Discerning The Diversity and Multiplicity of Dances within Africa

An Interview with Momar Ndiaye

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Momar Ndiaye is an internationally recognized dance artist from Senegal who has taught and toured his work both in the US and abroad. He is currently on faculty at the American Dance Festival, and assistant professor at Ohio State University. He has also been developing work with his own company, Cadanses, which is based in Senegal, since 2004. Here, Momar talks about the political, technical, and social aspects of why Afro diasporic dance forms deserve equal footing with European classical dance forms in American college dance programs, and why he is interested in creating more opportunities to support emerging artists in his home country.

This interview is part of Afro Diasporic Dance in College Settings, a series of interviews with dance professors who teach Afro diasporic dance forms in American college dance programs.

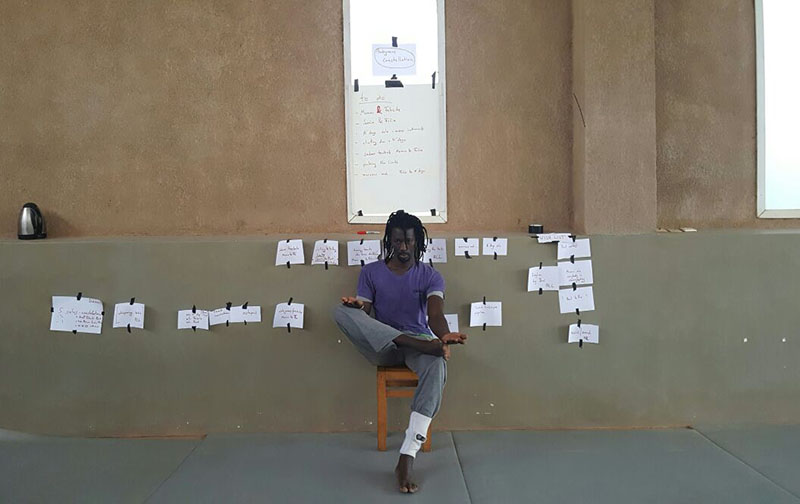

Photo by Felix Burkel

~~

What was your introduction to dance and what have been some highlights or pivotal moments in your dance career?

You can tell from my last name, Ndiaye, that I’m from Africa, and to be specific, Senegal. It is a majority Black country and is divided into six major linguistic groups. I belong to the largest, Wolof. I was born and raised around dance and music. Our society is divided into castes, and each caste has somewhat of a function. I am not a griot. Griot, or “Guewël” in Wolof, are in charge of history, culture, and arts. The caste system is disappearing because modernity and Western culture is taking over, but it is still anchored in some communities. Regardless, I’ve always been around dance because African society is shaped that way: If you’re happy, you dance. If you’re sad, you dance. It’s a way of expressing emotion. You dance through rites of passage such as circumcision, etc.

My dad is a music collector; everything from Latino music like salsa and bachata to R&B, international music, and local music have always been a part of my life because of his record collection. And then on TV every Saturday night were variety music and dance shows. I fell in love with Michael Jackson when I was a kid. I happen to be talented in terms of looking at movement once and reproducing it, so I would imitate his dance moves for my dad’s friends. I would also do this with a local singer who was pretty famous, Moussa Ngom. He was a fervent advocate for the confederation of Senegal and Gambia. He always wore two different colored socks, one color for each country. My dad’s friends would ask me to imitate him singing and dancing.

In middle school, I joined the school theater group. We would rehearse after classes. Because it was a school theater company, everything we did was connected to history or education. With friends, we started a b-boy group. I actively started dancing onstage using hip-hop styles when I was 15. This was a group we created with friends from the neighborhood.

In Senegal, there was a national dance competition. We auditioned and passed. That’s how my national career started as someone actively rehearsing and performing. My parents allowed me to dance recreationally as long as it was not interfering with my studies. This competition was over the summers, so we’re talking about 14-15 hours of rehearsals every day spread over two months. I did that dance competition for five years. It was a space where I learned most of the African dances that I’m able to perform right now. Because it was a national dance competition, we would have to research the dances and the music. Sometimes it was easy, but sometimes we would have to go seek help from folks immersed in those dances.

