On the Intersections of Dance, Theater, and Disability

An Interview with Nadia Adame

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Nadia Adame is a dancer and actor originally from Spain and currently based in Vancouver, Canada. She has worked in choreography, theater, and film throughout North America and Europe, and enjoys working across disciplines. Here, she describes her experience pursuing dance and theater as a person with a disability, how both fields are slowly shifting toward better inclusion, and how theater and dance can and should inform one another.

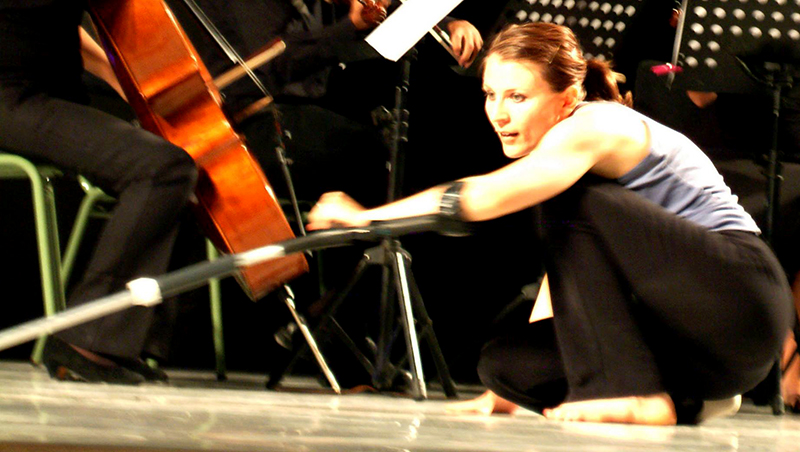

Photo by German Anton

~~

Can you tell me a little about your performance history and what shaped who you are today?

I always liked dancing around my house. When I was about six years old, a friend of my mom who was a professional flamenco dancer looked at me and said to my mom, “This girl needs to be in some dance classes.” At age seven, my mom enrolled me in the Royal Conservatory of Dance and Drama in Madrid, Spain, where I’m from. I studied flamenco and ballet, but my focus was flamenco.

At age 14, I had a car accident and was in the hospital and in rehab for a few years after that. I stopped dancing but my passion for dance never left me. So I decided to choreograph. I didn’t think that dancing with a disability was an option then. When I was 19, I got a few friends together and choreographed an hour-long show based on flamenco and what I thought at the time was contemporary.

I wanted to expand my knowledge and travel, as well as figure out my new body and possibilities, so I decided to go to the US and study at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Because of my disability, some of my professors discouraged me from doing dance courses even though I had trained for seven years at the conservatory in Spain. Instead, they directed me to the theater department. That’s where I started getting exposed to acting.

After graduation, I applied to many companies, and among them was AXIS Dance Company in Oakland. At the time, it was directed by Judy Smith. Of the 20 companies I contacted in the US, it was the only one that called me back. Judy asked me to come and audition. It was amazing and opened my future as well as my idea of what a performer could be. My career took off with AXIS. That’s where everything really started.

One of my best friends from childhood is a professional actor, so I was always exposed to theater and film through him. At university when I went to the theater department, it was difficult because of the reason for it, but it was not completely alien to me. While I was in AXIS, I looked for theater performances in the Bay Area that I could be a part of. I worked with small companies doing acting in addition to dancing with AXIS.

Film came naturally to me because I wanted to learn how to edit my own videos and make the camera move with the dance. I taught myself. I observed and talked to people. It was a natural evolution.

How would you generally describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

I am a multidisciplinary artist; I see art through a variety of lenses. For example, there’s the movement of the camera, or the acting eyes of the dancer. When I was a kid, my uncle played flamenco guitar and my grandfather used to sing. I am multidisciplinary artist because of the exposure to different forms I have had in my life.

Can you share some projects that have been particularly important to you?

There are so many experiences from different times in my life that meant different things, it’s hard for me to narrow it down. A dream come true was dancing with Baryshnikov at the Kennedy Center while I was with AXIS. I always admired him as a dancer. When I was with him in the studio, I couldn’t believe it.

I was the co-artistic director of a performing arts company in Spain called Compañía y, and one of the projects we did was to bring dance and music to hospitals in Madrid, especially children’s hospitals. The kids were like I was when I had my car accident, some of them in the hospital for long periods of time, either because of accidents or chemotherapy. The body changes and you don’t know how to use it anymore. We brought dance into the hospital and worked with kids on how to relate to their new bodies and work with who they are now. That project was important to my heart because I knew how they felt in that time.

