Preserving A Piece of Dance History

An Interview with Leslie Streit and Robin McCain

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Leslie Streit and Robin McCain are filmmakers based in San Francisco who recently produced An American Ballet Story, a documentary film about arts philanthropist Rebekah Harkness and her company, the Harkness Ballet. Rebekah Harkness was a dancer, composer, and philanthropist who was active in the 1960s and 70s in New York City – a time of political change and protest for women’s, racial and gay rights. She produced and supported two professional touring companies as well as a youth company and a world-class school during the last 20 years of her life. She also gave financial support to many of the great names in dance, music, and visual art and was a controversial figure in her own time and continues to be even now. Leslie and Robin have brought Rebekah Harkness and the Harkness Ballet to life in An American Ballet Story.

Note: This interview was first published in Stance on Dance’s fall/winter 2023 print issue. To learn more, visit stanceondance.com/print-publication.

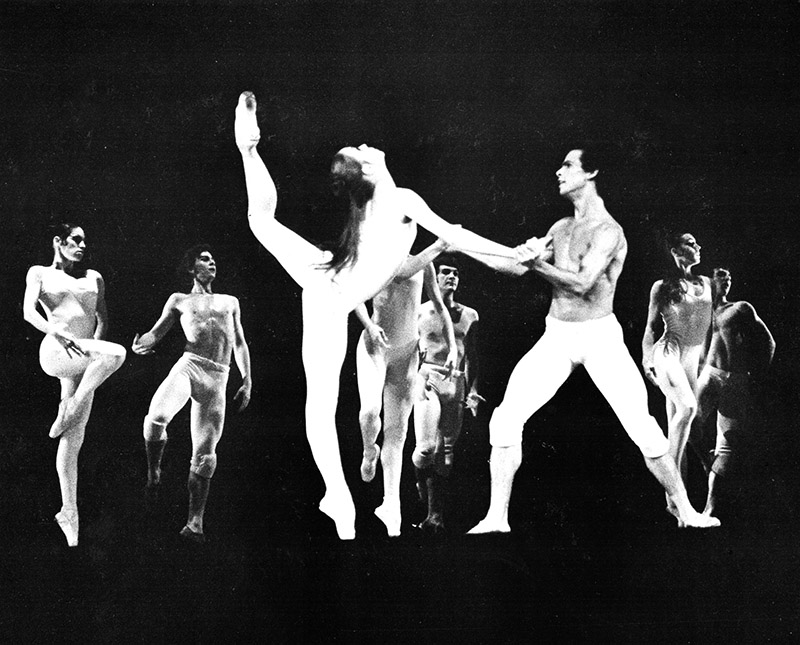

Lone Isaksen and Helgi Tomasson in “Time Out of Mind,” choreography by Brian Macdonald, photo by Michael Avedon for the 1965 Harkness Ballet Souvenir Program, courtesy of the Harkness Foundation for Dance.

~~

What is your history making films and documentaries?

Leslie: In the early 1990s I was teaching jazz dance at a performing arts school and at community colleges around the Bay Area. I was very involved in the arts and dance community. Robin and I started an experimental theater company in a working cannery warehouse where we focused on original shows that featured audience interaction. We built the interior of the theater ourselves in a 1,000 square feet space and worked with dancers, actors, visual artists, and composers from the community to create evening-length site-specific performances. We also began to integrate a variety of short films into our performances to move the narratives forward. At first these were on 8mm film and then we transitioned to shoot on video. Our final show was about vampires in cyberspace, and we had the opportunity to take this show on tour to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. By the time our theater closed in the mid-90s, we had built a sizable collection of interesting short digital films that were broadcast on syndicated television channels starting up at that time across the United States. That’s how we began.

In 2005 we completed our first feature – a narrative/documentary hybrid that played at many international film festivals. Then we went on to a second feature – this time an actual documentary called Elly and Henry, about Holocaust survivors who built the first solar house in America. That film is still in distribution and available on several streaming platforms and DVD.

What was the impetus behind An American Ballet Story?

Leslie: In 2010 we were invited to do a video project at ODC San Francisco documenting a 13-week workshop taught by Maria Vegh. She had been co-director of the Harkness Ballet School in New York City from 1971-1976. Maria kept talking about the Harkness Ballet and we were intrigued. We began the film in 2015 and it took seven years to complete.

