Creating in the South African Context

An Interview with Lorin Sookool

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Lorin Sookool is a contemporary artist with a dance foundation based in Cape Town, South Africa. In this interview, she shares how her South African experiences and identity are central to her art-making, how she is unraveling her training through exploring improvisation and spirituality, and how her Pina Bausch Fellowship put her on her current trajectory as an artist.

Photo by Tanja Hall

~~

Can you share a little about your dance history – what kinds of performance practices and in what contexts shaped who you are today?

My dance history is inextricably linked to my personal history, which is linked to where I’m from. I was born in 1991 to so-called “coloured” parents just before democracy in South Africa in 1994. I understand “coloured” is a difficult term in the American context, but in the South African context, it’s a racial category that a lot of people are okay with. I was born in a coloured township. After democracy came about, my mother was able to move out of the township to a previously white area, which at the time was becoming quite mixed. I shifted into a new space that was more along the lines of the colonial matrix of power. I went to a semi-private school that introduced me to ballet. From there I got into a studio in the same suburb that offered Graham-style modern dance, acrobatics, gymnastics, tap, jazz – styles from the Euro-American sphere. My dance history is characterized by competition and standardization, philosophies that are embedded in these styles. My entire learning of dance didn’t come from my continent. Over time, my dance trajectory has become about unlearning all that. I’ve now returned to my studies and am working on my master’s degree. I am realizing how much more work is needed to unlearn what was instructed upon me at a time when I didn’t know any better. I come from lines, shapes, smiles on well-strengthened and stretched bodies. The mind and body are quite separate, very performative, and frontal in presentation.

I read on your website that your work “explores complex South African socio-political themes, with a focus on situations of racial, gendered, systemic and institutionalized violence.” Are there one or two pieces from your repertoire that you’d like to share more about?

First, that statement comes from the fact that I believe the body is political. The minute a body steps onto a stage or onto the street, things are signified by our skin, hair, ability. How the body presents itself and what it does are political. I cannot ignore my positionality in my country. I’m defined as coloured, a group of people of mixed ethnic lineages, a form of creolization, and a minority culture. I have chosen to accept that that is how I am showing up in this world and to bring that into my work. Coloured identity politics has formed the basis of a lot of my work.

“Woza Wenties!” at the Liverpool Biennial 2023 at St. Luke’s Bombed Out Church, Photo by Mark McNulty

A piece I would like to mention is The Brunt Blades of Bravado, an eight-minute film that is quite experimental in nature. Moving from personal politics to wider themes within the South African context, one of the stereotypes is that coloured people are reactionary and intrinsically violent. It comes up even in my own social circles. If I say something with a harsh tone, I might hear from someone, “Oh now you’re showing us how coloured you are.” Stereotypes are interesting to me because they appear because of a pattern but are limiting in how we are viewed and how we view ourselves. In 2016 I came across an article called Coloured Bravado by Carvin Goldstone, a well-known South African comedian, in which he writes about an unfortunate situation where one coloured man killed another in broad daylight at a music festival. He described how this issue starts in the playground because the parents encourage the kids to adopt an honor mentality, a very defensive mindset. There was a great response to the article from the public with people saying, “Is this a coloured issue, is this a survival issue?” I loved the comments because they expand beyond race. It’s a situation of people in cramped spaces having to demarcate their area in life and defend it because that’s all they have access to. It’s a lower rung issue that shows up as color, especially in South Africa. It’s an issue of vulnerability and not being able to show your vulnerability as a person struggling to survive.

At the time of creating The Blunt Blades of Bravado, I was six or seven months pregnant, so I worked with the dancer Ilze Williams. We came up with the prison motif and the conversation of the private and public realms. This mentality of defending one’s honor is both in the home and the public space. It is due to a deep-seated lack of faith in governmental support and not feeling supported in this life. That’s the issue, not the racial issue. This is an example of how the personal can connect to a wider issue.

What does your choreographic process generally look like?

While working on The Blunt Blades of Bravado, I started to see myself as a contemporary artist with a foundation in dance, not necessarily as a choreographer and dancer, which in my experience have felt limited within the South African context, though I have discovered that there are more options within those terms in my travels over the years. I began seeing my process as intuitive and emergent in design. If the subject informs the form, then it informs how the work will be presented. Choreography in the sense I had previously understood it took a more minor role, but my work still sits in the space of dance and choreography. It opened what I can do as an artist coming from the field of dance and choreography. With time, my process has become connected to my spirituality. I am a choreographer in the expansive sense of the term – I am interested in plasticity, sculpting, and visual things. The body and its movements are always the beginning and center of my process.

You’re also an MA candidate at the University of Cape Town researching the relationship between decoloniality and improvisational dance practice. Can you share more about this research?

The master’s program is calling for deep questioning and for me to move beyond my own comfort levels. This is what I applied for, precisely because I want to deepen and articulate what I’m doing, but it’s a lot. Decoloniality for me is an ongoing practice that is motivated by a need to question/unmake/dismantle/reinvent longstanding institutions and logics that have been defined by the colonial matrix of power centering Euro approaches. I’m searching for epistemological freedom and a localized perception. Our perception has been colonized. I read somewhere that the issue of Africa is not an issue of chains at our feet but chains on our minds. The success of the colonial project is one of perception.

Academic writers Walter Mignolo and Rolando Vazquez have used the term “aestheSis” – not aesthetics – because aesthetics have already been defined by the modern colonial project. I’m looking for a localized “aestheSis” that centers my own subjectivity so that I can decide my own points of value and scales of evaluation in order to perceive and understand dance making and practice. That is a search.

