Spreading the Joy of Swing Dance

An Interview with Caleb Teicher

BY BONNIE EISSNER

Photos by Grace Kathryn Landefeld, provided by The Joyce Theater

Note: This article was first published in Stance on Dance’s fall/winter 2023 print issue. To learn more, visit stanceondance.com/print-publication.

In June, SW!NG OUT, the critically acclaimed presentation of Lindy Hop, directed by Caleb Teicher, returned to The Joyce Theater in New York City following a national tour. Part performance, part dance party, SW!NG OUT brings the Jazz Age dance into its second century.

Invited by the Joyce to direct a swing dance show in 2019, Teicher, who is nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns, collaborated with renowned Lindy Hoppers Evita Arce, Nathan Bugh, and LaTasha Barnes, as well as bandleader and composer Eyal Vilner—a creative team Teicher dubbed the Braintrust—to conceive SW!NG OUT.

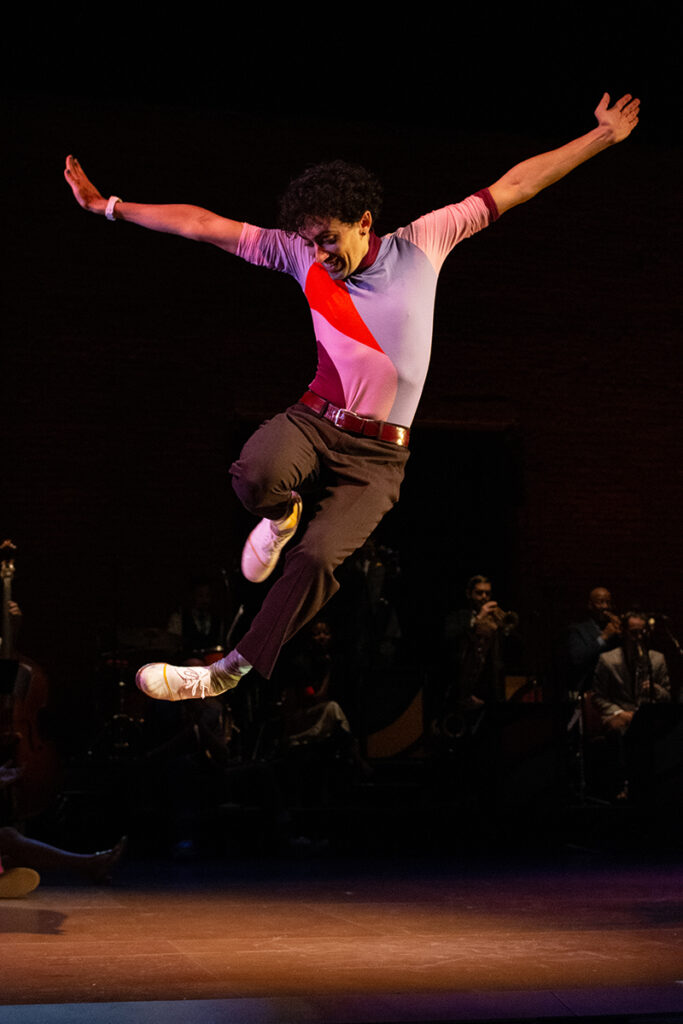

Caleb Teicher in SW!NG OUT

At age 30, Teicher has already won two Bessie Awards for tap and jazz dancing and is known for innovative choreography and performances with diverse musicians, from beatboxer Chris Celiz to the National Symphony Orchestra. SW!NG OUT is Teicher’s ode to Lindy Hop. As the Braintrust members write in a program note, “By assembling genuine, swing-dance superstars in an improvisatory space, this show offers a unique glimpse into their universe: the modern, Lindy Hop scene.”

The first act, called “The Show,” is a mixture of choreographed and improvised dances by the 12 cast members, who include Teicher and the other Braintrust members. The pieces both pay homage to the 1920s Harlem roots of Lindy Hop and offer contemporary twists. Women dance with women or lead men. In one number, Bugh dances solo without music. In another, the dancers create the music through their tapping feet and clapping hands. The show also includes signature routines such as “The Big Apple Contest,” which swing legend Frankie Manning choreographed in the 1930s. The mood is contagiously upbeat. The dancers smile as they swing, and on opening night, the audience whooped and cheered.

In the second act, called “The Jam,” everyone in the audience is invited onto the stage to dance the Lindy Hop as Vilner and his band play and sing. Vilner even hits the dance floor himself.

A week after closing SW!NG OUT, Teicher spoke over Zoom from their home in New York City about the show and their career in tap and swing dance. The following are lightly edited excerpts from that conversation.

~~

When you introduced “The Jam” on the opening night of SW!NG OUT, you mentioned it was your favorite part of the show. Why is that?

The simplest way to put it is that I fell in love with dance, not from watching it. I fell in love with dance from doing it. And I’d say most dancers I know would say their favorite thing about being a dancer is not watching other people do it. It’s experiencing it in their own bodies. Of course, several studies show there’s a psychological connection you make when you watch someone do something and it feels as though you’re experiencing it for yourself. But I do think that having people get up and try swing dancing gives them a better understanding of why people have been doing the Lindy Hop for nearly 100 years, because you just have such a good time.

How does social dance influence either your choreography or your performance of Lindy Hop?

Social dancing is improvisational, and that’s just because you meet someone on the dance floor, you ask them to dance or they ask you to dance, and then you start dancing together. But you don’t have choreography, you don’t have a plan for it. The performance I did for many years incorporated improvisation because tap dance and jazz dance and a lot of the other styles that I was working in have historically incorporated improvisation. But as I started to social dance more, and as I did more Lindy Hop, I became more and more convinced that improvisation was a really valuable aspect of live performance. For many years, I thought, improvisation is what you do when you run out of time to choreograph the whole thing or when you just want to give someone some time to do something. Now so much of the composition of SW!NG OUT is resting on improvisation. And I feel like there’s an ideological or philosophical or artistic motive behind that, which is to say, the reason this show has this palpable energy is because it truly is improvisational.

