How Cultural Production Functions

An Interview with Ninoska M’bewe Escobar

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Ninoska M’bewe Escobar is a dance scholar and Postdoctoral Fellow in Dance currently based at the University of New Mexico. Before joining the world of academia, she had a long career as a dancer and choreographer in New York City as well as a teacher and program director at The Ailey School. Here, she discusses her focus on bringing more attention and awareness to the legacy of Pearl Primus, as well as why it is important to teach the history of dance forms alongside technique in order to understand how cultural production functions.

This interview is part of Afro Diasporic Dance in College Settings, a series of interviews with dance professors who teach Afro diasporic dance forms in American college dance programs.

Photo courtesy Ninoska M’bewe Escobar

~~

What was your introduction to dance and what have been some highlights or pivotal moments in your dance career?

My first exposure to dance was in the context of my family’s attention to cultural practices. It was through dancing with elders in my family. I am an immigrant from Honduras, and I moved to the US as a young child. I understood then that if there was a birthday or baptism or even a death, it could be marked with music, singing, and dance combined with testimonies and prayers. Like a lot of African descended communities in Latin America, my acculturation was certainly influenced by Catholicism, but also by traditional African derived practices, which gave a great deal of attention to ancestors as well as a spirituality that derived from Yoruba culture. I had a great grandmother whom we called Yaya, a name I’ve found may indicate “elder,” “woman,” or “priestess.” So, my first introduction to dance was in the context of family cultural practices and Afro-Latin American identity.

I did not start professional dance training until I was much older. When I was in high school, I had a friend who studied modern dance with Rod Rodgers in New York City. I saw her perform and I was blown away. Early in my career, I engaged with Mr. Rodgers when I was transitioning from what was then called “ethnic” dance to modern and contemporary dance.

I began my formal dance training at the Clark Center for the Performing Arts in NYC in the late 1970s. My first teacher of modern dance was Marjorie Perces, an original dancer from Lester Horton’s company. I began dancing with Loremil Machado and Jelon Vieira, who are credited with introducing American audiences to capoeira. They were on the faculty at the Clark Center and had created a company, Capoeiras da Bahia. Later, Loremil formed his own company, the Loremil Machado Afro-Brazilian Dance Company. I danced with Loremil and Jelon until the mid-1980s.

It was Marjorie Perces who introduced me to Alvin Ailey. Marjorie felt I needed another kind of training, so I started studying at The Ailey School in the early 1980s. Mr. Ailey took an interest in me. I didn’t dance in his company, but he became a mentor. He introduced me to other choreographers including Alfred Gallman, whom he’d also mentored, and Louis Falco, who hired me to dance in the original Fame. Later, I danced with one of Falco’s principals, William Gornel, in his company for a couple years.

I worked in NYC for three decades. As I developed my career, I decided to focus on developing my own work as a choreographer. I had a couple companies in New York before disbanding them. I had young children at the time, and it was very difficult to keep a company supported while raising children.

I was also doing a lot of teaching and community engagement. I spent a good deal of time from the mid-1990s until about 2009 working for the Ailey organization, both as a teacher in the school and as a program director. I co-directed the Ailey/PPAS pre-professional program. I also directed AileyCamp in New York and Miami for several years. Then I became a national facilitator of the humanities curriculum Revelations: An Interdisciplinary Approach that used Mr. Ailey’s ballet Revelations to explore societal issues. I did that from the early 2000s until I made the decision to start graduate school in 2009.

Because of my involvement with the Ailey organization, my interest in Black dance history was broadened. In my own work as a choreographer, I found myself returning to topics and themes like the development of Black culture in the US, the problems of political and social oppression, the problem of racism, the problem of gender oppression, along with spiritual themes. Because of this expanding interest in dance history and theory, I began to think about obtaining graduate education. I felt it would be important for me to develop as an historian. The John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin gave me a generous fellowship, which enabled me to enter the Performance as Public Practice program in the Department of Theatre and Dance. I completed an MA and then went into the PhD program.

From 2016 to 2021, I worked at the Five Colleges in western Massachusetts. I spent two years at Amherst as a Consortium for Faculty Diversity Scholar. I then finished my dissertation and from 2019 until last spring I was teaching part-time at Mount Holyoke, Smith, and Amherst. Last spring, I accepted an opportunity to come to the University of New Mexico, which was very exciting. The Inclusive Excellence Fellowship, a two-year research appointment at UNM, supports my work on both sides of dance practice and theory.

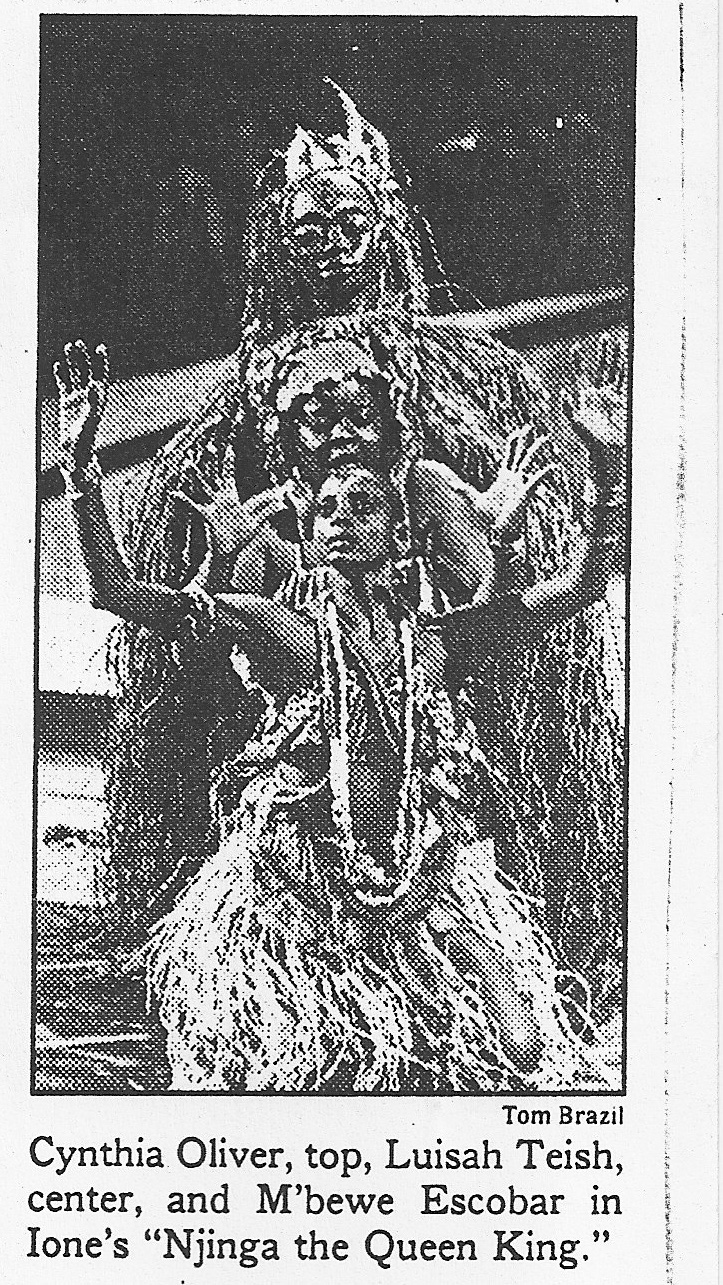

Cut out from the New York Times

What is your current dance practice? How often do you teach, perform, and/or choreograph?

