Kris Lenzo: “An Opportunity to Educate”

BY SILVA LAUKKANEN; EDITED BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Kris Lenzo transitioned to dance after more than two decades as a wheelchair athlete; he was a national champion in both wheelchair basketball and wheelchair track multiple times. Since 2003, he has danced with MOMENTA in Chicago, Illinois. He has performed at Spring to Dance in St. Louis several times and has also appeared in Dance Chicago, Duets for my Valentine, Bodies of Work’s Disability, Art and Culture Festival, Counter Balance (I-VII), and at Chicago’s Disability Pride Parade. Kris is also a teacher in MOMENTA‘s EveryBody Can Dance! workshops and was a 2015 3Arts awardee.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

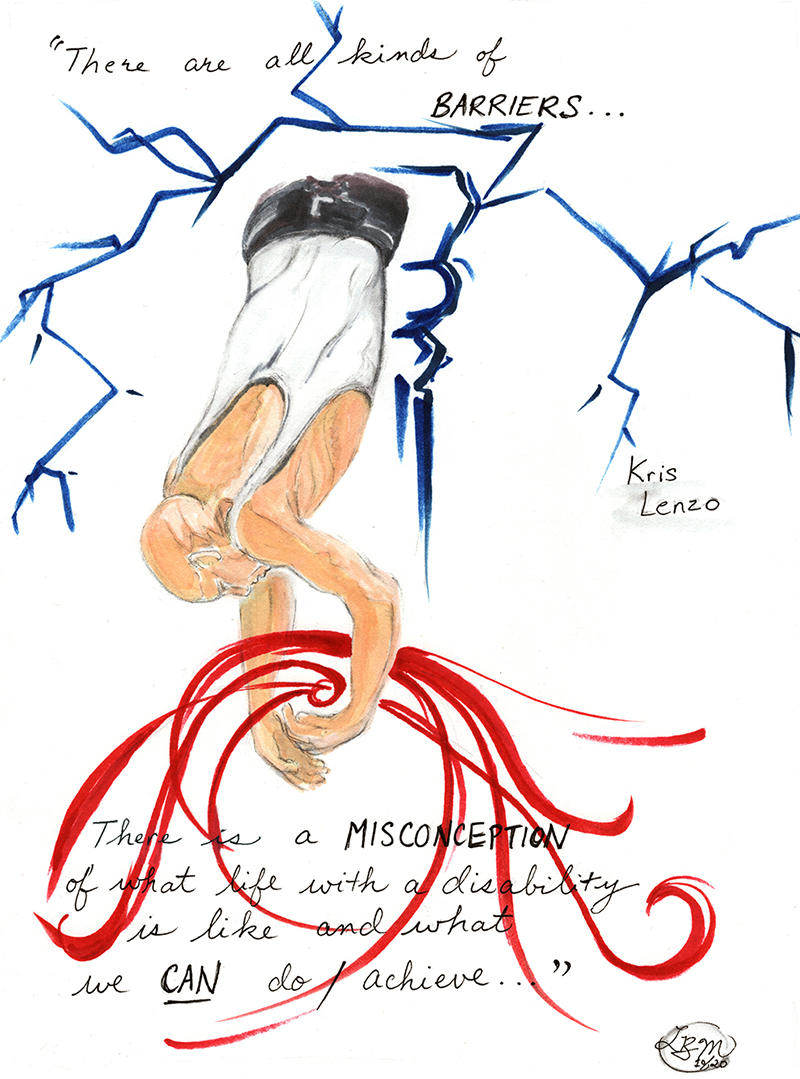

Image description: Kris is depicted as suspended upside down from the waist by blue lightning-like lines of energy. His arms reach below him with his hands gently encircling red swirls of energy. He is wearing a white tank top. The quote, “There are all kinds of barriers…” starts at the top and ends at the bottom with, “There is a misconception of what life with a disability is like and what we can do/achieve…”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