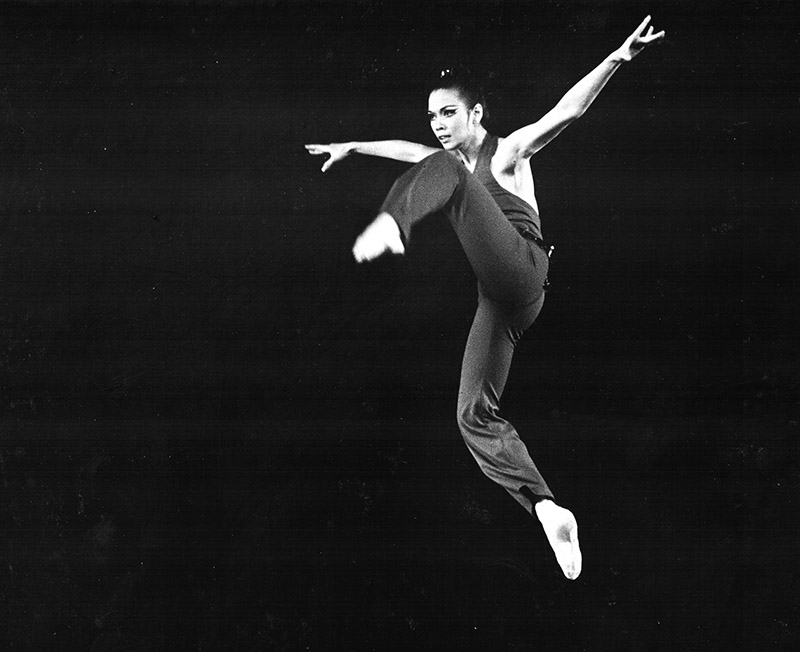

Tina Santos Wahl in “Percussion for Six Women,” choreography by Vicente Nebrada, photo by Milton Oleaga 1972.

What was your process researching and putting together the film?

Robin: We started conducting interviews across the country with very little money. People who had been part of the Harkness Ballet were starting to die and there was no time to waste. We were lucky to acquire 60 interviews during the making of the film. We also spent many days gathering materials at the New York Public Library Performing Arts Archive.

Who was Rebekah Harkness?

Leslie: Rebekah Harkness had grown up as a socialite in St. Louis who did her own thinking. She studied both dance and music composition and began publishing popular songs early in her career. When her second husband William Hale Harkness (a Standard Oil heir) died, she inherited a lot of money which she invested in artists and the arts – particularly dance. Working in New York City, she jumpstarted the careers of Robert Joffrey, Alvin Ailey, Pearl Primus, Jose Greco and also several American visual artists, choreographers, and composers. She supported many things in New York including dance festivals in Central Park and gave opportunities and scholarships to countless dancers and dance students regardless of their race or ethnicity. One of her goals was to create a truly American ballet company and the Harkness Ballet became the first fully integrated major ballet company in New York. Yet she was reviled by some important dance critics and endured endless misogyny, ridicule, and criticism of her personal life and tastes.

I read that she wanted to rename the Joffrey Ballet to the Harkness Ballet, and Robert Joffrey wouldn’t go along with it, so she left and started her own company.

Leslie: Mrs. Harkness took on full support of the Joffrey company from 1962 to 1964 including world tours to Russia, the Middle East, and Europe. Her lawyers urged her to change the name of the company to the Harkness Ballet to reflect her financial sponsorship, but she wanted Joffrey to stay on as artistic director. Joffrey refused and went to the press. So the two companies split. Many of the Joffrey dancers left Joffrey and joined the newly formed Harkness Ballet. Critics and audiences took sides.

Why do you think the Harkness Ballet failed?

Leslie: Ultimately it was money that caused the company to fail. The stock market crashed in 1974 and shares of oil were way down. The barrage of bad press over the years led to the company being denied public funding and Rebekah no longer had enough money to maintain both the company and the school on her own.

Robin: She had also put five or six million dollars (a fortune at the time) into turning an old building into a theater that opened in 1974. It was an old vaudeville theater that she converted and presented to New York City for performances by local and touring dance companies. But it failed and was torn down in 1977.

Why is it important to visit the history of the Harkness Ballet now?

Leslie: As one former Harkness dancer tells us in the film, “She made contemporary dance what it is today. Joffrey was doing stuff and Alvin Ailey was doing stuff, but she put it all together.” The 1960s and 1970s were a glorious moment in the arts – especially in New York City. The Harkness Ballet was a huge part of that. It is a forgotten world. Rebekah Harkness, the company dancers, and choreographers – which included many who set modern, jazz, flamenco, even East Indian style pieces on the company – deserve credit for bringing about a revolution in ballet by catalyzing arts inclusiveness, a city-wide outreach program with free performances, and a ballet school whose teachings were based on kinesiology and scientific research rather than a rote way of learning. She also focused on hiring American dancers, artists, designers, choreographers, and composers, especially at the beginning of their careers. This included women – not only dancers – but choreographers, composers, and designers, which was not typical at that time. All the Harkness company’s work was unique and original. If today’s artists are not aware of the history, meaning, and influence of artworks and art movements that came before them, how will it be possible to build on the past and create new and truly unique work? Many of the freedoms and much of the inclusiveness that artists take for granted today began with the Harkness Ballet.