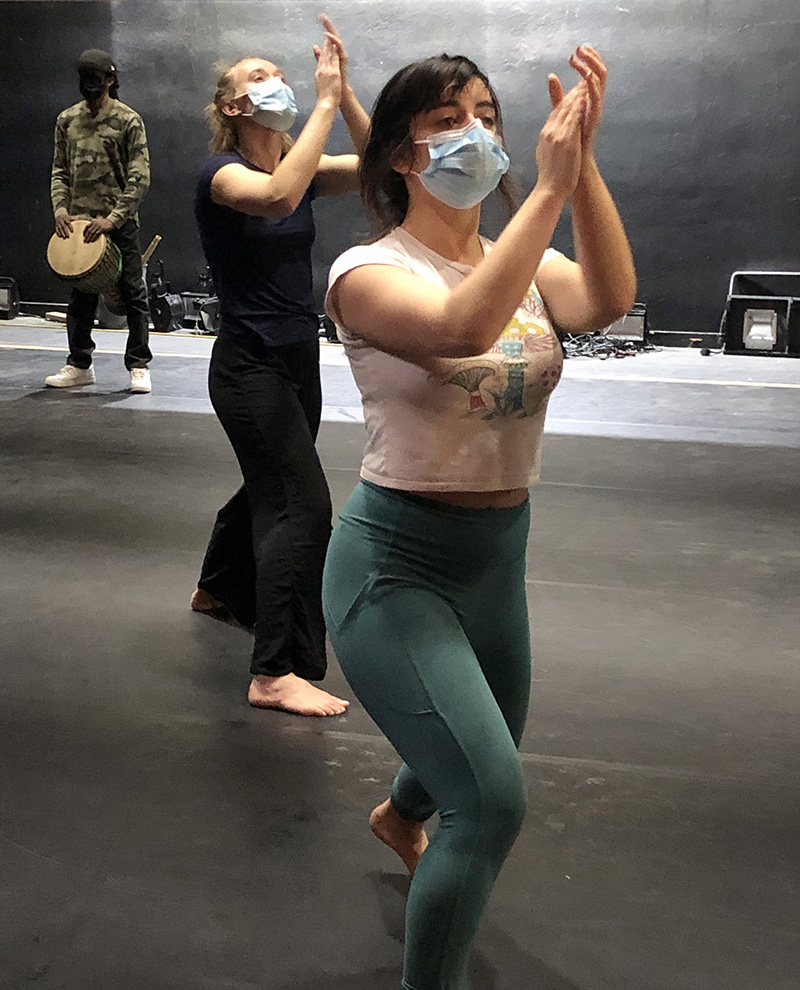

I no longer perform. Since I started my companies back in the late 1990s, my own performing career has been sporadic. Currently, my creative work is in training and choreographing for dancers at UNM. This semester I am teaching dance writing. Last semester, I worked with my department’s performing ensemble and created a work for them that was recently performed. Next semester in the fall, I will be teaching contemporary and modern technique with African diasporic impulses.

My approach to contemporary dance helps students acquire African diasporic dance vocabulary and aesthetics, increased rhythmic facility, musicality and grounding. When I teach technique, be it African-based dance or contemporary, I involve dance history. I want my students to have a sense of how dance forms come into being and that all dance is cultural dance, including ballet. I teach from a social and political perspective that recognizes dance as a cultural formation, and that it reflects the values and traditions of specific cultures. That includes the dominant Euro-American culture in dance education, through ballet and modern dance.

Do you have an upcoming project or research focus you’d like to share more about?

In the area of African American dance history, there has been some critical attention to Pearl Primus, the Caribbean American dancer, choreographer, and anthropologist. However, Katherine Dunham is still much more well known. My engagement with Primus started when I was a child encountering her photograph in a who’s who encyclopedia of American woman. Her photograph was so striking I had to find out more about her.

Much later, when I began my decades of immersion into African derived dance forms and modern dance, I learned more about Primus and developed questions and curiosity about her that informed my graduate research project. I wrote a dissertation based on my research about her, and in my continued research, I am documenting the recent reconstruction of one her works that is rarely seen, Michael Row the Boat Ashore, by Paul Dennis who is now the Chair of Dance at Hunter College.