My youngest daughter, Olivia, went to preschool at the Academy of Movement and Music, a local dance and music school. I asked the owner, Stephanie Clemens, to install a ramp to the building so I could pick up my daughter. Stephanie was also the co-founder of MOMENTA Dance Company. To Stephanie’s credit, she raised money to put in a ramp, as well as made the bathrooms wheelchair accessible and put in an elevator. At that point, Stephanie wanted to commemorate making the building accessible by creating a dance for MOMENTA featuring dancers with and without disabilities, and asked if I would like to be in it. My initial reaction was, “No, not in the least,” but then she said if any of my daughters wanted to be in it with me, they could. Olivia (who was four or five years old at the time) said she wanted to be a part. Stephanie also asked me if I knew any other dancers in wheelchairs. I had seen Ginger Lane perform in a production somewhere, so I recommended her. And then there were two twin sisters who would be a part. One had cerebral palsy and the other didn’t have a disability. The five of us did a piece choreographed by Larry Ipple. This was in 2003.

Dancing was a lot more fun and interesting than I thought it would be. The piece had an original composer and live music. This was my first time performing, and I just thought that was how it always was. It was a nice way to start dancing. Playing basketball, I often was out of town at games, whereas the dance rehearsals were half a mile from my home, and I got to spend more time with my daughter.

As far as pieces that I’ve done that are highlights, one of them would be Ashes in 2004, the year after I started dancing. In the piece, I hung upside down for 10 minutes and lifted this dancer repeatedly. It was challenging to figure out how to support me upside down and we tried various options. The piece ended up being really unique. The audience could only see half my body, and they couldn’t see the apparatus supporting me, so it was like I was hanging from the clouds. We did the piece until 2013, and performing it was always a highlight.

MOMENTA has performed maybe six times at Spring to Dance in St. Louis. Every time we’ve gone, it’s always had integrated work. It’s a well-run festival with two theaters showing two concerts a night. High caliber companies are presented, and the tickets are affordable. That was always a highlight to be a part of. Another highlight was being a part of Bodies of Work’s Disability, Art, and Culture Festival, organized by Carrie Sandahl, in 2006 and 2013.

But the biggest highlight of my career was receiving the 3Arts Residency Fellowship in 2015. It was $25,000 and really validating artistically.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

The amount of time my dance practice takes can vary quite a bit. It’s not a full-time job, but it disproportionately feeds my soul. Dance connects me to art. I don’t usually take classes, but I teach in MOMENTA’s EveryBody Can Dance! workshops. There are six or seven of those each year. When there’s an upcoming production, I am in rehearsal more, and then my schedule is less intense afterward. I go to contact improv on Sundays sometimes, and I exercise on my own in order to have a smaller list of what I can’t do anymore. I was 43 when I started dancing and I’m 60 now.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

“What?” Sometimes people think I’m joking. They might ask, “How does that work?” I’d say confusion and curiosity are the most common responses. Now that I’ve been dancing with MOMENTA for so long and I know so many of the families who have come through the school, people often tell me they saw me in a show. Still, a much higher percentage of the population knows what wheelchair basketball is versus what disability or integrated dance is. I look at it as an opportunity to educate someone.

There are all kinds of barriers that people with disabilities run into – architectural, medical, economic – and two of the barriers are a misconception of what life with a disability is like and what we can do/achieve, as well as a social awkwardness. A goal of mine is to reduce those barriers and create more connection between people with and without disabilities. I want to create more awareness as well as increase comfort-level; so many people without disabilities are uncomfortable around people with disabilities. I would like to see a world in which everyone knows five people with a disability. Then we start to look at people with disabilities and just be curious and relaxed. Performances can play an important role. Someone might think, “I’ve never seen a person with a disability dance before; what else can they do?”

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

One response I hear a lot that rubs me the wrong way is when people see me perform and say, “I didn’t even see the wheelchair.” I’m like, “You should have!” In some ways, it can be viewed as a compliment, but it’s a backhanded one. I consider my wheelchair an extension of my body, both when I played basketball and when I dance.