Why did you create the Braintrust for SW!NG OUT?

The offer to do a big swing show came to me because I had created a lot of concert dance work. The other members of the Braintrust had not made as much concert dance work or had not made as much concert dance work that had been seen on the bigger concert dance stages as I had. I said, I really feel like I’m the right person to direct this and oversee the vision of the show, but for it to have the best impact it can, for it to be the clearest statement on what Lindy Hop is and what Lindy Hop could be, what Lindy Hop will continue to be, it really needs a core team of people who all have either been in Lindy Hop longer than I have or just have a really different perspective on it. So I gathered this group of people with that in mind.

Just to shout out three of them. Nathan is my primary swing dance partner, but Nathan has been swing dancing since the ’90s, since he was in high school. You can’t replace that amount of time. Same for Evita Arce, who also has been in the Lindy Hop scene for over 20 years. And Nathan and Evita have been dance partners, but also have had their own experiences. Evita performed in Swing! The Musical, and she used to run a swing dance company that I was in. And then LaTasha Barnes. Her timeline on Lindy Hop is actually very similar to mine. I think she’s been doing it for about a decade, but her perspective is different because she came from the house dance world, the street dance world, the club dance world. Also her perspective as a Black woman is completely different than mine (for obvious reasons). Lindy Hop is a historically Black dance, and we all dialogue with the tradition of this dance while incorporating our own experiences and perspectives. I felt like, at the intersection of our artistic voices, we would make the best Lindy Hop show there was.

Nathan Bugh and LaTasha Barnes in SW!NG OUT

You’ve said previously that you prefer to follow instead of lead. Why?

It’s more fun for me. As a male-bodied person, when I was first taught to swing dance, the assumption was that I was going to lead. When I started (and this is 12 years ago now), I started leading. And then in 2013, a dear friend of mine encouraged me to switch roles more. There was actually a community group called the Double Troubles where basically the whole idea is that they would put together bits of choreography where everyone led and everyone followed, so you’d switch roles throughout the dance, which at the time was not happening a ton in choreography. It was cool. It was to get better. And I just enjoyed following so much.

I would see people of all genders leading and following, but the conversation is much more forward now, and the mixing of gender expression and dance roles seems even more common. The Lindy Hop community has historically been expansive and accepting, but I would say that Lindy Hop continues to expand.

And then again, to come back to Nathan Bugh. My partnership with Nathan is what really got me more into following because when I danced with Nathan, it wasn’t about gender. It was just about when I danced with Nathan, I felt like I should follow, and I felt like he should lead. And part of that was because of his experience in the dance. And part of that was because it just sort of felt right for our bodies as we moved through space together.

I also should say I’ve come to greater clarity about my gender over the past few years. I always felt not really like a man, but not really like a woman. And then at some point, five or six years ago, I was aware that there was terminology that reflected people who didn’t really feel like one or the other. And at first, I thought, Well, that’s good to know, but I don’t really need to address it publicly. I don’t need to make sure people know how I feel within myself. It’s really just a me-towards-me realization or confirmation. And that made me feel a lot better about myself.

But then maybe three or four years ago, I started to describe myself as nonbinary, and started using gender-neutral pronouns. As I started to allow other people to affirm it by using gender-neutral pronouns, it just made a lot more sense. I think it made a lot more sense for a lot of people who have known me my whole life.

I also should say that I think following as a male-bodied person and also being able to switch roles feels right, because when I meet a person, I kind of just negotiate how it makes sense to dance with them.

What drew you to jazz dance and to Lindy Hop?

My connection to dance is from music. I was that kid who was into ’N Sync and Backstreet Boys, and I danced on my bed and choreographed little routines. I was that kid who grew up watching these pop supergroups and dances on MTV. And the first thing I studied was drums. I loved drumming. I loved playing music. I love music. The first dance form I did was tap dance. I fell in love with tap dance. And that makes sense because tap dance interacts with music in an even more direct way than Lindy Hop. Tap dance is a form of percussive music. So I think the line there goes to other forms of dance that are very much rooted in the connection to music (many of which are part of the African American diaspora), and that’s a lot of social dance. But Lindy Hop particularly has a really strong connection to music, to jazz music, to live music. I also think, as a person who is relatively extroverted, who likes people, that Lindy Hop is a dance about socializing and connecting with people. Lindy Hop is the sort of synergy of two things that really move me as a person. One is music, and the other is connecting with other people.

You mentioned you were invited to curate Lindy Hop classes for beginners at the 92nd Street Y in New York City. Do you think anyone can learn Lindy Hop?

Yeah, for sure. I think there are limits or levels. Not everyone could or should do a split. Not everyone could or should do eight or 10 turns. But I don’t think the point of dancing is to do a split or to do eight or 10 turns. I think the point of dancing is to feel connected to your body and maybe feel connected to someone else or feel connected to the music. What I love about dance is that it has the capacity to mean a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

Caleb Teicher and Joshua Mclean in SW!NG OUT

~~

Caleb Teicher will return to The Joyce Theater in December with their show Bzzz. Described as “a captivating collision of tap dance and beatboxing,” the show will feature a cast of six tap dancers alongside world-champion beatboxers Chris Celiz and Gene Shinozaki.

To learn more, visit www.calebteicher.net.

Bonnie Eissner is the director of communications at The City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center and a writer who covers culture, history, politics, and more. You can see samples of her work at visit linktr.ee/bonnie_writing.