Krishna Washburn: “I’m Cutthroat; This is My Career”

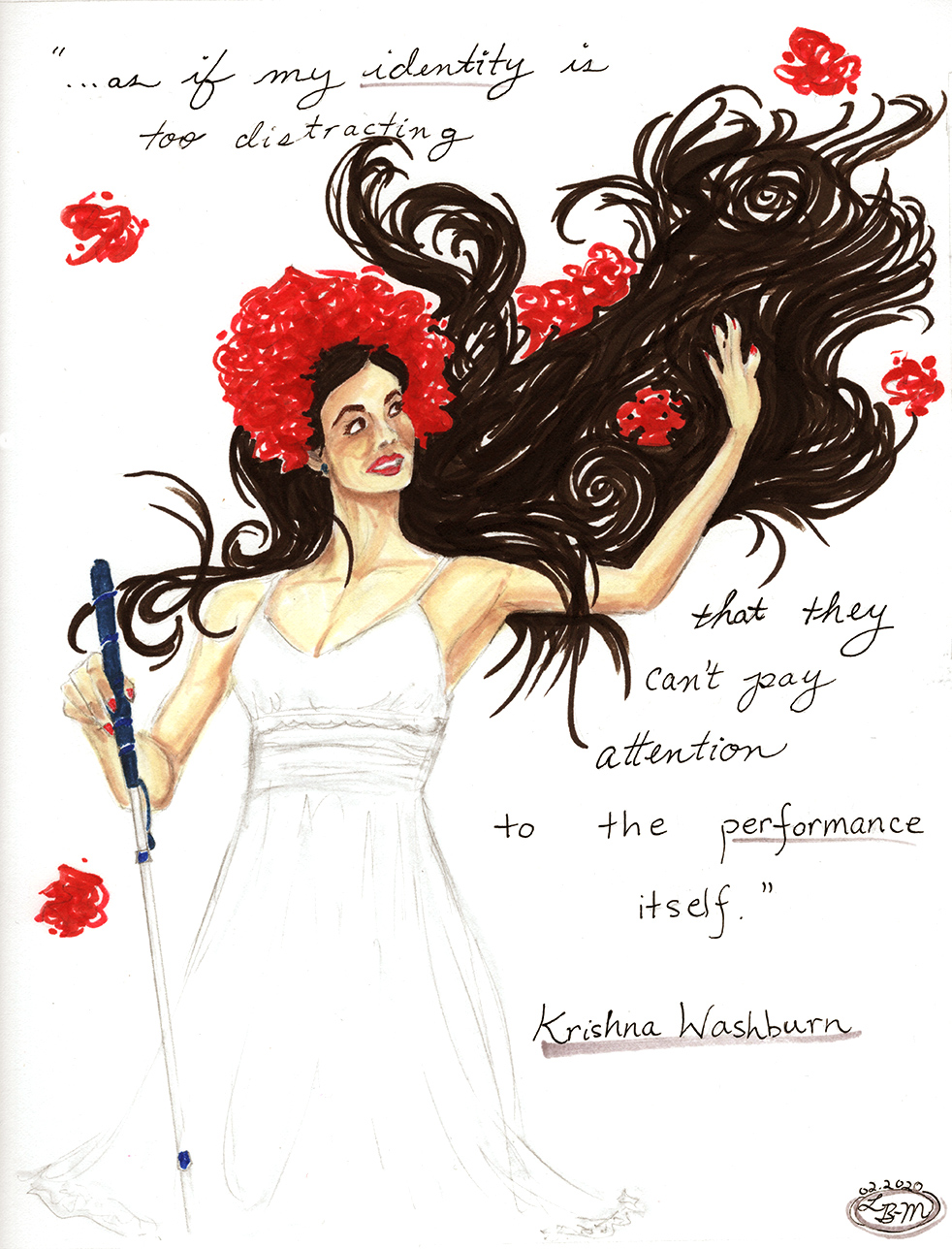

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Krishna Christine Washburn has performed with many dance companies including Infinity Dance Theater, jill sigman/thinkdance, Heidi Latsky Dance, marked dance project, and LEIMAY. She has collaborated with several independent choreographers, including Patrice Miller, iele paloumpis, Perel, Vangeline, Micaela Mamede, Apollonia Holzer and, most notably, with A I Merino, who created Krishna’s signature role as Elizabeth Bathory in Erzsébet. She boasts myriad ongoing artistic collaborations, including work with wearables artist Ntilit (Natalia Roumelioti). Krishna is the artistic director of The Dark Room, a multi-disciplinary project with fellow visually impaired dancer Kayla Hamilton.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

Image description: Krishna is pictured in a white slip dress facing the front, her head inclined toward her left shoulder and arm. She is holding a white cane in her right hand and her left hand and arm are extended to the side. She is illustrated with long brown hair sweeping above her head, adorned with red ornamentation. The quote, “…as if my identity is too distracting that they can’t pay attention to the performance itself” is above and to the left of her.