I did sports for about 20 years playing basketball, road racing, and track, and road racing got the most coverage. At the time, wheelchair racing was somewhat new. There was a fair amount of inspiration-porn back then. But for dance, I can’t recall that narrative being applied to me. Maybe that’s because Chicago has such a vibrant disability arts scene in general. I’m the fourth disabled artist to get the 3Arts award, which is specifically geared toward people of color, women, and people with disabilities.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities?

Probably not. It depends on where you are. Here in Chicago, we’ve got a strong disabled dance community.

However, I remember a woman who was a double amputee came to one of our EveryBody Can Dance! workshops and wanted to come again the following week, but we hold them only once a month and, even then, only six or seven months out of the year. It’s hard to build momentum only once a month. Even in places like ours that have a robust disability dance community, the training is limited.

The number of dancers is also limited. This speaks to the problem of identifying, grooming, and developing new dancers. There’s an inherent problem in that, as far as people who acquire disabilities from an accident, they’re much more likely to be male because we can be a bit reckless, relatively speaking. And most guys are not interested in performative dance. I choreographed a piece 12 or 15 years ago, and I had the kids tell me a little about their backgrounds before we got started. This boy Tommy said he’s been dancing since he was nine or 10, and there are usually barely any other guys besides him. He said it used to bother him that his dance classes had two guys and 16 women, but it doesn’t anymore.

Beyond teaching in MOMENTA’s EveryBody Can Dance! workshops, I’d personally like to get involved in teaching dance at local rehab hospitals. With dance, people become less self-conscious and start moving freely. The spirit of it gives people more stamina than they think they have. They improve their wheelchair mobility and expressiveness too.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

Definitely. Most of the performances I’ve been in have been integrated settings where there are dancers with and without disabilities, but I’ve also been part of concerts where every piece was disability dance. Whatever works. When I used to play wheelchair basketball, I enjoyed watching other teams play. I thought it was interesting enough to watch that it could have been more popular than it was. But how do you bring people to it? Any way you can introduce people to this work makes sense. Reaching one person is valuable. I don’t worry much about how extensive the audience is. It’s out of my control.

It’s great if we have dancers with disabilities performing professionally. But just like with sports where most of the kids playing won’t go professional, it’s great just to get kids and adults with disabilities involved in dance, especially in inclusive dance settings, just so they learn that everyone can dance and realize the many benefits of dance.

What is your preferred term for the field?

For me personally, I like “dancer” or “disabled dancer.” As far as the name of the field, I kind of like “inclusive dance.” It sounds inviting.

When I first became disabled, the idea of being “temporarily able-bodied” didn’t resonate at all with me; either you were disabled or not. Since then, my dad got Parkinson’s before he died, then my brother Peter had a head injury that resulted in epilepsy. A friend of mine who was really into fitness and health had a skiing accident and is now a quadriplegic. At that point, I understood and appreciated the term. The aging process is disabling too.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

I’d say overall it’s getting more well-known because there’s been more coverage of dancers with disabilities, like when AXIS was on So You Think You Can Dance. People either know about the field or they don’t. I still run into some who haven’t heard of disability dance.

Any other thoughts?

I remember once talking about dance with another disabled athlete who said he liked watching dancers because he could see them stretching their envelope of movement vocabulary. Twenty years later when I started to dance, I remembered and appreciated that comment.

Pictured: Kris Lenzo, photo courtesy of the artist

Image description: Kris is pictured onstage with a standing dancer. His wheelchair is oriented to the side toward the standing dancer, and she is facing him. She has one foot en tendu behind her and one arm bent at the elbow behind her. Kris is wearing a red shirt and the standing dancer is wearing a long black dress.

~~

Learn more about MOMENTA by visiting momentadances.org.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

2 Responses to “Kris Lenzo: “An Opportunity to Educate””

Thanks Larry! We’re thrilled to feature Kris!

I’ve been fortunate to share the stage with, choreograph for,and watch Kris dance through out his career. This article presents Kris as the artist/ educator he has become. Congratulations to Kris and to Silva for this presentation about a man who dances.

Comments are closed.