I was very proud of the work I did while I was co-artistic director of Compañía y. I performed in a piece around 2005 called koläzh by Mark Swetz who was the other co-artistic director of the company. We devised a play based on the Czech artist Jiří Kolář’. The producer of the piece was a foundation called Fundación ONCE. They are focused on people with low or no vision. The way we approached the production was by using smells. It was in the fall so we put fallen leaves all over the theater so when the audience came in they would hear and feel the crunching of the leaves. We also wore a variety of shoes that made sounds that reflected different movements. It made me think differently about performance.

I choreographed a piece on AXIS Dance Company in 2018. It was about baggage and how all of us carry baggage in our lives. The piece was called Broken Stories and I designed the space so there was luggage and letters all over. The choreography told the story of my grandparents who had a difficult life. They lived through a war and under a dictatorship, and the piece explored how their stories were carried down to me even though I did not personally experience the war or dictatorship. By hearing them talk about it, it became part of who I am.

How does your dance experience intersect with your acting and film work and vice versa?

I love movement of any kind, and I try to bring that into acting, performing, and the camera. How a character eats or gets dressed in a play are movements and can be performed differently if the character is anxious or calm, for example. All of that is part of a complete picture that as a performer I need to represent.

When I work with the camera, I see it as a dance. The camera becomes my partner in addition to the other actors. How do I relate to the camera, and how does the camera move? Is it always static? To me, that’s not interesting.

I always bring all my artistic experiences to the table because they complete each other. There’s the trope of the dancer’s face being neutral, for example. I think that’s changed a little over the years, but there are still dancers who have blank faces when they dance. They only express from the neck down. That really bothers me. It could be a little smile or a certain focus – small details that add to the dance. It’s the same with actors, who often feel like they’re a talking head and their body doesn’t move or relate to those expressions. To me, dancing and acting must go hand in hand to make the art more interesting and complete.

Photo courtesy the artist

How have you seen representations of disability change in mainstream media during your career?

Representation of disability in the media is extremely important because it reflects society. While growing up, I never saw anyone like me, and that’s why I thought dance wasn’t possible for me after my accident.

I think it has changed very slowly. But at least it’s moving forward. I always try to look at the positive side. At least there are studios that are casting people who used to not be represented, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be people with disabilities. Generally that means someone who is from a different ethnicity than white or who is LGBTQ, which is fantastic and definitely needs representation and support. But disability is always the last thing people think about. Non-disabled performers are still cast as disabled characters. And disabled performers are never cast in lead or mainstream roles. Actors with disabilities should be able to play roles that have nothing to do with disability; they should be able to play the lead in a love story, for example, and the fact that they’re disabled is as important as their hair color.

Is that change different from more experimental or alternative art spaces?

I think so. Alternative art spaces and more fringe spaces are always more open to new ideas. I just wish it was more in the mainstream too so it’s more visible. Not many people go to alternative art performances. People who go to the opera or go see a Hollywood movie don’t generally see experimental art. It would be great to see disability in more mainstream spaces for the normalization.

There are choreographers like Arthur Pita in the UK. He was reworking one of his pieces that had all non-disabled dancers. He called me and said, “Nadia, I can’t find anybody without a disability who gives me what you give me. Can you come?” He wasn’t going to crip the old piece, but he was going to create a new piece based on the old piece. He cast me not because of my disability, but because he didn’t see it as a block. That’s been happening slowly, but it’s too slow for my taste.

I’ve mostly worked in Europe and North America, and it’s different in every place. There are places where disability is still a shameful thing. In other countries, that concept is changing and there are laws to protect people like me. But there’s no perfect region in the world where we’re 100 percent equal. Things are advancing slowly. There is still a lot to fight for.

What’s your next project/focus?

I’m currently working on two projects. One of them is a community-based project in Vancouver, Canada, directed by Hila Graf where the participants have written monologues about their experiences of the pandemic lockdowns. It’s very interesting because everyone who is part of the project are immigrants, so they talk about the separation from their home countries and their families during the pandemic. I’ve been brought in to do movement with them. We have recorded their monologues and movements in a forest, and now I am editing the project.

This summer, I will also be teaching the intersection between theater and dance at a workshop in Sweden to people with and without disabilities. This was supposed to happen last year in person. But of course, anything that was supposed to happen in 2020 got postponed. I’m teaching the workshop remotely this year instead.

~~

To learn more about Nadia, visit www.nadiaadame.com.

Photo by Matt Gilmore

7 Responses to “On the Intersections of Dance, Theater, and Disability”

Congratulations! Great article and admiration for your diligence, and your unwavering purpose.

Great interview. What an impressive career!

Oh Nadia, what an amazing story. Thank you so much for sharing. Good luck withbyour new projects.

Enhorabuena por esta fantástica entrevista. Un paso más para que te conozcan y para que el mundo vea que hay que dejar de poner límites. Se hace camino al andar!!!

Always an inspiration! Great article.

Way to go Nadia! You know we always have your back!

Fantastic Article..im glad I read this

Comments are closed.