Arguing for Equity through Quantitative Research

An Interview with Elizabeth Yntema and Isabelle Vail at the Dance Data Project®

Dance Data Project® is a nonprofit that promotes gender equity in classical ballet through data analysis, advocacy, and programming. It was founded in 2015 by Elizabeth Yntema as an independent project to address the gender disparity she witnessed at the most lucrative level of the dance world – top ballet companies. Isabelle Vail joined Dance Data Project® in 2017 and now serves as its director of research and development. Here, Elizabeth and Isabelle discuss why assessing ballet companies’ gender inequity through data analysis is key to addressing the issue and changing the field.

Lawrence Rines, Chisako Oga and Derek Dunn perform Helen Pickett’s Petal during Boston Ballet’s BB@Home: ChoreograpHER, an initiative supported by Elizabeth Yntema. Photo by Liza Voll, courtesy of Boston Ballet

~~

How did Dance Data Project® begin?

Elizabeth: I had been involved in a lot of different charity and philanthropy work in Chicago and was successful in raising money for different causes. I eventually joined the board of Hubbard Street Dance and ran their gala before moving over to the board at Joffrey Ballet and running their gala. I began to question raising money for all-male productions. It wasn’t just male choreographers and artistic directors; I wouldn’t see any set, lighting or costume designers who were female. I started to ask questions about why there aren’t more women choreographers. I wasn’t getting any good reasons, but I was hearing inconsistent rationales like, “This isn’t really a problem because the company was started by a woman,” even though that woman departed this earth 30 or 40 years ago. I started doing research and found some reporting on the problem at the NY Times and NPR, but nothing consistent. Amy Seiwert, who until recently was the artistic director of Sacramento Ballet, looked at one season’s worth of data, but the work hadn’t been repeated. I realized that if I was going to make the case that there weren’t enough women in leadership positions, I was going to have to start gathering data.

Isabelle: This was back in 2015 when Liza was operating the project from her kitchen table. She and another woman, Susan West, started building a database, looking at mostly prominent ballet companies around the world on a platform called Airtable, which is an interactive database. They were taking down the names of works being programmed and linking them to different companies and choreographers.

I came on to Dance Data Project (DDP) as an intern to help clean up that database. We realized we needed to condense the data into reports. Simultaneously, Liza was getting DDP incorporated as a 501c3 nonprofit. When we became a nonprofit in 2019, we realized we needed to zoom into the data and start producing reports on different aspects of the data. We published our first leadership report in 2019.

Elizabeth: As Isabelle was saying, DDP started out simple but what we have been attempting to do is to look at the economy of ballet through different lenses. It’s a very big business. One of the things that impedes critical analysis of this art form is the lack of hard data.

Isabelle, what drew you to this work?

Isabelle: I grew up in very small regional dance schools, so my training was rooted in seeing women in the front of the room and admiring them. I wanted to emulate not only their technique, but also their leadership. When I would go away and train in the summer, the people in charge of the programs were men. I didn’t think much about it when I was young; that’s just how things were.

When I went to college, I started exploring more feministic approaches to ballet and realized there’s a disparity in the industry. When I met Liza, she completely blew my mind. Looking at a database full of male names clarified for me how women were at the front of the room in small regional companies that didn’t have much sway in the dance world, but at huge multi-million dollar ballet institutions, there were few women leaders. As I was realizing this, Liza was simultaneously establishing DDP as a nonprofit, so it became less a research hypothesis and more of a legitimate question that could change the dance world. My awareness grew with the organization until it became something I could no longer ignore.

Can you give an overview of what Dance Data Project® does?

Isabelle: DDP started out by looking at companies and their programming and leadership, and that remains the core part of our research. We publish our annual leadership report, which looks at artistic and executive director pay, as well as our annual programming reports, which take the form of a first-look report based on season announcements, and then we take a look at the whole season in our season overview. That’s produced after the season has happened and more data is available. For example, a company might announce an all-female program at the start of the season but don’t have the choreographers or pieces lined up, so that data is preliminary.

We recently branched out into our first global study, which looks at resident choreographers. We also study dance venues, where we look at the programming at various venues like The Joyce Theater in New York City or The Fox Theatre in Atlanta. We also have reports that look at dance festival leadership and programming as well as ballet company boards of directors and trustees. It’s a very comprehensive look at the industry at this point.

For our leadership and programming reports, we try to focus on the top 50 ballet companies in the US that operate with the largest annual expenses. The reason we have a sample like that is because it’s large enough to determine whether statistical relationships can exist within the variables we’re looking at, like programming, leadership, gender, etc.

The other reason we have that sample is because we’ve determined that the classical ballet industry in the US is an oligopoly. These companies operate with a combined budget of $636 million a year, and the top 10 companies within that sample control $386 million, which is about 61 percent of the total. What you’re looking at is a ton of influence. If you take that sample of the top 50 ballet companies and break it into brackets of companies and operations, it gives us a good feel for the trends in the industry.