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

I started dancing as a sighted child at age three. I studied ballet through the Royal Academy of Dance. I was accepted to Barnard College at age 18 and was in a preprofessional dance track. By the end of my first year, I experienced rapid dramatic vision loss. I stopped dancing for a long time. I missed dance a lot, but I didn’t have any life skills; I didn’t know how to walk or open a door. I was helpless for a long time. Seven years ago, I felt like I had regained confidence enough to study dance again, and I’ve been working professionally for five years now.

I have been a principal dancer with Infinity Dance Theater and jill sigman/thinkdance. I just did my second leading role as Elizabeth Bathory in A I Merino’s Erzsébet at the New York Theater Festival Summerfest. I’m also working with other visually impaired dancers and choreographers like Kayla Hamilton. I used to dance for Heidi Latsky, for which people probably know me best because she uses photos of me in promo material. In addition to ballet, I have a considerable background in butoh. I’ve played a lot of ghosts.

I primarily dance in other people’s work, but I’ve done some of my own choreography as well, usually in collaboration. I’ve choreographed for collaborations with a visual artist who does wearable sculpture and with a playwright.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

I take class 365 days a year. I’m one of the only people I know at this point in their career who literally takes class every day. I take mostly ballet class, though I also do a lot of jazz and some contemporary. Most days of the week, I’m also rehearsing in one project or another. I generally have three or four projects going on at any given time. In addition, I am a strong believer in conditioning. I weightlift most days. I also teach athletics to disabled youth; I have a certification as an integrative conditioning coach through the American College of Sports Medicine.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

Though I use a white cane, a lot of people don’t know what a white cane is for. They don’t know that it means I’m blind. I generally have to explain. People who know I’m blind often think that dance is some kind of hobby or cute inspirational thing. No dude, I’m cutthroat; this is my career.

A lot of people assume things about the dancing I must do. They wonder how I know where I am. I am patient and happy to explain the minutia to people if they are asking me those questions in good faith. I’m more patient than most, but it is kind of sad. Most people don’t even know a blind person. They don’t understand what it means to be blind.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

There are two categories of feedback I find problematic. One is: “I couldn’t even tell you are blind/visually impaired,” as if I’m trying to hide it or I’m ashamed of the fact. Why would I be embarrassed? This is who I am, and this is the body I work with. I think they are trying to assure me that they couldn’t tell I have a disability. The other feedback generally comes from people who know ahead of time that they are going to see a blind performer. I think it colors their perception of what they are about to see so strongly that they are not able to see the content of what I’ve done, and instead are fixated on seeing some blind lady dance. It’s almost as if my identity is too distracting that they can’t pay attention to the performance itself.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

I’m only going to speak for blind and visually impaired dancers, but I feel like the educational opportunities available take the worst possible approach. They treat the blind or visually impaired dancer’s body like a marionet and don’t encourage bodily autonomy. In other words, the teacher moves the student around, which basically prevents the student from learning how to dance.

Nobody should ever touch a blind person without saying something first. I don’t know why this is so hard for people to understand. I know a lot of blind people are accustomed to being manhandled, but it’s not the mindset I want serious dance students to cultivate about themselves.

There are certain skills I believe a visually impaired or blind person needs to have prior to studying dance seriously, which are directional hearing, internal balance, and foot sensitivity. I created a workshop called Darkroom Ballet which develops these skills. However, I haven’t gotten to teach it to many blind people, though I keep trying. I’ve mostly been teaching it to sighted people, which is kind of sad. But if a blind or visually impaired person can cultivate those skills first, they can study any dance technique they want.

I really like when teachers use verbal descriptions. That’s one of the reasons why I’m still in ballet class; I know my terms, so I can listen and comprehend. I feel that the more contemporary tradition of just having dancers follow the teacher or choreographer is very inaccessible. Being able to describe the steps or choreography is vital for visually impaired dancers.

