A Multifaceted Dance Journey

An Interview with Willyum LaBeija

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Willyum LaBeija is a dancer currently based in Seattle who has performed in the ballroom scene and more recently in the physical theater scene. The ballroom scene is an underground LGBTQ subculture originated by Black and Latino communities in New York City in which people compete for prizes and status at events known as balls. The culture extends beyond balls to houses, where chosen families of friends form relationships and create households together. Here, Willyum reflects on how the ballroom culture was a positive and safe space for him, especially as someone with a disability. He also shares some highlights from his career, from performing in the US Army’s Morale, Welfare and Recreation Soldier Show, to performing in Chicago’s balls under the Royal House of LaBeija, to more recently exploring clowning as part of the Seattle-based physical theater company UMO Ensemble.

Note: This interview was first published in Stance on Dance’s fall/winter 2023 print issue. To learn more, visit stanceondance.com/print-publication.

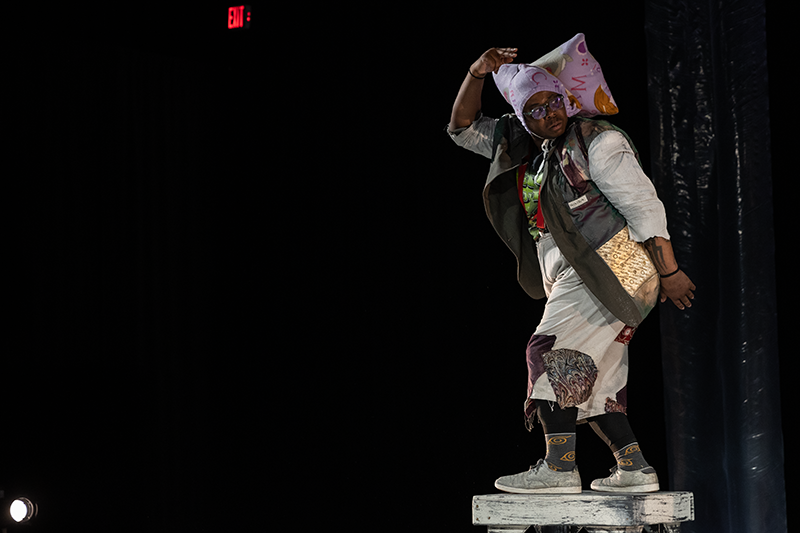

Photo by David Horvitz from UMO Ensemble’s “Squeeze”

~~

How did you get into dance?

I’ve always been a mover. Growing up in Tar Heel, North Carolina, I loved entertainment, and I picked up moves from music videos. In high school, I was a cheerleader and did color guard, honor guard, and March DCI [Drum Corps International]. I did dance performances and competitions as well.

I understand you served in the US Army and participated in the Morale, Welfare and Recreation (MWR) Soldier Show for two years as a dance captain. Can you share more about that experience?

I enlisted in the National Guard in October 2005 right before graduating from high school. I was on special orders, so I was active-duty National Guard working primarily in funeral details and general’s orders.

I actually played for the army band for four years. For the MWR show, there’s an audition process, as well as aptitude tests and things like that. It’s a singing show that’s meant to boost morale and bring up energy. That’s how I got involved. It was during my first two years in the military when I was serving in the 440th Army Band located in Raleigh, North Carolina.

It was an amazing experience. In general, I’ve never tried to hide myself or be someone who I’m not. I feel like I’m a unicorn; I’m unique. That makes me the individual that I am. In the MWR show, I felt like I was around like-minded individuals and peers. We performed contemporary, modern, and majorette, though voguing and the ballroom scene has always been my outlet and my getaway. It was something I did whenever I had dark thoughts. It saved me from doing things to myself I didn’t want to do. I wasn’t voguing in the army, but I was learning and getting involved in the culture. This was during “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

So how did you get into vogueing?

In high school, I started watching voguing on YouTube. My best friend and I would sit in front of the desktop after school, and we’d have a go at it. Growing up, dancing was something I was always known for or just entertaining in general. It was something that helped keep me occupied and keep my demons away.

In 2011 I became part of the Royal House of LaBeija. I relocated to Rhode Island and did a fundraiser for Sojourner House to bring awareness about Domestic Violence Awareness Month in October. My intention for my birthday that year was to be of service to an organization that many do not know exists and to help as much as I can. The Sojourner House provides resources such as housing assistance, shelter, and food for women and children who may have experienced trauma.

I met Derrick LaBeija the night of my fundraiser after I performed. We immediately bonded over the fact that we have the same birthday month. His birthday was three days after mine. He immediately just saw me for me. He took me under his wing and if it was not for Derrick and others, I definitely would not be the person I am today.

How would you describe voguing and the ballroom scene to someone who is unfamiliar with it?

It’s a celebration where anyone of any community is welcome to gather and carry. Yes, it’s a battle, but it’s one where we can lift each other up and be a family, whatever house affiliation you may be. It’s not always about the drama that you see or hear on TV.

Can you share more about the house system and how it works?