By focusing on Primus’ work and legacy, I’m attempting to expand her significance, not just at the point of her emergence in the 1940s and her work educating audiences and the American academy about African culture, history, and aesthetic practices, but also to connect her to the current moment in the US in the work of many artists who are making significant social and critical connections through art. Many choreographers have been inspired by the model she created for the solo dance form, by her approach to using research to create dance, and by her attention to Black experiences. She’s extremely relevant to the contemporary moment. Primus was clear she was not concerned with entertainment but rather with aligning herself with progressive politics. I’m working to create a portrait of her that centers her as a political artist and Black feminist icon.

Now I’d like to dive into your perspectives on academia. How long have you taught in academia? What courses have you most often taught?

I started teaching in academia in 2011 at UT. I developed a new course in African diasporic dance and theory. It included technique in the studio and history in the classroom. I did that for two or three semesters. When I started the heavy work of research for my dissertation, I stopped teaching.

In 2016, I moved to Amherst College and taught African American dance history, general dance history, and African American theater history. At Smtih and Mount Holyoke, I taught West African dance technique and African American dance history.

Since you started teaching in academia, have you seen more opportunities for students to study Afro diasporic dance forms? If so, what exactly has changed?

At UT, when I taught African diasporic dance and theory, I’m not sure how long it had been since the department had even offered a credited course such as mine. The course I taught was entirely new. There was African dance available in the Austin community, but not in the department at the time. Students and some faculty took this class.

When I moved to the Five Colleges, Theatre and Dance at Amherst was excited to have courses not regularly offered in the department. However, I regard practical and historical/theoretical courses in Black arts to be essential and it is hard to understand how any theatre and dance department can justify their absence.

If there’s been an expansion of attention and inclusion toward this kind of work in theater and dance departments, I think it’s been in direct response to the demands of students who want broad cultural diversity in curriculum as well as instruction and mentorship from more faculty of color. I think they go hand in hand, a result of that desire and demand by students of color and other students who are interested in the history of culturally derived dance forms besides ballet and modern. In most institutions where I’ve taught, ballet and modern are still considered the foundations of Western and American dance. I contest that as a historian and teacher.

Across the country, lots of students are aware of West African dance. It’s quite popular, both community-based instruction and in certain departments. The migration of African artists to the US since the 1970s has made dance from Africa more familiar. Before that, the main exposure was Afro Cuban or Afro Caribbean. But now, lots of students have been exposed to West African dance.

Photo courtesy Ninoska M’bewe Escobar

When I was at the Five Colleges, my courses were credited, of course. At Amherst, for example, the program is diverse, offers a “core,” and includes studio and historical/theoretical courses. Here at UNM, the concentration is either contemporary or flamenco, but students are exposed to other techniques and are required to take at least three credits in either jazz, hip hop, or West African dance. And it’s repeatable, so students can get more exposure if they’d like.

I think generally, dance forms beyond ballet and modern are not considered foundational, and that is a problem. These kinds of “extraneous” techniques have informed American dance to a great extent, and not just in the current moment, but historically. The gods of early 20th century American dance borrowed and appropriated “ethnic” forms that were foreign to their own cultural identities to create new work. Not considering them foundational to American dance ignores the potential that they offer to professional dance training.

Where you’ve taught, are Afrodiasporic dance forms treated as equally valuable as Western dance forms like ballet and modern? If not, what changes would you like to see in college dance curriculums?

As an example, West African dance training is considered significant in The Ailey School because the Ailey aesthetic quotes and relies on a multiplicity of techniques. Those students have to learn ballet, modern, jazz, African, etc., and they have to do them well.

But I wouldn’t say that’s the case in every conservatory. And in the case of higher education, it depends on the program and department whether other forms are treated equally.

Why is it important for dance students to be educated in Afro diasporic forms? How does it create a better or more well-rounded dancer?