One of those mentors asked if I wanted to dance more seriously. He helped me join a private dance team where I learned jazz and Afro jazz. It was more Western. It escalated until I founded my own dance company in 2004.

My company, Cadanses, got funded to work with the International Research and Development NGO, which worked with communities in developing countries. They had a program called Scientific Culture and I got support from them to make work that was directly speaking to environmental issues. As a choreographer, I was immersed in the research environment. Scientists would explain things to me and have me look through the microscope to see how elements interact. And then I would make a version of what I learned using dance and music, so when illiterate people watched the piece, they would understand the mechanics. I did this for about three years before diving into contemporary dance.

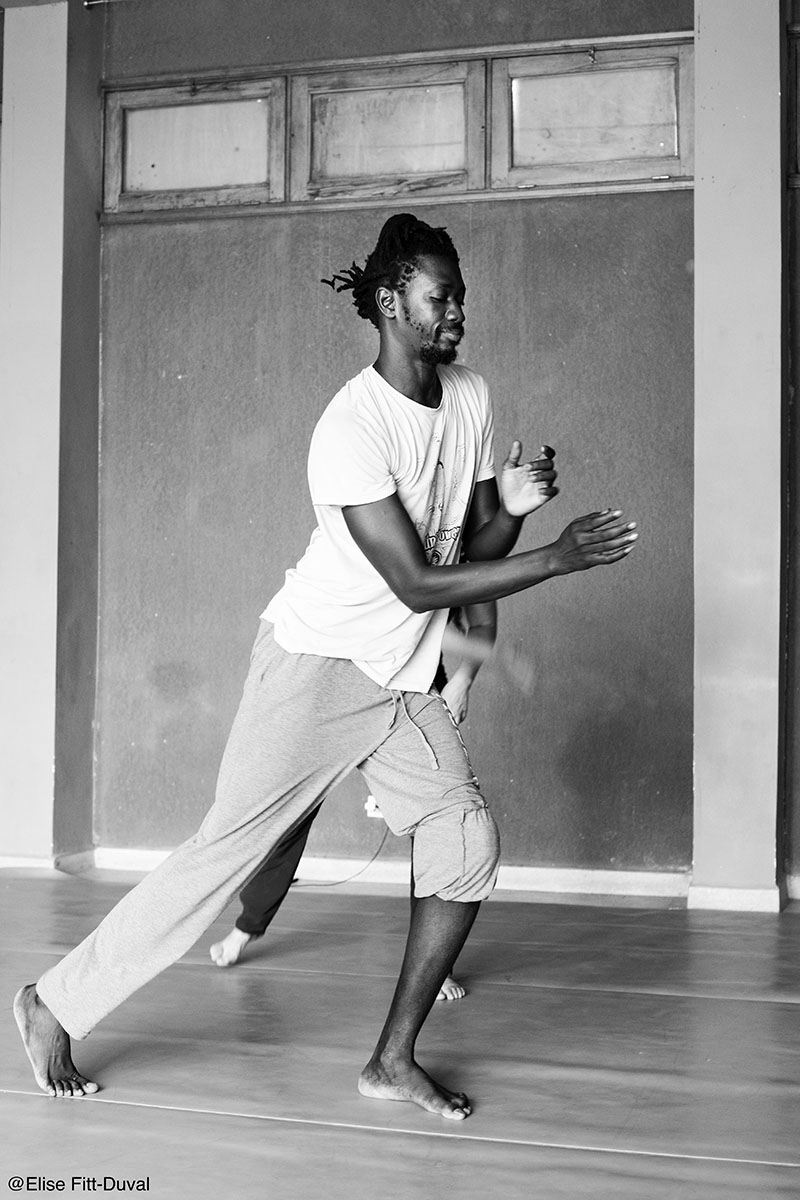

Photo by Elise Fitt-Duval

I joined an international dance company based in Senegal called “Premier Temps.” Through their program AEx-Corps, I had opportunities to train more. To me, training is very important. I don’t see dance as something rigid; it always evolves. That program was to prepare me to join the company while at the same time developing a choreographic vision and a more diverse and open technical background. For about three years, I was always immersed in a creative environment, working with choreographers from different countries.