There are people involved in a house by association, and then there’s a house representative like the overall father, mother, prince, or princess who sees what you can offer to the house and what the house can offer you in return. The house offers growth. After you’re asked to be part of a house, you go through an induction and learn the history and culture of a house and where it’s derived from. It’s all about being able to take as well as give. It’s a whole family. It’s about what they give you, and you have to be able to give back in return.

What does it mean to you to be part of the Royal House of LaBeija?

I am honored and have always had the utmost respect when it comes to the house. I have been a historian of the house in the past and did a few projects to teach about the history of the house and how it was started. I always treat it with the utmost respect and give it my all.

I moved to Seattle from Chicago two years ago and there are no LaBeijas here that I’m aware of, or if they are here, they’re not active. In Chicago, there were other LaBeijas I got to know who I learned a lot of history from and who were active in the 70s and 80s. Though they weren’t active when I was living there, I had their support. In the Pacific Northwest, the ballroom scene is still fresh. There’s a kiki scene [a less competitive version of the mainstream ballroom scene] and the mainstream scene is slowly growing. It’s definitely a little isolated. On the East Coast, I could drive between cities easily to rehearse and go to balls. Being in Seattle by myself, I’ve lost that motivation to stay as active in the ballroom scene. It’s difficult but I still have the support from my house members in other parts of the country. There’s a kiki scene here that gives me a boost and drive and doesn’t make me feel as alone, and that’s good enough for me right now.

How do you adapt vogue to a body with a disability?

I’m a person with an invisible disability. Dancing can easily be too much, so having control and maintaining the stamina that I need to perform are important. I use breathing techniques so I can catch my breath. I also capture my audience with my breathing as if I’m carrying a conversation with them that will immediately cause them to sync their breathing (not in pattern but in tempo) with me. When I receive this response, it immediately gives me clarity that I am engaging my audience. They acknowledge this is a safe space and are allowing themselves to be as vulnerable as I am during the performance.

My disability is something I’ve always hidden. I was considered normal, but I wasn’t being authentic. Now I’ve come full circle. Since I’ve embraced and accepted that my disability is part of me, I feel freer. I don’t seek validation or approval or ask if it’s okay or apologize. In ballroom, confidence and selling the dance is what it’s all about. Now when I dance, I know I’m selling it and serving it and I know I look good.

Do you feel like the vogue scene is open-minded and supportive of people with disabilities?

Voguing and the ballroom scene in general has always been open to anyone and everyone, including those with disabilities. It doesn’t matter the house you’re involved with; it doesn’t matter the color of your skin; it doesn’t matter if you have a disability; you’re there to enjoy that moment and let your hair down. It’s a breath of fresh air to not worry about anything and just think, “Let me live and let me get life.”

How have you seen the ballroom scene evolve?

Cultural appropriation has become bigger as the scene has become more international. The good thing is that third world countries are introducing ballroom and offering a sense of healing, community, and family, especially for those who may not have had that growing up. But the bad thing is that others have taken from us and gotten monetary value from it without giving back. We all start learning somewhere. When I started learning the dances from YouTube, I was appropriating them, but I took time to learn the history.

What does your current dance practice look like?

I’m currently living in Seattle and working with a group called the UMO Ensemble. We just recently opened a physical theater production called Squeeze where I do clowning as well as move on ladders. It was an amazing experience. Clowning was something I wanted to get involved with prior to the pandemic, but that shut down for a few years. To have the opportunity to learn clowning was amazing.

I choreographed a solo in Squeeze, but the full ensemble piece is a collaboration. The script itself was derived from cyphers [freestyle jams where an open circle is created and people take turns dancing in the center]. It took us two years to develop. It’s about being in a tight situation and feeling ashamed when you have to ask for help. In those topics and uncomfortable scenarios, it’s okay to be vulnerable. It’s okay to not be okay.

I also teach acrobatic gymnastics and contortion. My students recently performed a Fosse acro number that’s a little jazzy to let their hair down. I teach ages four to adult, but these students who just performed are 13. It was their first performance ever. I like to build their confidence.

How has your background in the ballroom scene influenced how you approach physical theater and clowning?

I come across as this strong and demanding presence, but it’s actually my defense mechanism. Having a physical theater piece under my belt and performing in it was a great experience because I pushed myself into a more vulnerable space onstage.

Do you have a current or upcoming project you’d like to share more about?

I am working on a project called Trophy at a residency at UCLA’s Dancing Disability Lab. A lot of my work is about healing and uncomfortable topics that we like to mock because we don’t understand. At some point in our lives, we go through something or someone close to us does. Trophy is about taking the experience of being a survivor or victim and going through the journey of what it’s like to mask or tokenize yourself in order to feel accepted and wanted when deep inside you’re really isolated and alone. How do you move on? You have to see the light at the end of the tunnel. You have to love yourself first and tell yourself you are valid and appreciated.

Photo by David Horvitz from UMO Ensemble’s “Squeeze”

~~

Contact Willyum at WillYumLaBeija@icloud.com or follow him on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter.