Choreographing Chicana Stories for 30 Years

September 29, 2025

An Interview with CatherineMarie Davalos

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

CatherineMarie Davalos is a Bay Area based choreographer and teacher and the director of Davalos Dance Company, which is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. She looks back on 30 years of making dances about the Chicana experience and how the dance landscape has changed over that time. She also shares the agricultural and culinary inspiration behind her latest piece, Milpa Season.

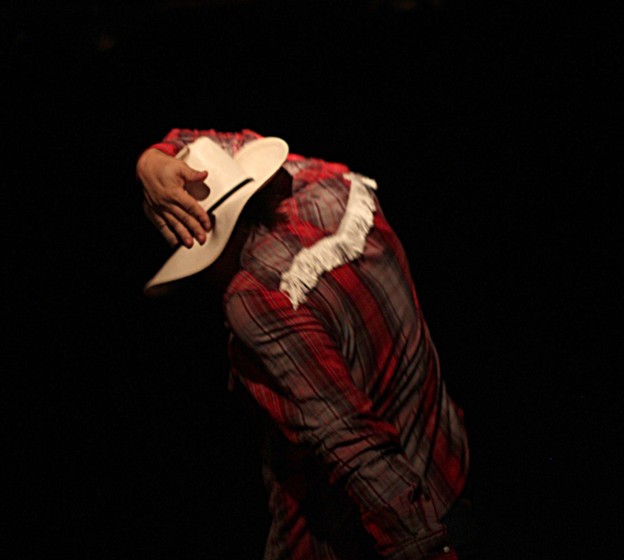

Micah Sallid in The Sacred, Photo by David Gaylord

~~

What is your background in dance? What shaped you as a dance artist?

I did not grow up taking dance like a lot of my company members did. I grew up in a Mexican neighborhood in Southern California. My mom put me in ballet around age five because I was klutzy and couldn’t sit still. I hated it, so she tried other things, like gymnastics. My mom carefully catalogued our lives because she was a librarian. She wrote in my “baby” book, which I read this summer, that I was making dances to music as long as she could remember. That was my thing. I remember staging them in the garage and making my cousins and siblings do parts, speaking or dancing.

When I went to high school, I did song leading, though I think it’s called dance team now. That was the place I could move and there was no cost except for the uniform. When I went to college, I wanted to keep moving, so I took a jazz class, and then a ballet class, and then a modern class. That third semester when I took the modern class, I said, “Oh, this is what my body loves doing. This is what I am meant to be doing.”

My teacher was Mary Jane Eisenberg, may she rest in peace. She passed away about a year ago. She was phenomenal. She was from the Louis Falco Company. Her class was very percussive and physical. I remember that I could latch onto that movement. I took a Cunningham class the next semester when I auditioned for the Cal State Long Beach dance program. There was nothing about it that made sense to my body. My professors told me I should not be a dancer. One teacher said I was too short, too brown-skinned, and overweight. I just didn’t have the body they thought I should have. I was put on probation.

When I went home, I was crying. My dad said, “Are you going to let them tell you that you can’t be a dancer? This is what you want to do. Go back and do what you want to do.” It was like a mental thing, and the next day, I was able to understand how Cunningham worked. I went on to be their number one graduate as an undergrad and then their number one graduate as a grad student.

Something happened with my dad’s encouragement. We grew up in a dancing family. At Mexican family parties, we put on music after dinner, and everyone dances. My dad was my first dance teacher.

Rogelio Lopez in Return, Photo by Yvonne Porta

Why did you start Davalos Dance Company 30 years ago?

I started choreographing because there was no platform for my own experience. There were very few companies in LA. I auditioned for Mary Jane, and she put me in a couple pieces. I loved dancing for her, but they didn’t speak to my lived experience. I started making dances about what it meant to be Chicana. My dad has a PhD. We’re not an immigrant family. We had privilege and education. My mom is Italian, so there was sometimes this discomfort with people not recognizing she was my mom because I’m dark and she’s pale. I wanted to make dances about my experience.

My mentor in college, Tryntje Shapli, said one day after choreography class, “It’s quite an honor to watch you work the same way I do, but you should make dances using your own voice. What is it that you want to say?” She prompted me to start discovering who I was in my body. I started making dances about my Mexican experience in 1994.

This way of working has a lot of cache now. Did you find in the 90s that people were responsive to what you were doing?

Jennifer Fisher wrote my first positive review, and it was the first time a critic understood the metaphor I was playing with about immigration and crossing borders. But at the time I didn’t have any interlocutors. I don’t recall anyone else in LA who was Chicano or Mexican onstage unless they were doing folklorico. I moved to the Bay Area 28 years ago and felt the same way. Now, there’s a whole generation of folks doing Chicana/e/o choreography.

It’s interesting because when I applied for grants for my 30th anniversary show, no one gave me a grant. Pre-COVID, I got grants. What I’m saying right now, for some reason, people don’t want to fund, which I find fascinating and disappointing. I know grants are looking for people of color and want to fund work that asks questions about the world we live in.

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

It’s evolved over the 30 years from typical modern dance set to abstract music, then to modern dance set to Latin music, and now to dance theater set to spoken word, either that I wrote or using poetry that speaks to me. Dance theater is where I landed about halfway through the past 30 years. I wanted the audience members who are not Mexican to understand my choreography, so I started using my voice to share the experience. I often use subtle humor and poetic language with metaphor.

Shaunna Vella in Queen/Goddess/Bruja, Photo by David Gaylord

I travelled to Oaxaca to study Indigenous practices and have since learned it’s not about copying Indigenous dance steps; it’s about coming from a place of authenticity and whole body experience. I now come to rehearsals with a more intuitive way of working rather than a strict plan. Now the dancers generate movement from their authentic places. Over the past 10 years, I’ve started working in this more collaborative space. That feels really good, to see the dancer work through an idea. I’m excited about what each dancer brings to the work and how I can keep making new dances this way instead of using the same formula.

I got a taste of using live music when we were performing in Italy in 2016 and 2018, and I realized I never wanted to go back to recorded music. So since then, I find the funding to hire musicians and a composer.

How have you seen the dance landscape change over the past 30 years, especially with regards to choreographing through a Chicana lens?

I see how Ballet Hispanico in New York brings in female choreographers more regularly. And Liz Boubion started getting us together with FLACC (Festival of Latin American Contemporary Choreographers) 12 years ago. FLACC has been a phenomenal platform for all of us across the country, and during COVID, around the globe.

It’s been healthy for my colleagues who are white to see that they do have a cultural reference and can make dances from their cultural background. I think their dances got better when they started making dances about their own lived experience.

The Chicana feminists started their movement in the 1970s to understand our individuality and our intersectionality. Now everybody wants to do that. But there was no platform for women and women of color at the time.

Shaunna Vella in Queen/Goddess/Bruja, Photo by David Gaylord

What are you planning for your upcoming 30th anniversary shows?

I got excited about tres hermanas after rereading Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Kimmerer. Tres hermanas are growing corn, beans, and squash together. This intercropping system is beneficial for the soil and for the plants. Corn depletes the soil, but if you plant it with beans, then the nitrogen in the soil is replaced by the beans. And if you plant corn and beans with squash, the soil is shaded by the squash leaves, so the water stays in the soil longer.

When I went to Oaxaca this last time, I learned about the milpa season. The Oaxacans plant with the milpa season, where tres hermanas are planted alongside other crops that grow in the climate. It’s based on the rainfall and the way the seasons change. In Oaxaca, the milpa season includes chocolate and chile. I was introduced to a chef, Olga Cabrera, who owns a restaurant called Tierra del Sol. She goes to Indigenous organic farmers and uses whatever they are growing to create her menu. When I was there, she started the meal with chiles. Then it went into a dish based on tres hermanas, followed by chocolate.

Her food is so pure and so delicious, it inspired me. So in my newest work, Milpa Season, the first section is a tap and percussion dance about chiles. Then the second section is about tres hermanas. And the third section is called The Sacred and it’s a love letter to chocolate.

Milpa Season is the second half of the 30th anniversary show. The first half starts with a fashion show that is a retrospective of my work. I have dancers wearing costumes from shows over the years walking the runway. I have two solos that are seminal to my reputation that will also be performed. The first is called Return. That put me on the map as a choreographer. That will be performed by Rogelio Lopez.

The other solo will be performed by Shaunna Vella, who was my first muse in the Bay Area when I met her 26 years ago at Saint Mary’s College. I got to train her for four years in my modern dance classes, and then she performed in my work. It was like she could read my mind and move like me. So I made a solo for her called Queen/Goddess/ Bruja.

I’m going to do a little dance theater solo called Chicana Daughter that I created in 2019 but never got any stage time because COVID hit. It’s about my experience growing up in a Mexican neighborhood and then moving to a white neighborhood.

Micah Sallid, Nina Palada and Catalina O’Connor in The Sacred, Photo by Yvonne Porta

Do you have any sense of what’s next for you beyond the show?

When I choreographed The Sacred in 2021, I invited a folklorico dancer and an Indigenous dancer to be in the work, and they performed both modern dance and their cultural dances. I really love having all that representation on stage. I think my new direction will be bringing artists who are experts in other movement forms that speak to a shared Chicana experience.

I’m also really inspired by the milpa season and feel like I could keep going and make a whole evening length work about it. I would love to perform in Oaxaca and invite Olga to create a dinner to go with it!

~~

To learn more about CatherineMarie’s work, visit davalosdance.wixsite.com.

Davalos Dance Company’s 30th anniversary concert will be held at ODC Theater in San Francisco on October 3 and 4. Learn more here.