Obviously, we’d like to grow to look at an international sample in programming equity and leadership pay, but that’s not possible for us right now. European companies operate on a different model with government funding. The top 50 US companies and their subcategories keep the data very approachable for us at this point. We are, after all, a small startup trying to stay afloat while changing the industry.

Elizabeth: We are quintessential entrepreneurs in that we are creating this as we go. We figure out where there’s a need and try to address it. What we’re getting better at is not just focusing on gender discrimination in dance but creating specific resources to address it.

When I was trying to get a feel for the industry, I started going around to companies, maybe 15 of them, and just listening and observing. Each company feels different; there are happy companies and tense companies and formulistic companies and companies where people are excited each morning. Each has their own flavor. On that listening tour, what I was hearing from several of the female choreographers I spoke with was that they were all so darn busy that they felt like they were missing opportunities in terms of fellowships. Our banner on our homepage is our response to that need so women can find opportunities and stop missing deadlines. It’s a simple and low-cost way to help women artists.

We also have a database of women leaders which in part came out of our study of season overviews. If you know dance history, you know women did start and lead things, so in part to recover that history, we’re building a master list of female founders, artistic directors, and choreographers. We’d hear from male artistic directors, “Well I don’t know any good female choreographers,” and this is how we’re directly addressing that. In addition, they go to the same few female choreographers, so now they can go to our website and look at the hundreds of women choreographers. We’re trying to centralize information and make it more available.

During COVID, we realized Dance/USA was not providing the same information that APAP was, so we tried to take information from several different sources and put together resource lists, as well as publish research on how asymmetrical this pandemic is affecting women. It’s being called the “she-cession.”

We’re planning on publishing a global resource listing of not only the biggest 50 companies in the US but also the biggest 50 or so abroad, and what each of these big ballet companies is doing in response to the pandemic – shutting down, partially shutting down, all-live virtual programming, etc. – because we’re watching the industry morph in front of us. Academics and journalists can visit DDP’s site to find that information on a spreadsheet in one place. It will change obviously, as people make real-world decisions.

I will say that our model of operation has turned out to be prescient; we’re remote, we’re gig-based (Isabelle is my only fulltime person), and we tap into academic resources.

Why does Dance Data Project® focus specifically on ballet? Is it because a lot of the power in dance is consolidated in ballet companies?

Elizabeth: Exactly.

What trends have you seen emerge?

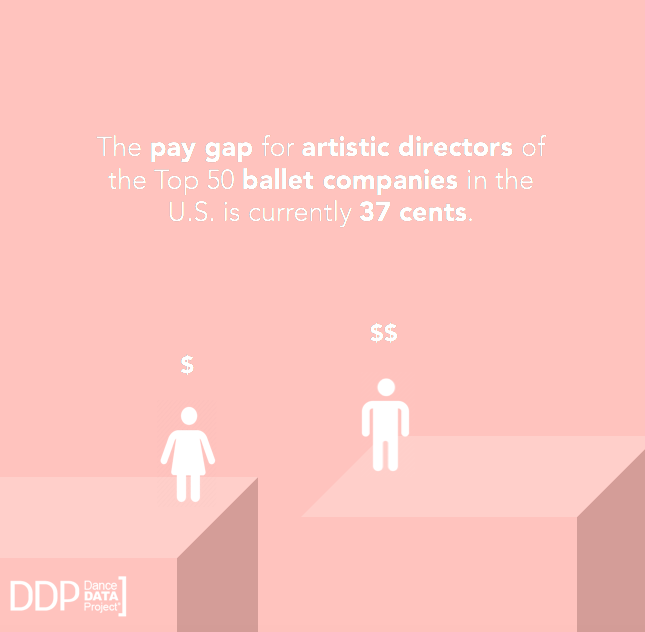

Isabelle: We’ve only been collecting concrete data on this sample since 2019, but last year when we produced our first study, we looked at the three prior years to at least get some feel for the trends. We found that women earned $.62 in 2016 and $.68 in 2017 for every $1 men made as artistic directors of a top 50 US ballet company. In 2018, that figure dropped to $.61. This year, that number went up to $.63. The numbers hang around that range. We also look at executive directors, and the pay gap is not as stark. We have noticed though that in the top 10 US ballet companies, there’s only one female artistic director, and her pay is 75 percent of her male colleagues’ average pay. She earns more than $400,000 less than the highest paid artistic director.

Elizabeth: And this is if a woman can get the job as artistic director in the first place.

