The Beauty of Difference

September 8, 2025

An Interview with Tamar Rogoff

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; PHOTOS BY HARVEY WANG

Tamar Rogoff is a choreographer and filmmaker based in New York City. She is known for using a method called Body Scripting, which asks the dancer to follow a script of places in the body. This investigation brings a heightened sense of presence to performance. Tamar’s upcoming piece, Drop Dead…Gorgeous, is grown out of the beauty industry’s target of young people with creams, products, and surgeries that promise a better life. The show investigates our culture’s voracious, unrequited appetite for being thinner, looking younger, and cosmetically more gorgeous, shedding light on the many forms of body dysmorphia and showcasing how so many of us hold toxic judgments about ourselves and others.

Drop Dead….Gorgeous premiers October 17th at La Mama in New York City.

~~

Can you share a little about your dance history?

I studied with the greats. My mother brought me to Martha Graham’s studio when I was about 11. I looked mature, so they put me in the adult class. I got to study with Martha herself. By the time I was 15, I was in the company class. I was a real go-getter. I went to the High School of Performing Arts, which was the “fame” school. I think that was the end of the dream where a child dances in the living room with no sense of censorship. I studied with Martha Graham, Alvin Ailey, and Anna Sokolow. It was such an amazing history, but during my adolescent period, I went from stick skinny to curvy. I got a red ring around my grade in modern dance because I was told to lose weight. As I get older, I realize how formative it is for a child to think, “This isn’t a good body to dance in.”

I went to India and became an Indian classical dancer to wipe the slate clean. Of course, Indian classical dance is very codified, but I happened to have the perfect body for it, because they liked us a little rounder and my flat feet were good for stomping. I realized how cultural difference worked. I was there for three years and did a lot of performing of Bharata Natyam. It widened my perspective. In India there are more than 300 holidays in the year. They are all about telling stories and myths, which was influential when I started site work. My love for storytelling came out of ballet, Martha Graham, and Indian classical dance.

When I came back to New York, something had changed in the dance world. It was the beginning of people like Simone Forti doing naturalistic and pedestrian movement. People were relaxing in their bodies. It was a new orientation, but I missed the whole transition. My work has always been different from what people are doing at the time.

My father was a rheumatologist. From the moment I was born, I was watching people come to his home office using wheelchairs and crutches, so I’ve never understood life without seeing disability. The patients would sit on the couch, and I would dance for them while they waited for their cortisone shots. I had an easy relationship with disability. My father’s practice was very humane; he would hold people’s hands while he examined them so he could make contact. He was always doing things like attaching paint brushes so patients could paint. He was ahead of his time.

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

I begin with an image that won’t leave my mind. I have a story to tell, and I will tell it in whatever way makes sense. I might use a real doctor who has never been onstage partnering a ballerina. My casts are varied, often from the dance world, but sometimes a mix and match. When I did a piece on the holocaust and my family’s history, it was essential to me that actual survivors were in the piece. You might see autobiography in my work. I believe in intimacy. I’ve done a few pieces I call bed pieces where 25 people sit around a bed. There is that close-up personal feeling. Many times, I work with people who might be turned away from on the street, so they can be turned toward with a great deal of empathy because of what people see and learn in the performance. I bring people closer who wouldn’t ordinarily have that opportunity. You never know what you’ll see in my performances.

Tamar Rogoff, Photo by Harvey Wang

You developed a practice called Body Scripting in your work. What is Body Scripting?

I redefine it every day but basically it’s a three-step process. First, you identity a place or space in the body, like the sternum or between the thumb and the tip of the nose. It could even be the space between your chin and the piano in the room. You focus with all your might on that place. And then investigate it. That’s it. If you were focusing on the sternum, you would go into an investigation, almost a conversation, between you and your sternum. You might notice as you move it how it resonates. It gives rise to other movements. It’s like a deconstruction of a dance vocabulary.

The reason it’s wonderful to use with people with disabilities is because the concentration and focus gives a resource for balance. Each dancer has a script. In some part of the process, it becomes improvisational because they have to do the investigation. It’s choreographed and set, but alive and in the moment as well.

How did you come up with Body Scripting?

I had a teacher, Alan Wayne, who worked with ballet dancers with injuries and in rehab. When I came back from India, I started studying with Alan, and it was the first time in my life that anyone mentioned below the skin in dance. No one had ever said, “Drop your clavicles.” Life has changed and in ballet classes now there is more anatomical direction, but not when I was young. You either copied the step or couldn’t do it. I was fascinated by the fact that I had a clavicle. Alan never taught anything like Body Scripting, it was all for alignment and correction, but that’s where I started.

Is there anything else you want to share about your career before we talk about your upcoming show?

I created a performance called Diagnosis of a Faun and it was turned into a film called Enter the Faun. It began when I saw this actor Gregg Mozgala in a performance group that included people with disabilities. He was so charismatic he absolutely captured my attention. He has cerebral palsy. He reminded me of a faun. When I talked to him, he said he felt cut off at the waist. I cast him in my piece, Diagnosis of a Faun. I didn’t realize he had no experience partnering with the other dancers. I got a Guggenheim grant and trained him for a year to become a dancer, but not in a physical therapy kind of way. It was not medical. It was art. He made incredible progress toward being a dancer who could lift and be lifted. I’ve never worked so intensively on a project.

Enter the Faun got a lot of publicity, including an article in the New York Times. A dance teacher in Spain named Esther Mortes read the article. She has a ballet school in Valencia, Spain. After she read my article, she started a free class for kids with cerebral palsy. Eighteen kids showed up. Everyone left their walkers and wheelchairs outside the door and had an assistant. It’s been going on now for 14 years. I go every summer. Gregg came with me for a few years. It is the most incredible place; the atmosphere is full of joy. I taught them Body Scripting. I have a big box of prompts, and kids would pick out something like a piece of paper with the word bellybutton. And then they would dance it. I want to show them how rich their bodies are, that all bodies are positive. It’s amazing that happened, to have that legacy and the film is wonderful.

What was the impetus behind your upcoming piece Drop Dead….Gorgeous?

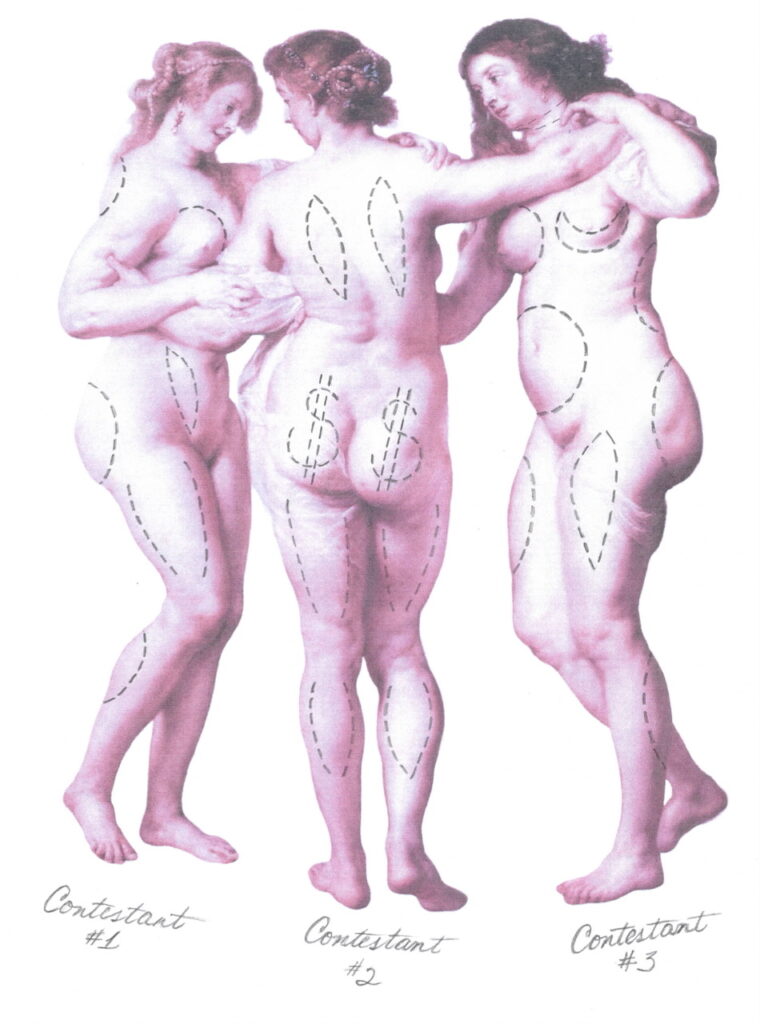

People are starting to realize that we’ve been brainwashed to think we need perfect bodies and no one has one. For years, I looked in the mirror and saw something that was wrong. So many people feel something is wrong with them when they look in the mirror. The beauty industry sells us ways to all look the same, to not look old. They convince us that we can buy the right body.

My piece is a game show where participants can win points to have perfect body parts or turn the clock back. It’s a spoof, but there’s a serious undertone. It’s about how people believe they will find love if they have the perfect body. I have children and grandchildren. It’s hard to watch how this mentality takes over at a certain age. This is my railing against the situation. I’ve cast people in it with different body types. My game master has Tourette’s. I didn’t even know; I just loved him at the audition. He did an amazing piece called The Elephant in Every Room about having Tourette’s and how difficult it is. The game master is very short, but when we see him onstage, he’s gotten taller every year as a perk for being an employee on the game show. He’s on stilts and gets stiffer as he gets taller. Then I have a curvy woman who is a beautiful dancer and a woman in her fourth decade of dancing who is amazing. I also have a 20-year-old ballet dancer who has experienced body dysmorphia and was told she’s not right for ballet. There is a thread running through the piece about the ballet body. It’s about difference; we don’t accept differences. This is looking at how we step off that terrible merry-go-round.

Gerlanda Di Stefano and Gardiner Comfort in Drop Dead…Gorgeous, Photo by Harvey Wang.

What has the choreographic process been? How have you integrated Body Scripting into the process of this piece?

We started with scripts. Everyone got the same script and did it differently. Body Scripting takes away a certain automatic performative aspect. It is very emotional, but it doesn’t start in an emotional place.

I wrote a whole script in words for this piece. I worked with a dramaturg. The game master speaks. I’ve been using Body Scripting with him because he’s an actor, not a dancer, and Body Scripting brings clarity and organizes the body.

Why is this topic important and still relevant?

I think it’s autobiographical. And it’s working – I look in the mirror differently after doing rehearsals. It’s personal for me at this moment in my life to transcend this prejudice in myself, because it goes out to other people.

What a waste of time to spend any time thinking about my body this way when we have so much going on on our planet. Beauty culture is still very much alive in the ballet world and is very dangerous. How are we going to deal with this when all our movie stars are perfect? It’s the right time in the sense that it’s gotten worse because of drugs like Ozempic, though some people need them for medical reasons.

What do you hope audiences take away?

I hope that when they look at my cast during the course of the performance, instead of seeing a dancer who is curvy or old, they see the flow in the bodies and the beauty of difference. Why do we all have to look the same?

~~

To learn more about Tamar’s work, visit tamarrogoff.com.