That’s when the problems with my family started. I have a dual degree in Quantitative Techniques of Management-Economics, and Marketing: Commercial Action. My family was upset I wasn’t using my degrees. Eventually I came to the US and got my MFA in Dance, which was another important highlight of my career.

In 2012, I got the chance to go to ImpulseTanz and be part of what they call danceWEB, a selective and competitive program. Thousands apply from all over the world and that year I was one of four Africans selected. It was an opportunity to interact with 60 other young international choreographers in one place, dancing and talking about dance every day. It was an important moment in my career in terms of learning about European aesthetics and how they can coexist or be in tandem with African aesthetics.

I developed professional relationships and kept networking. Before I got my MFA, I would be invited to teach master classes. But I started teaching semester-based classes when I started my MFA in 2014.

Photo by Katia

What is your current dance practice? How often do you teach, perform, and/or choreograph?

I teach every day basically. In a normal semester, I have three to four courses: a contemporary course, an African/traditional course, and a repertoire course which is teaching technique and choreography with an expected performance. Basically, I am a studio-based professor, whether it’s teaching how to make work or teaching technique.

Can you share more about your company Cadanses?

Cadanses was initially created as an association, meaning a nonprofit. Last year I created an annex of it because an association status doesn’t allow certain activities. Now there is Cadanses and Lacadanses. Lacadanses is now an official company that is separate from the association, but they are still interconnected.

Cadanses is an acronym in French for “company African de danses.” The idea was to provide support and training to folks who may not have access to training in dance and related fields that gravitate around dance, like sound design, theater, and lighting. Cadanses offers a space for training and supporting folks who are trying to make it as artists. The other side of Cadanses is creating dance and performing, so there is a community side and a performance side.

Photo by Andreya Ouamba

The idea behind Lacadanses was to create an annex that would handle the business side of the creative industry, so the community aspect could remain in the nonprofit side. In order to avoid conflicts of interest, I needed to create a separate but related organization that has its own legal registration, recognized by the Senegalese government. Everything I do in this way is still based in Senegal. In the US, I do things as freelance or officially connected to Cadanses. One of the goals of coming to the US was to build a bridge between artists. I’m still very attached to that idea, and it is happening slowly.

I have not had much time to create work with my company recently, but my dancers have been making, and I’ve been supporting them. I haven’t had time to choreograph for Cadanses because I’ve been developing a bigger training program with partners from Europe which is called Share/Creative Africa. It started from an idea that is very simple: When I am in Senegal and I make work, I need to go to Europe to find a lighting designer. I can make the dance in Senegal, but everything related to production has to come from Europe or the US. We have very few lighting designers in Senegal, and they don’t have the resources to do the job. The idea is to train folks to create, hoping they will be mentors for future generations. Looking at it from a longer perspective, we will not need to go to Europe for relevant sound or lighting design. I also want to create a space where we can talk about dance as a creative industry, not necessarily needing the French institute in order to have a platform to perform. Everything can be produced and showed locally. That’s the idea behind Share/Creative Africa. I have partners from Burkina Faso, Slovenia, Cameroon, and other places. That and my other professional obligation in the US are why I have not had time to choreograph for Cadanses. It’s a lot to manage.

Now I’d like to dive into your perspectives on academia. How long have you taught in academia? And what courses have you most often taught?

I’ve taught dance for film and dance documentation, traditional African and African urban forms, as well as contemporary and Afro-contemporary, improvisation, and composition. I have taught at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Denison University, University of North Carolina at Asheville, and Ohio Wesleyan University. I have also been on faculty at American Dance Festival since 2018 teaching in both professional and pre-professional programs.

Since you started teaching in academia, have you seen more opportunities for students to study Afro diasporic dance forms?

There are more and more opportunities for people to be immersed in the world of Afro diasporic dance forms. Universities are revising their curriculum to make it a little more diverse and inclusive, as well as trying to treat equally all the forms that used to be under the umbrella of world dance. It is time to pay tribute to the contribution of Black dance forms. We cannot talk about contemporary or modern dance without talking about what Black people have contributed. Even ballet. I don’t believe there’s a form in this world that has not been influenced by Africa. It is time and it is happening gradually and broadly. By allowing a space to be carved into institutions for students to be trained in traditional African dance and African vernacular dances, we’re mirroring what we could qualify as an ethical globalization. We are starting to be more inclusive in our practices and in our curriculums. It’s happening in many major universities.