Isabelle: The issue with looking at data longitudinally is that we need reliable data, and it’s hard to do that when we’re operating by looking at publicly accessible information. We developed a self-report survey that we sent to the top 50 companies to gauge what their artistic and executive directors’ compensation is, and we’d like to do that going forward to build longitudinal tracking. But at this point, the data is limited in how far back we can look. We’re working on being able to communicate directly with the companies to get long term data.

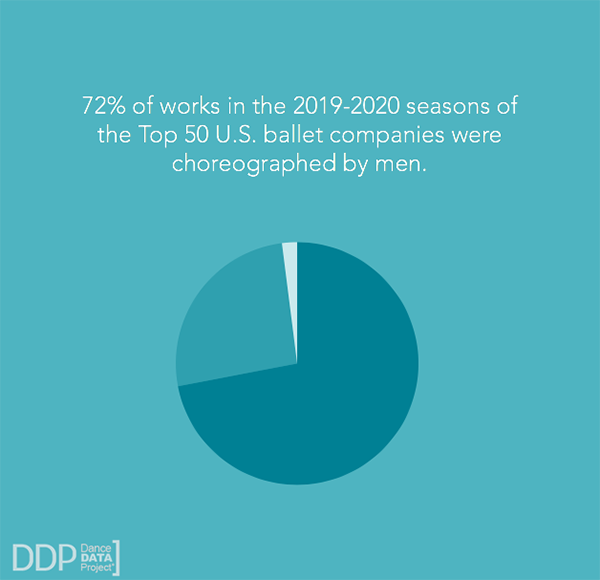

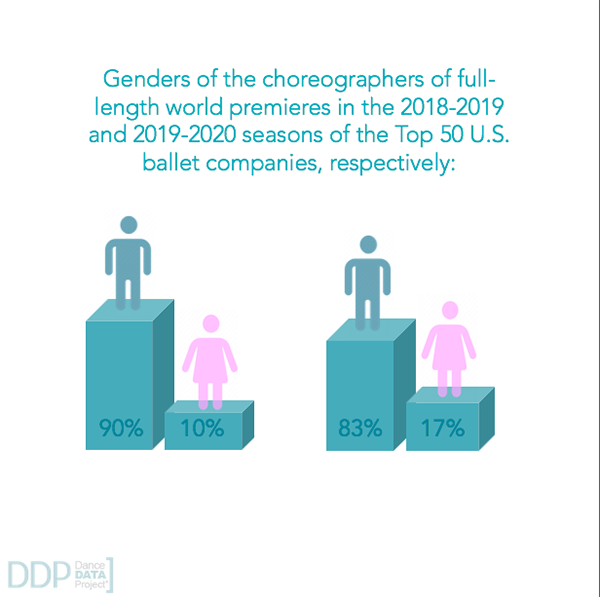

Elizabeth: In terms of programming shifts, we’re seeing that the big world premieres on mainstages are almost exclusively male. If women choreographers make it to the mainstage at all, they will be asked to make a 15 to 20-minute piece as part of a mixed repertoire bill, not a full-length work.

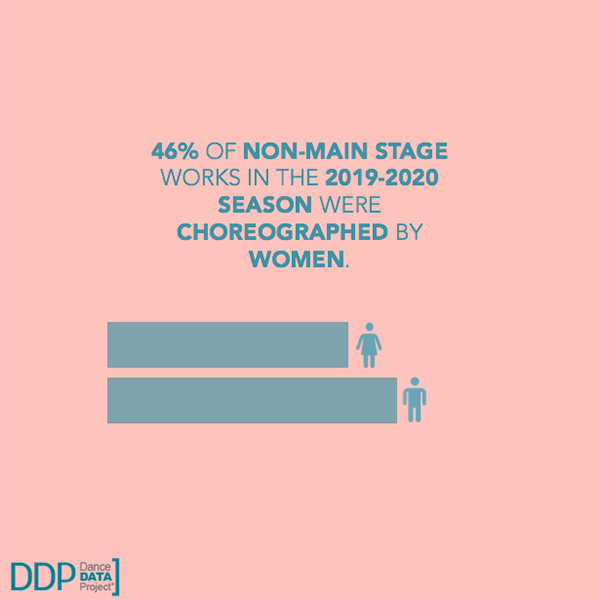

Isabelle: We looked at world premieres and broke them down by full-length versus mixed bill and mainstage versus non-mainstage. What we saw was that things are a lot more equitable within the mixed bill non-mainstage category. We think companies are making their programs more equitable when that program isn’t costing them a lot of money and therefore putting them at risk. When they’re having an in-studio or black box performance, they feel much more comfortable bringing in a woman choreographer or letting their female dancers make pieces. We don’t have the longitudinal data yet, but we’re hoping that mixed bill non-mainstage pieces might expand into money-making full-length premieres on mainstages. But if you look at full-length mainstage world premieres, there were 12 of those this year and only two of them were choreographed by women, and I think one of those was a second company work. If this year is any indication, female choreographers aren’t easily moving beyond mixed bill non-mainstage pieces.