I realized that a way into this subjective, localized perception is to draw upon my spirituality. This links back to my coloured identity and how that sits within the South African context. The great success of the apartheid system was, through treating coloured people slightly better than Black African people, cause division among us and make coloured people disassociate with their Blackness and therefore their African-ness. Coloured people adopted everything about the white man, including religion. African spirituality is still viewed with suspicion and is either misconstrued or demonized. Part of my spiritual journey has become about accessing technologies related to African spiritualities. This happened during the COVID lockdown. Improvisational dance practice has become an extension of my spiritual practice. Now I’m at the point of exploring ceremony, ritual, beings in liminal spaces, ancestors. It’s something I’m still figuring out in relation to my studies and practice. A part of me wonders: Am I in search of my own post-colonial dance or my own indigeneity after the fact? I don’t have the steps. I have to create them. I’m rediscovering my own Blackness. I didn’t know it would be this epic.

Photo by Bronwen Trupp

You’ve had some international opportunities to showcase your work in the past few years. How have these opportunities informed your work back in South Africa?

There’s a big difference in experiencing an international space as a dancer and as a choreographer. Experiencing an international space as a choreographer only happened last year for me at the Liverpool Biennial, which means I’m still processing it. What I can already say is that my positionality and how my positionality connects to the wider story have become clearer. I know that I do the same thing at home or abroad, and what I prize is home.

The Pina Bausch Fellowship in 2021 was the first time I stepped into improvisation. I was a new mom at the time. My partner for the fellowship, Robert Castello, was in Italy, and we could not work together in-person because of technical issues and loadshedding in South Africa. He said, “Do whatever you want, send me videos, and then let’s have tea and talk.” That was the best thing. He would ask thoughtful questions, like, “What about your face?” I discovered I had a face, and my face was an extension of my body’s expression. My pinky toe was an extension of my body’s expression. I discovered all the cells in my body. I found it so liberating. That is what set me on this current path.

Beyond that, it was quite a successful fellowship. Robert and I worked well in that there was flow and we could bounce off each other. He invited me to Italy to create an improvised performance with a few other improvisers. I want to say that I’ve found that I’m becoming less interested in dance improvisation in terms of its shapes, frames, and cleverness, and more interested in my positionality as a South African femme queer mother. In that process, I took note of the decisions I would make. It pointed to more than the action itself. It’s there that I started to discover what actually moves me. That fellowship was the start of that whole shift. My international experience at once helps me better understand my positionality, therefore uniqueness, but also opens me up to more universal ideas that extend beyond my particularities.

Photo by Philip Grober

I’m also proud of myself for having the courage to choose a partner for the fellowship from a completely opposite perspective: older, white, European, male. Those are the kind of experiences that will stretch me. I’m here talking about what I’m doing partly because of that.

What’s next for you? Do you have an upcoming project or focus you’d like to share more about?

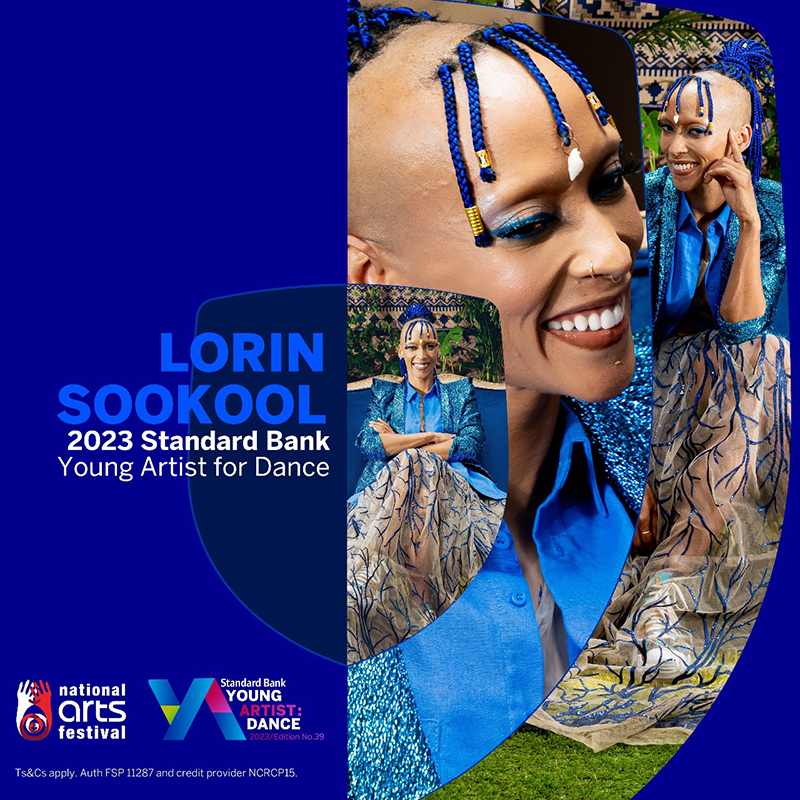

I recently won the Standard Bank Young Artist Award for Dance and will be presenting my next work at the South Africa National Arts Festival this year. I’m excited to receive this recognition at a time when I feel like I can make the most of it. I will be producing a two-pronged offering that sees my practice expand. I will be creating a group work for the first time for my debut performance. The company I’m working with is a multi-racial group, and of course I’m not going to ignore that. I’m going to use improvisation as the mode and tool. I’m excited to put my thinking into practice on other bodies and witness my own growth through them.

Image courtesy Standard Bank Young Artist Award

~~

To learn more about Lorin’s work, visit www.lorinsookool.com.

Read about her Pina Bausch Fellowship here.

Read about her Standard Bank Young Artist Award for Dance here.