Photo by Andrew

Where you’ve taught, are Afro diasporic dance forms treated as equally valuable as Western dance forms like ballet and modern? If not, what changes would you like to see in college dance curriculums?

Before, all these forms were put under the umbrella of world dance. And then you’d have ballet level 1, 2 and 3 that are required courses. Now what’s happening, at least here at Ohio State, is our students must have four semesters of African dance. That’s equal to the requirements for ballet. And they can elect to take extra. There is at least a trial of equalizing or offering more space for these forms to exist.

There are difficulties. We are carving a space for this form to exist, which means we must have resources like people who can teach and make sure those forms are taught effectively. There are not many of us right now doing it, but at least we’re opening the space more and more. As a result, there are more international students who were fearful before of not getting the support they’d needed in researching traditional African dance or African American vernacular. The more we train people, the more we open the field, and more people will teach later.

It’s a system inside of a system that is learning how to coexist. In order to be a teacher at a university, there are requirements. Most people who live in the US who are dancers and want to teach get an MFA. Getting the degree is a necessity. I came into the US as someone who was already making my way in the international community. Getting my MFA in dance was a necessity to learn about American college dance culture. It doesn’t mean I consider myself a master in African dance or any dance. I know enough to understand that a dancer must be humble, since dance in general is a living and breathing being that evolves constantly.

Photo by Andrew

In the African world, the idea of “master” is very tricky. How can we be a master in dance? If you ask that to an African, they will tell you it’s impossible. We are talking about thousands of dances. You can only aim to be a master of one or two dances. We discern the diversity and multiplicity of dances within Africa. Each dance represents something that’s attached to a community. As a Wolof, I can talk about my culture’s dances. I can learn other dances, but then my connection to the dance and culture would be different. I consider myself someone who knows and is still learning. There’s a humility that African dance requires. You know what you know, and you acknowledge that it changes. There are areas you may not know, and these are areas of research.

Why is it important for dance students to be educated in Afro diasporic forms? How does it create a better or more well-rounded dancer?

There’s the political side: When we talk about modern dance, what do we mean? Are we qualifying only Western forms of modern dance? Can we at least sit down and say there are so many elements in European modern dance that come from Black communities? Can we talk about nuances and acknowledge places of origin? Can we pay tribute to the origins of those that were deported and chained by learning their actual dances?

The other side is technical. I train dancers to operate in multiple spaces. Learning dances from Africa reinforces everything a dancer needs to be relevant in 2022, like the nuances in footwork, polyrhythms, polycenter-ness, speed, resilience, respect, and humanism.

Photo by Natalie Fiol

I’m no longer going to make the case for African dance. Using Eurocentric dances as comparative reference is a passive way of placing African forms under Eurocentric forms. Someone asked me once in an interview what would be the benefit of teaching African dance in an institution. I said I did not understand the question. He said that in modern dance, there are progressions to see concepts such as body halves. I said that the most basic motion in African dance would encapsulate all those elements. Many dances from Africa are polyrhythmic; the feet, torso, and arms are all marking specific rhythms. Three rhythms existing in one body in motion – tell me that’s not a relevant skill for a dancer. We as instructors of African forms see our students struggle in our classes and face the difficulties of finding strong dancers from here capable of dancing in our choreographic work, which undeniably means there is a technical gap that needs to be filled. I was trained as a polyvalent dancer and that is what I want for my students.

The other side is the social aspect and the community reinforcement. This includes the social justice and equalizing space we always talk about. This is all stuff that’s inherently in every African dance class you find. We start in a circle in the beginning. We acknowledge each other. We celebrate each other. We cannot operate without acknowledging ourselves and others. In African dance classes, we’re already doing what we are trying to do right now in the US, which is undoing racism.

~~

To learn more, visit www.momarkndiaye.com.

One Response to “Discerning The Diversity and Multiplicity of Dances within Africa”

fantastic!

Comments are closed.