouldn’t be excited about that!? It harkens back to what I was talking about earlier regarding the humanity of art. If everybody who sees dance is changed a little bit, we change the world. Dance is an interrogator of our assumptions; dance is a vehicle for democracy. Hunter College’s Dance Department is poised to be a leader in the field, and I am privileged, honored and proud to be here doing this. When I was invited to the position, one of the reasons I said yes was because I was blown away by the students – their intensity, intention, diversity, creative research. Their idea of movement includes but goes beyond the proscenium. I want to be part of and facilitate that movement!

Otherwise, as I mentioned earlier, provided that I am honored by being awarded the grant, I will also be focusing on supporting the HD community with my Dance for Huntington’s Disease (DfHD) research.

And I believe I still have at least one more solo concert in me if I can convince my knees that they are younger than they think. I might be on stage again in the not-too-distant future.

Photo courtesy Paul Dennis

~~

To learn more, visit paulanthonydennis.com.

4 Responses to “Finding the Humanity in Dance’s Legacy”

Thank you so much for this brilliant interview. I don’t know how else I would hear about the work going on or hear the wisdom of dance-centered colleagues!

Paul,

Thank you for your profound “statement”

I am filled with joy for you and those students you share your honesty, heart, and knowledge.

Best Ever,

Catherine Fellows

Indeed! Thanks Tara!

thank you for this article — i am so happy to learn about Paul Dennis and celebrate his new position. a true force for good – for dance and humanity

cheers

and great good fortune

Comments are closed.