African American culture is American culture. I am not the only historian or artist scholar or educator who recognizes this. African American cultural production has been investigated to a great extent, and it is concrete knowledge that African American culture has informed what has broadly come to be called American culture. Why then shouldn’t students study African American and Black diasporic dance, theater, literature and performance? I go into the history of African American performance by investigating the politics, the economic implications, and the social concerns of creating a theater of representation for a marginalized people. Students need to see that bigger picture of how cultural production functions and operates.

Any other thoughts?

I am really interested in connecting my work to communities outside the university. I am in the beginning stages of planning a small conference to commemorate the United Nations Declaration of the Decade of People of African Descent, which started in 2015 and is ending in 2024. So, we’re nearing the end of the commemorative decade. According to the resolution, the International Decade aims to recognize the important contributions of people of African descent worldwide, is positioned against racism and intolerance, and promotes human rights and social justice and inclusion policies. This conference would focus on the importance of the arts and diverse cultural participation to the advancement of global human rights and environmentalism, and aims to build greater connection to communities beyond the university by dialoguing what it means to produce art in connection with people’s everyday lives and their human rights.

Photo courtesy Ninoska M’bewe Escobar

~~

To learn more, www.ninoskamescobar.com.

Ninoska M’bewe Escobar is an artist‐scholar and Postdoctoral Fellow in Dance in the Department of Theatre and Dance at the University of New Mexico. She specializes in Black diasporic theater, dance, and performance, and investigates how bodies carry history and memory and how cultural heritage and social experiences shape identities and artistic practices. Escobar is documenting the work and legacy of Caribbean American dance pioneer Pearl Primus (1919-1994), a seminal figure in the development of American modern dance, the solo dance form, and the use of dance to promote social justice. Her current project examines the recent reconstruction of the rarely seen dance work, Michael Row the Boat Ashore, created by Primus in 1979 as she reflected upon the 1963 bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Escobar was a guest panelist for “Celebrating Pearl Primus” at the University of Massachusetts Fine Arts Center in October 2021. The “Celebrating Pearl Primus” conversation may be viewed here.

From 2016 to 2021, Escobar was affiliated with the Five College Dance Department in western Massachusetts where she taught African American and world dance history, African American theater history, and West African dance at Amherst College, Smith College, and Mount Holyoke College. In 2018, she organized the dance symposium African American Dance: Form, Function, and Style! which explored the history and practice of African American dance through public talks, master dance classes, performances, and films, with a keynote address presented at Amherst College by preeminent dance scholar Dr. Yvonne Daniel. Previously, she co-directed the Ailey/Pre-Professional Performing Arts School Program in New York and directed AileyCamp in New York and Miami. She was a lead facilitator of the humanities curriculum Revelations: An Interdisciplinary Approach, which utilizes Alvin Ailey’s signature ballet Revelations to engage students and educators in examining societal issues impacting their lives and communities.

Escobar has a professional background as a performer and choreographer, creating original works for the all-female New York-based performance groups Life Force Dance and M’word!, presented at the Joyce Soho, the Theater of the Riverside Church, the Neuberger Museum of Art, and The Knitting Factory in New York, among others. She was a principal dancer in the companies of legendary Brazilian capoeiristas Loremil Machado and Jelon Vieira, performed with Nigerian Jùjú music trailblazer King Sunny Adé, with Le Ballet National Djoliba, and with Jamaican reggae superstars Third World during their 1980s tours of the US. Her film and theater work include performing in the original cast of MGM’s Fame (1980), the Brooklyn Academy of Music Nextwave Festival production of Njinga the Queen King (1993), and in numerous concert stage productions and venues including Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Jacob’s Pillow, and the Santa Fe Dance Festival. As a choreographer, she created the dances for Reza Abdoh’s The Law of Remains (1992) and the Nuyorican Poets Café production of Pepe Carril’s Shango de Ima (1994), which won an Audelco award for Outstanding Black Theater Choreography.

One Response to “How Cultural Production Functions”

Outstanding and well over due stance- THANK YOU!!

Comments are closed.