Rethinking Mental Health Access in Dance

An Interview with Stuart Waters

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Stuart Waters is a dancer, teacher, and choreographer based in the UK whose work centers disability and queer perspectives by exploring radical modes of access. In particular, his work focuses on mental health and how building containers for mental health support is part of creating access in performance practices. Here, he discusses his pieces ROCKBOTTOM and A Queer Collision, as well as some of his initiatives to make dance spaces more inclusive and safer.

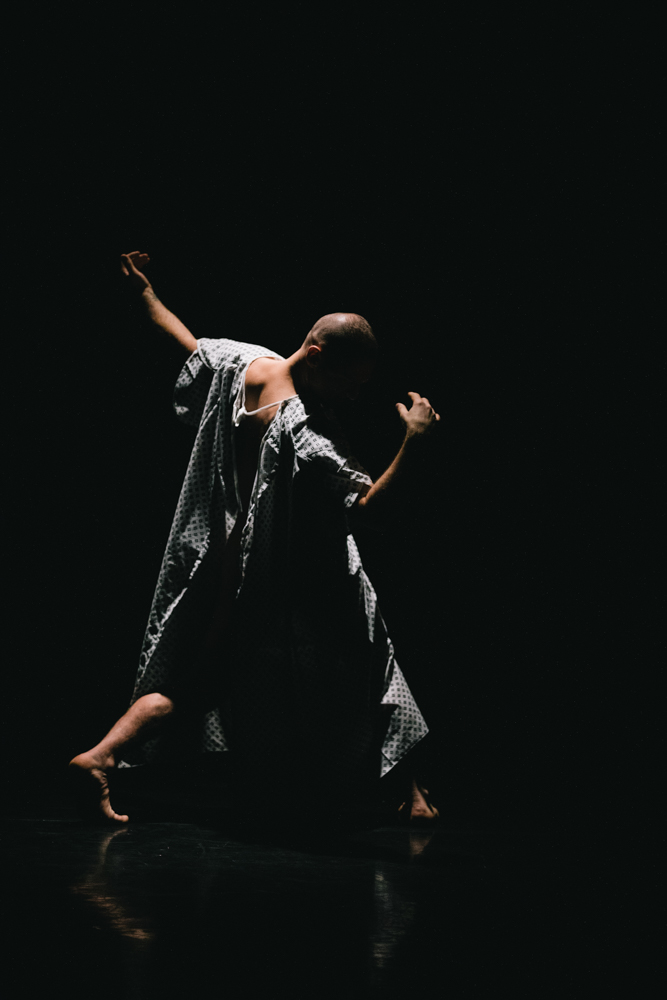

Stuart Waters in A Queer Collision, 2023, Photo by Anthony Edwards

~~

Can you share a little about your dance history and what shaped who you are as an artist?

The dance journey started in school. I was just doing theater and musicals, but when I look back now, I see it was a good way for me to manage my neurodiversity. In the 1980s, I didn’t know that term and didn’t know I was ADHD or dyslexic. I was physical and did lots of sports. Theater offered flourish, and by bringing athleticism and creativity together, I can see now why dance started to catch my attention. I did lots of youth dance.

Then I did the usual steps. I made my way to the Northern School of Contemporary Dance. In the 1990s, they were taking boys for their potential. I’d only done creative dance until that point, no ballet or classical based technique. I was starting from scratch. The training was ballet, Graham, and choreography.

Like most dancers, I trained, and then spent a long time trying to get work. There was a big period where I did lots of project-based work. My introduction to teaching and community-based work became my survival tools and introduced me to different parts of the community through dance. Whatever anybody would ask of me, I would say I could do it. I learned how to teach. What really shaped me was learning how to offer different classes to people with different needs.

Then I was offered company contracts and got into a stream of companies. That bridged my performance and theatrical skills together with my technique. That was the turning point. I started to become a fulltime artist.

There were three main companies I worked with: Motionhouse, where the relationship with my pelvis kicked in; I did a lot of contact improvisation from a more athletic perspective. Then Protein Dance, where my use of voice and character skills came in. And then Wired Aerial Theatre, where I made choreography in a harness in the air. All those companies had a huge connection to teaching.

All through that I also worked with the Center for Advanced Training, which we call CAT schemes, where dancers ages 11-17 train on the weekends with professional artists to give them a path to conservatories. I did a lot of teaching and training around those, which brought me back to the educational and community settings.

I didn’t have a diagnosis of my dyslexia until I started my masters at London Contemporary Dance School. I didn’t realize how much that must have shaped me. When I look back now, I was also very often in generic heteronormative roles. That also impacted my journey. At a certain point, my mental health started to diminish and plummet. Although dance wasn’t to blame, I didn’t realize that the industry and settings I was in were not helping. There was an assumption that we were just going to do emotional work. There wasn’t any real education around how dancers bring emotion to the work.

