Antoine Hunter: “I Move My Body and I Communicate”

BY SILVA LAUKKANEN; EDITED BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Antoine Hunter is an African American Deaf producer, choreographer, dancer, actor, and advocate. He has performed throughout the Bay Area and internationally, and is the founder and director of Urban Jazz Dance. In 2013, he initiated the Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival, the first of its kind. He teaches dance and ASL in both hearing and Deaf communities, and is on faculty at East Bay Center for the Performing Arts, Shawl-Anderson Dance Center, Youth in Arts, and Dance-A-Vision.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

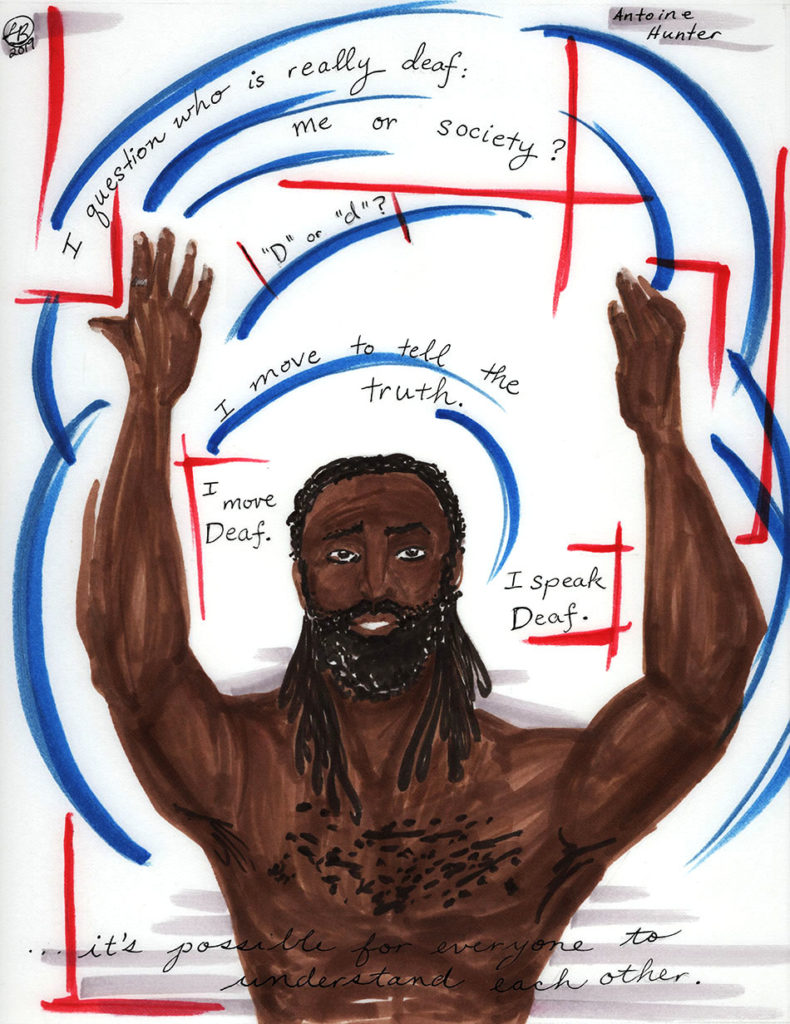

Image description: Antoine is depicted facing front close-up from the chest up. He is shirtless and his arms are raised up above his head. Red and blue lines of energy swirl around him along with the quotes, “I question who is really deaf: me or society? ‘D’ or ‘d’? I move to tell the truth. I move Deaf. I speak Deaf.” and “…it’s possible for everyone to understand each other.”

Image description: Antoine is depicted facing front close-up from the chest up. He is shirtless and his arms are raised up above his head. Red and blue lines of energy swirl around him along with the quotes, “I question who is really deaf: me or society? ‘D’ or ‘d’? I move to tell the truth. I move Deaf. I speak Deaf.” and “…it’s possible for everyone to understand each other.”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

Dance has always been part of me from the day I was born; I have always been moving. Growing up in the Bay Area, especially in Oakland, breakdancing was very popular. But my love of dance started by watching Oakland Ballet Company’s Nutcracker. Being Deaf, when I would watch TV or go to the movies, I couldn’t connect with what I was seeing even though I was watching the same event as everyone around me. I would miss all the jokes. When I saw Oakland Ballet, it was wonderful. No one was talking onstage; instead, everyone was dancing to communicate. It showed me that I can use art and dance to communicate with the world.

However, my mom couldn’t afford to take me to dance lessons, so I had to wait until high school. My high school dance teacher taught modern and jazz and had a lot of energy and fire. Whenever she danced, it was always with passion. She made me want to dance like that too. She didn’t treat me differently even though I was the only Deaf student in her class. She didn’t make me feel like an outcast.

I was so hooked on dance that I wasn’t really thinking about college. My senior year, my dance teacher asked me what my plans were, and I said I had no idea. She urged me to audition for the California Institute of the Arts. That audition class was the bomb. It was the first time I stood in the front of the line, and the first time I was exposed to styles like Horton technique and ballet. I even fell during the audition. I had this serious look on my face, dancing so intently, and then I fell with a big smile. But then I got a letter that I was accepted.

The highlight of my dance life to date is the recognition I’ve received for the Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival. It is hard for the Deaf community to be recognized for our culture, art, and spirit. The festival is bigger than me. I want the Deaf dance community to grow because, if they grow, I grow too. With the Deaf Dance Festival, I basically tried to create a platform for Deaf people. Deaf dance artists have come from 20 different countries to participate, so I changed the name to the Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival.

Participants all say it’s a miraculous experience to work with a Deaf director who knows how to give them what they need and who appreciates their work. A lot of time, Deaf dance artists don’t get what they need. For example, some people who have come to the festival talk about how they’ve had to dance on carpet, which is not ideal for a Deaf dancer. Sometimes they’ve been in situations where the lighting designer decides what to do without their direction. It can be frustrating. When they get here, they’re so inspired to work with a director who understands. They feel welcome, safe, inspired, and respected.

The festival has grown every year. It happens every summer in August. This past year was our sixth year, and we had 53 artists. They come from all over the world, and they bring their own cultures and sign languages.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

I dance seven days a week. I practice ballet, modern, jazz, and African, and I also find ways to incorporate ASL. That’s helped me develop a vocabulary to give both Deaf and hearing audiences a way to enter the work together. I have been working on this for the past 11 years, figuring out the common denominator for everyone to understand each other. I not only dance but am also an actor and write scripts too.

In my choreography, I try to give a sense of what’s happening in the world. For example, most people don’t know a lot about or don’t want to talk about what it’s like to be Deaf in prison. If you’re Deaf and arrested, you might not have access to an interpreter to find out exactly what you’re accused of. In prison, hearing people often have access to telephones, but this isn’t the case if you’re Deaf. Also, prison guards don’t understand how to communicate with Deaf prisoners, and subsequently punish them for insubordination. It’s not an easy thing to talk about, but society needs to know what’s going on.

My most recent show was about Deaf women of color and the #MeToo movement. The cast was 98 percent Deaf women of color. We don’t just dance for entertainment. We also address social justice issues.

I also teach dance in the public schools and at different studios. I go across the country to teach children and adults, as well as teachers how to teach, not only to Deaf students but also to people with unique challenges. I want people to be included. That’s my biggest passion because dance saved my life. In high school, I felt very suicidal because I was isolated. But then I poured myself into dance and that gave me a way to communicate with the world. I want to help pass on those tools.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

Times are changing, and people are beginning to see that Deaf people can dance. But I do remember when people used to say Deaf people couldn’t dance. People would say, “They need to hear the music.” The reality is: We all have hearts. We all have feelings. Art is expression. Music is art. If someone has something to express, we’re going to feel it.

I do feel the vibrations sometimes, but if I’m jumping, I can’t feel them. That’s another stereotype, that we can feel the vibrations. Yes, it’s true we can sometimes feel the vibrations, but if I’m doing a double pirouette, a jump, or a roll, I don’t feel any vibrations. I have to create my own internal music to stay with the timing, and it’s not an easy thing to do. It takes practice and confidence. People assume I have some hearing because I can dance and speak, but I have zero hearing. Sometimes people don’t believe me, so I question who is really Deaf: me or society.

Another stereotype is people assume Deaf people can read lips. If you’re trying to read lips, “m” and “b” look very similar, for example. It’s easy to misunderstand; it’s 95 percent guessing.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

In Deaf culture, many people don’t consider Deafness a disability, though some do. For me, Deaf culture is practically my DNA: I move Deaf, I speak Deaf.

In Deaf culture, the “D” is capitalized. If people don’t know sign language and want to communicate, they should be brave enough to hire an interpreter and not look for an easy way out. They should also understand that when the interpreter speaks, their voice still belongs to the Deaf person. Lots of times, people compliment the interpreter, not the Deaf person.

I think it’s possible for everyone to understand each other. It shouldn’t matter what language we use. I often meet people from different countries, and it doesn’t matter if they can hear or not. I move my body and I communicate. All the different cultures can be adapted through the body.

I don’t mind when people call me inspirational. What I’m trying to do is bring the world together. I grew up segregated and alone, and I don’t want anyone to deal with that. I could have ended my life so many times, but I would have missed all these wonderful opportunities.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

I don’t believe there are enough training opportunities for Deaf people at all. When they come to take my class, they breathe deep like they just came out from being under water. They can finally understand what’s happening in the class because I sign. Even if they don’t know ASL, there is that connection. I feel humble and grateful when I’m teaching. We need more Deaf dance teachers, so I’m currently teaching my dancers how to teach as well.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

I would love to see that! That is one of my big goals, to create more opportunities for Deaf dancers here in the Bay Area. I’m pushing three of my Deaf dancers to teach, choreograph, and produce. There are so many dancers who come up to me and say, “Hey I want to join a dance company.” Deaf dancers feel like they can’t go anywhere.

What is your preferred term for the field?

Deaf N’ Dance. I actually wanted to call the festival that to signal that we are both Deaf and we dance. I was knocking on doors to say that we need a festival for Deaf dance artists, but a lot of theaters said, “Who wants to watch Deaf dancers?” Some would say, “I know you can dance, Antoine, but can they?” I was told that I was wasting my time. I will be honest: I almost started to believe it, but I made it happen.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

For a long time, I was the only Deaf dancer around. Now, when I go to a dance studio like Shawl-Anderson in Berkeley, people at the front desk say, “Good morning,” and “Don’t forget to sign in” in sign language. People in general are more willing to write things down and communicate.

Because of the Deaf Dance Festival, I feel like there are many more Deaf dance artists. Last year, there were 53 Deaf dancers and choreographers from all over the world. And after the artists leave, they want to create similar events in their own countries. I’ve helped start events in Turkey, Colombia, and Brazil. I started and hosted the San Diego Deaf Dance Festival, and we donated all the money to San Diego schools with Deaf children. Next year I hope to work with Deaf dancers in Africa.

But when it’s all over, it can still feel lonely. When you have another Deaf person to take dance classes with, it can be a major feeling of gratitude and happiness. I have an amazing assistant who is Deaf, Zahna Simon. She has shared so much with me.

If I see other Deaf people doing their art, I can learn from them. If they grow, I grow. My community is growing.

Pictured: Antoine Hunter, Photo by RJ Muna

Image description: Antoine is dancing alone onstage. He is standing on one bent leg. The other leg and his arms reach across him as his torso leans away.

~~

To learn more about Antoine’s company and work, visit www.realurbanjazzdance.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

One Response to “Antoine Hunter: “I Move My Body and I Communicate””

Hugs Antoine. So glad to see you continue your brilliant work!

Comments are closed.