Elizabeth: We’re also looking for repetitive commissions. That’s where the Justin Pecks and Christopher Wheeldons of the world really get their careers to take off. They’re not given one or two commissions; they’re given five or six. This is also why the resident choreographer position is so coveted – it’s guaranteed pay, access to dancers, audience, and rehearsal space, so it takes a lot of the stress out of the itinerant choreographer’s life.

Have you been able to collect any data on people of color?

Isabelle: We recognize that intersectionality exists, but it’s data we’d have to conduct ourselves on a survey rather than going to a website and identifying the dancers of color based on how they look. We would need a certain number of responses to be able to infer about the population of choreographers, leaders, or dancers we were to study, and we’re not “there” yet, in terms of every company getting on board to respond to surveys. For where we’re at right now, operating as a startup with somewhat-limited access to information and reporting on what’s accessible to the public, we can’t reliably source racial demographics. That being said, if you identify as a woman, DDP is going to advocate for you and publish research on you, regardless of race or background.

Elizabeth: There’s a huge amount of sensitivity around the issue. I think that data is important, and I stand by the idea that if you don’t have a baseline and metrics, it’s almost impossible to determine whether there have been advances or not. It’s not in DDP’s purview right now, but if someone did do that work, we certainly would support them. We feel the same way about LGBTQ; while it’s important, it’s not on-mission for us. Since DDP is such a small organization, we really only have the capacity for one focus right now.

At every single level of the dance industry, and specifically in ballet, women are the economic drivers. We’re the ones in the seats, the donors, we pay full tuition for school, we pay for the pointe shoes, the private lessons, etc. And yet, when it comes to the lucrative aspects of the profession, we as the majority are being excluded.

Sexual abuse and harassment are anecdotally a huge problem in ballet. Have you been able to collect any data on that?

Isabelle: Yeah, it’s pretty anecdotal, though I did have a meeting recently with the women of Whistle While You Work, and we were talking about operationalizing their anecdotal research. It’s difficult to turn those qualitative discussions into something that can be measured. Sexual harassment is important to DDP in terms of our advocacy, but in terms of our research, we haven’t even begun to figure out how to touch on it.

Elizabeth: One thing DDP can do in the future is put together reporting protocols and procedures. And given what went on with New York City Ballet in 2019 and the union’s reaction, I’m thinking about doing a month-long social media campaign to encourage women to run for union leadership.

How do you see Dance Data Project® evolving or expanding in the future?

Elizabeth: The sky is the limit; I never thought we’d get as far as we have. That being said, I’d like some funding. External validation is great, but I’m going to continue with or without it. What we’ve found most fruitful are academic partnerships, so we’re going to continue to pursue those.

We’d like to broaden into more global surveys and studies if possible. But there’s so much more to be done just in teasing out how big this industry really is. One thing we’ve gotten a lot of good feedback on is providing resources, something we didn’t foresee when we first started. We’re constantly producing new resources in response to the pandemic and economic dislocation. We’d like to be able to do more of that.

I’d also like to see more long-term study and engagement on how girls are taught ballet, perhaps with an academic element looking at the messaging girls are receiving and how the pedagogy and culture in ballet can be changed.

Isabelle: Liza always said that if we produced the numbers, we’d start to see a huge shift in ballet. We’ve seen some incremental shift, but we now realize how change revolves around deliberate tangible engagement. Since our launch, we’ve gone around to companies and advocated face to face. I think that’s going to drive the change going forward, like producing resources that choreographers and others in the field can use to make it more equitable.

Right now, our priority is really publishing more research, using that research to advocate, and making the change happen ourselves.

What has been the response from top ballet companies when presented with your data?

Elizabeth: It really varies. There are a lot of big companies that are profoundly committed to the status quo in a way that they themselves don’t understand. We don’t pick on any individual company. We show the data in aggregate. We are walking a tightrope; we can’t back down, but direct confrontations aren’t going to go well. Instead, we’re trying to empower the press, audience, donors, and foundations with information and then nudge them to use it.

I’ve branched out and am doing more lecturing on philanthropy, trying to empower women – who will hold two thirds of the wealth in the world by 2040 by many estimates – to ensure change before they sign a check. We’ve been promoting the hashtag #askbeforeyougive. Whether you’re giving $50 or a new wing, ask questions and demand change. Women haven’t felt comfortable doing that in the past. If audiences and donors insist, the companies are going to have to change.

Choreographer Stephanie Martinez, Courtney Shea and Elizabeth Yntema at the premier of Bliss! which Elizabeth and Courtney helped underwrite for the Joffrey Ballet. Photo provided courtesy Elizabeth Yntema.

~~

To learn more, visit dancedataproject.com.