I also like when dance teachers offer their own body for blind students to touch and learn from for more complex shapes and patterns. It’s much more respectful than moving the dancer like a piece of clay.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

Something I like about our disability arts community is that in a way we’re pioneers. We don’t have to replicate the crappy things about dance culture that already exist. We don’t have to encourage dancers to trash themselves physically and ignore their wellbeing. We don’t have to replicate tyrannical choreographers. We have a cleaner slate. I would actually like if non-disabled dance culture would assimilate to us.

With regards to open classes, I sneak into open class every day. My money is the same as anyone else’s. Sometimes I ask the teacher for permission; usually I don’t. If you feel confident enough that you can be in the room and no harm can come to you, do as you want. If somebody treats you wrong, they’re breaking the law.

As for performance venues and festivals, why would they not consider disabled performers and artists for any program? We’re spectacular. We’re talented. We’re creative. We’re coming up with some of the newest and most innovative ideas.

Once I auditioned for a dance company and had a great audition, but the choreographer told me that, while he liked the way I moved, he wasn’t sure if he wanted his company to go in that direction, as if disability is a distraction from his genius. I don’t know what to do about people like that. I don’t want to collaborate with people who aren’t thrilled to collaborate with me.

On the other hand, I sometimes get approached for projects or companies I’m definitely uncomfortable with. I was recently approached by a playwright wanting to make an inspirational semi-autobiographical play about me but with a tragic romance. That’s called fetishism.

What is your preferred term for the field?

I like the term “visually impaired” because it’s like a big tent and it doesn’t ask people to go into the minutia of how much sight they have and thus create a sight hierarchy, which I think is counterproductive. I like “disability arts” because we all have multiple artistic skills, whether it’s dance, music, acting, writing, or visual arts. As for me personally, I call myself “blind lady” or “blind lady dancer.”

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

I feel like it is improving in certain ways. Alice Sheppard won a Bessie award, and that was one of the greatest things that ever happened. I want to be Alice when I grow up. However, while the disability arts community is becoming bigger and more exciting within it, getting non-disabled people to support us is still challenging.

For example, in order for me to be safe in my performance space, I need a little time in the space before tech rehearsals. That’s just basic. If I can’t learn the dimensions and feel the floor texture, I can’t perform safely. Sometimes venues don’t understand that. On the phone or over email, they’ll tell me I can’t come in early, but when I appear and I have my cane and am wearing shades, they say, “Oh my god, what can I do for you? Can I guide you around by the arm?” It’s this weird bipolar relationship. On the phone they deny me access, but when they meet me in person, they suddenly feel guilty. It’s very complicated and stressful and puts me in a lot of uncomfortable situations. I was able to get an hour and a half on my stage when I performed last month. I had to work really hard really fast. If I was not as skilled as I am, I wouldn’t be able to pull it off. This scenario happens to me repeatedly.

Any other thoughts?

What I would really love is to just do my work. That’s all I care about. It’s been so difficult for me to acquire the skills I have so that I can work at the level I do. I wouldn’t do this if it wasn’t the most important thing in the universe to me. I’d sacrifice just about anything else. I breathe dance every minute of my life. And I’m a hustler. I take every gig I can get unless I think it is inspiration porn. I’m in class every day. I’m constantly building my skills and talking to people about the art I do. I’m always striving. I work so hard, but some people think I just show up on stage and manifest as a fascinating other-worldly alien creature. No man, I’m a straight up jock hustler. I have a gig every month, and it’s going to be like that until the day I die.

Krishna Washburn, Photo by Jazzmine Beaulieu, taken in relation to Maria, a choreographed drama by Micaela Mamede

Image description: Krishna is pictured standing and facing front with her left foot gently pointed to the side of her. She is holding a white cane to the right of her body and both hands are delicately holding the cane. She is smiling with her face cocked over her left shoulder. Her hair is in a long braid adorned with a white headdress and hanging over her right shoulder. She is wearing a white slip dress.

~~

To learn more about Krishna’s classes for visually imparied dancers, visit darkroomballet.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

One Response to “Krishna Washburn: “I’m Cutthroat; This is My Career””

[…] Originally posted on February 8, 2021 at Stance on DancePlease consider making a donation to support the completion and publishing of the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project! […]

Comments are closed.