Additionally, the lifestyle of touring endlessly created burnout. I was working for two companies in the UK and working on my masters and working for a company in Norway and it was just nonstop. I thought it was what I wanted. I was flying around the world but literally at the end of five years I had a breakdown, which was fueled by unmet needs regarding ADHD, anxiety, depression, and addiction.

Essentially, it was a version of burnout. I was depressed and had what people would call an emotional crash, comedown, or hangover. That wasn’t helping my relationship to drugs and alcohol. Addiction kicked in. I ended up in the hospital in 2015 with a near-death experience. I was lucky to survive, and it was a turning point in my career. I used that experience to make a solo show and get back to where I’d left. Everything I’d worked hard for had disappeared because I wasn’t able to show up.

That’s where the mental health interest started. I stopped being a gig dancer for other companies and created a space that I wanted to be in.

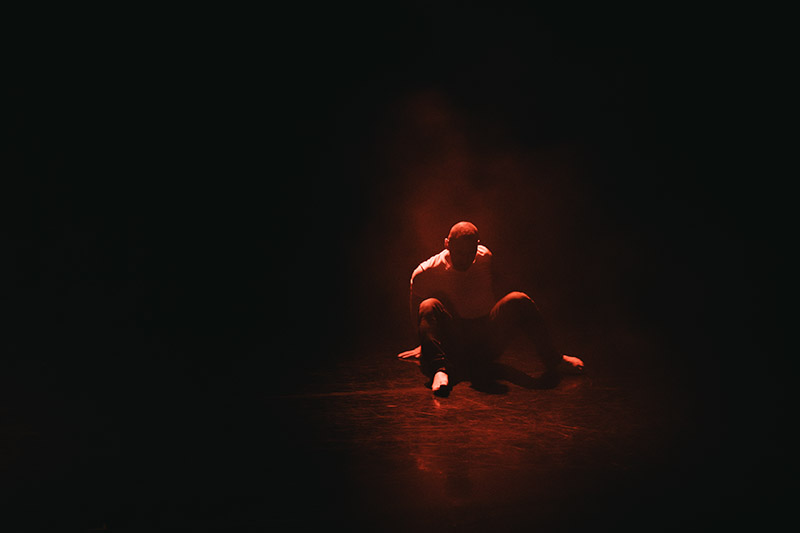

Stuart Waters in ROCKBOTTOM, 2012, Photo by Rosie Powell

How would you generally describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

It’s changing a bit at the moment. Initially, I realized an issue in the dance sector: pathways, opportunities, relationships, and power dynamics make disclosure very difficult for artists. There is a genuine anxiety in artists that they will be replaced, and this hasn’t changed unfortunately. If I explain my work now to people, I say that in the past seven years I’ve come out as disabled. I had no association to disability prior to 2015. I’m not just talking about my ADHD and neurodiversity, which add a complication to my mental health. I’m a dancer with mental health access needs: depression, anxiety, addiction, hidden disabilities, as well as being HIV positive, which shape how I work with people and co-create. I say I’m an artist who makes autobiographical work, but I’m also interested in how we create safe and inclusive spaces for dance, whether that’s a workshop, panel discussion, symposium, or performance setting. I ask: How do you hold audiences when they’re watching emotional work?

The mental health aspect of my work is always in the background, and that is the ongoing challenge. With a live practice, access changes all the time. It never seems to go smoothly and it’s a hard thing to do. In the UK, the word “access” has historically been used more for people with physical disabilities, but now I’m thinking about mental health access and how that exists in my work. And then there’s a whole series of wraparound questions regarding how I do this work without relapsing into anxiety and depression, which impacts my addiction cycle. Anxiety is the big one to manage, and ADHD doesn’t help. This is a common experience for dance artists and one area in my opinion that needs more support, research, and evidence-based practices.

Are there one or two pieces that you’d like to share more about that are particularly emblematic of your work?

ROCKBOTTOM was at the time almost a reaction or impulse; I wanted to make a solo show about my experience as a gay man with mental health problems and addiction. The story focused on the last moments of downward spiral near death. My experience has been what is called a chemsex addiction. I was driven by a passion to talk to audiences about chemsex and the gay community, a subculture within the gay community and in my onion an epidemic that kills men and destroys lives around the world. I used the work to have post-show conversations about mental health with audiences when we toured around the UK. Then COVID happened.

Stuart Waters in ROCKBOTTOM, 2012, Photo by Rosie Powell

A Queer Collision is a progression from ROCKBOTTOM. My producer for ROCKBOTTOM comes from a disability arts background. She saw more disability in me than I saw in myself. We decided we’d have audio descriptions and captioning for ROCKBOTTOM, and I was shocked that 22 years into my career, this was the first time I’d been asked to think about captioning and audio description. We talked about how to engage people who are queer and Deaf or visually impaired and bring them into the work. People usually add access at the end of the creative process. They don’t think about embedding audio description as part of the process to use as a script. My audio describer, Willie Elliot, was a 65-year-old gay man. I approached Willie about finding a way to talk about queer stories through audio description. He agreed and A Queer Collision was born. We recently premiered the show at the Brighton Festival. It was received well by audiences, particularly queer, trans, and disabled audiences and community.

We started with wanting to tell queer stories of marginalization in such a way that visually impaired and blind people could enjoy the show without any access aids, that the access was built in. We had visually impaired and blind friends who critically dropped into the process as we developed different modes of audio description. We got a bit better as we went along writing the script. We practiced describing what we’d done physically. It took a long time.

I worked with this disabled leadership training course, and that helped shape what we were doing. It made me think about what an inclusive space looks like. I wondered how I could go onstage with Willie, us being two white cis men. So I started to think about how we could push the inclusivity of the work. How can we make a traditional venue look and feel different for disabled and queer communities?

In the end, we had the main show with me and Willie, but we also evolved the space through community-based art exhibitions. This included photographers exhibiting disabled, Deaf, and visually impaired communities and platforming their work in the foyers around the building. We had two gender nonconforming contemporary artists create art installation interventions. We had the recovery community, the gender nonconforming and trans community, and the disability community. I asked, “What would it be like to hand my space over to others before I begin?”

A Queer Collision, 2023, Photo by Anthony Edwards

I understand that you’re trained in Human Givens (a model of psychotherapy) which you use as a framework and reference for your own artistic practices. Can you say more about how Human Givens influences your work?

Human Givens came naturally to me when I was working on ROCKBOTTOM. I thought about training as a counsellor as a side gig. I was looking at therapeutic tools and asking how they exist in the studio. Human Givens was good as an introduction to that journey. The idea of human needs was useful for thinking about what I need beyond warming up. I need privacy, connection, rest, community, and communication. This framework of emotional needs is based on research around “emotional triggering” and the amygdala. It was a good start.

The other main takeaway was the idea of emotional arousal. It was helpful to start thinking about the emotional part of my brain. I basically spent my career triggered by being emotionally aroused in dance spaces. It got me thinking about emotional warmups and cool downs. I’ve always liked somatic and embodied practices like meditation, mindfulness, and yoga as active tools as opposed to getting into my hamstrings, for example. I started to think about how somatics and breathwork can support performance emotionally. It definitely plays a big part in my work because it plays into my access needs. A lot of my budget goes into catching and repairing me after a show. The idea of holding performers emotionally requires a budget. I schedule a program that will meet my emotional needs post-performance. I learned I’ve got to make space for those needs.

I always include a check in and a check out with my collaborators. We close and reflect on the day in a check out. Sometimes it tends to be more practical, but if something weird has happened, it gives people an opportunity to share their emotional needs and how they feel. None of that existed in my experience in studios before my breakdown.

That has led me to coaching. I have trained in beginning coaching courses. I haven’t done it on the level I would like to yet, but it’s helped me communicate with collaborators and artists about holding space. My interest started with Human Givens but opened a Pandora’s box around creating an access practice that I do with producers and project managers before I get into the studio.

A Queer Collision, 2023, Photo by Anthony Edwards

I understand an important part of your work is creating platforms like Head:ON through which you discuss mental health safety within creation and performance and share methodologies for safe, accessible practices in studio settings. Can you share more about this side of your work?

Head:ON is currently paused because of lack of funding. It was first launched at The Place when ROCKBOTTOM premiered in 2019. It was a small in-person symposium and a great way of bringing the industry together to talk about mental health access support in dance. In the UK, there’s been a development of people wanting to work as independent artists rather than in companies, so you see more work about identity and mental/physical health onstage. It was about creating a space for conversation. We asked how people can do autobiographical work safely. I felt like historically there haven’t been spaces for artists, producers, and directors to come together and talk about the challenges of holding mental health. There’s an interesting debate about responsibility: Whose responsibility is it? We launched Head:ON conversations during that time, and it felt successful.

Then COVID happened, and Head:ON evolved into free digital wellbeing cafes during lockdown. We’d have online events where people would talk about their work and process to help artists stay connected. We had different guests who were intersectional: queer, visually impaired, even a café on mothers in dance. The last one was about addiction in dance. I talked about my addiction, and we brought in a company that works with addicts. We started with talking about how addiction lives in dance practice, and that opened into conversations around the idea that dance is quite addictive.

All the symposiums have been supported by British sign language interpretation, captioning, and therapeutic care by mental health professionals, so there’s care during the symposiums and then post-care as well. This is something we’re trying to offer in theater settings: mental health therapists so if people are triggered and need to talk, they can.

The next stage is how we can move on from the conversations. At the time, it was about bringing conversations to the surface. Now we’re seeing lots of radical conversations happening, so we need more conversation about what we can do as a sector.

Any other thoughts?

I’ve realized I want to make work about, for, and with vulnerable communities. That clarity has made the space feel more inclusive. There’s always two parts to the work: how do we make the art, and how do we make the space inclusive and safe?

Stuart Waters in ROCKBOTTOM, 2012, Photo by Rosie Powell

~~

To learn more about Stuart, visit stuartwaters.info.