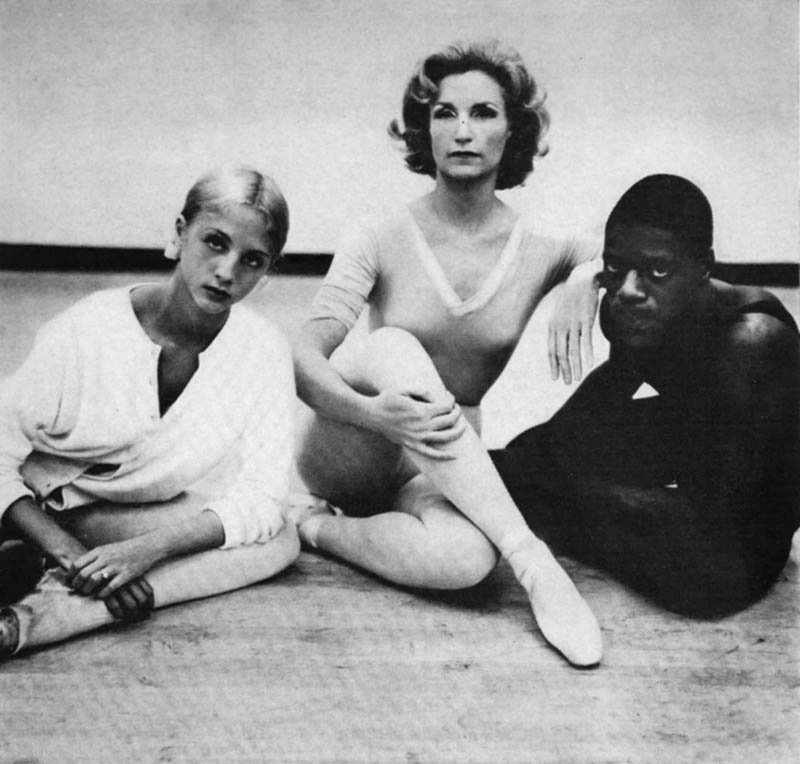

Marjorie Tallchief, Richard Wagner, Dennis Wayne and Finis Jhung in “Ariadne,” choreography by Alvin Ailey, photo by Michael Avedon for the 1965 Harkness Ballet Souvenir Program, courtesy of the Harkness Foundation for Dance.

What do you believe is the Harkness Ballet’s legacy?

Leslie: The Harkness artists themselves were pioneers and went on to become directors, choreographers, and teachers all over the world. The school (which lasted until 1985 – 10 years longer than the company) and its methods of teaching are of course a big part of the legacy. Its influence is seen in dance studios everywhere. Many of the company’s pieces and their musical scores traveled to other companies and some are still being performed today.

Robin: The Harkness Foundation for Dance continues to give generous grants every year to dancers, dance projects, theater programs, and dance organizations in the New York City area, and The Harkness Dance Center continues the spirit of generosity to the NYC dance community. Located at the 92nd Street Y, it offers classes in diverse classical and world dance forms to people of all ages, houses resident companies, screens films, and presents performances. In addition, the Harkness Center for Dance Injuries provides dancers with cutting edge care and continues research and education into injury causes and best therapies.

One way of looking at the story of Harkness Ballet is that Rebekah Harkness was a very rich and powerful woman who wielded her income to make the company she wanted. That system of very wealthy donors dictating the way companies are run continues today. Are there downsides to arts ingenuity relying on a few wealthy individuals?

Robin: In 1962, American funding for the arts was all through private money – ticket sales, patrons, and donors. There was not yet an NEA or access to nonprofit status and public funding. This made it harder to encourage the kind of diversity and inclusion that we associate with public funding today.

Leslie: It may still be true that where your grant money comes from – government or foundation – is reflected in the art you see on stage. But as one former Harkness company member told us: If it were not for corporate and government agencies taking on the support of arts organizations during the 1980s, we should look back on Mrs. Harkness with great appreciation. Another question that’s raised in our movie is if she paid for the art, did she own it? No one knew the answer to that question in the 1960s or 1970s. Things were being figured out by people like Harkness and Joffrey.

Linda Strickler, Rebekah Harkness, Unknown Dancer, Harkness Ballet press photo, photographer unknown, 1966.

What do you hope audiences take away from An American Ballet Story?

Leslie: The story is told by the people who were there. It shows the very human side of a major dance company. It is both a happy and sad film. Many of the people we see on screen passed away at some point during the long time it took to make the film. There is nostalgia, ego, ambition, beautiful dance…an honest and intriguing portrayal of lives lived in an exciting time and place.

Robin: Rebekah Harkness supported dance, music, art, and the school she established until the day she died. Even toward the end she attended auditions and performances and was involved with the students, teachers, and trainees at the school. She truly loved dancers and dance.

Leslie: I hope the film is not just for dance audiences but for everyone.

I understand you’re also working on a short dance film about ghosts. Do you want to share more about that project?

Leslie: This summer we’re taking a break from documentaries to return to our experimental roots. We just filmed a series of short films about ghosts and will present the films as video projections on the walls and ceiling of a gallery in downtown San Francisco in 2024. It is a work in progress and will change and evolve wherever we install it. Who doesn’t like ghosts!?

~~

To learn more about An American Ballet Story or find out where the film is being shown, visit anamericanballetstory.com or visit their Facebook page.

An American Ballet Story was released on August 8, 2023 by Random Media.