Sistering and Dancing in Community

An Interview with MK Abadoo of MKArts

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

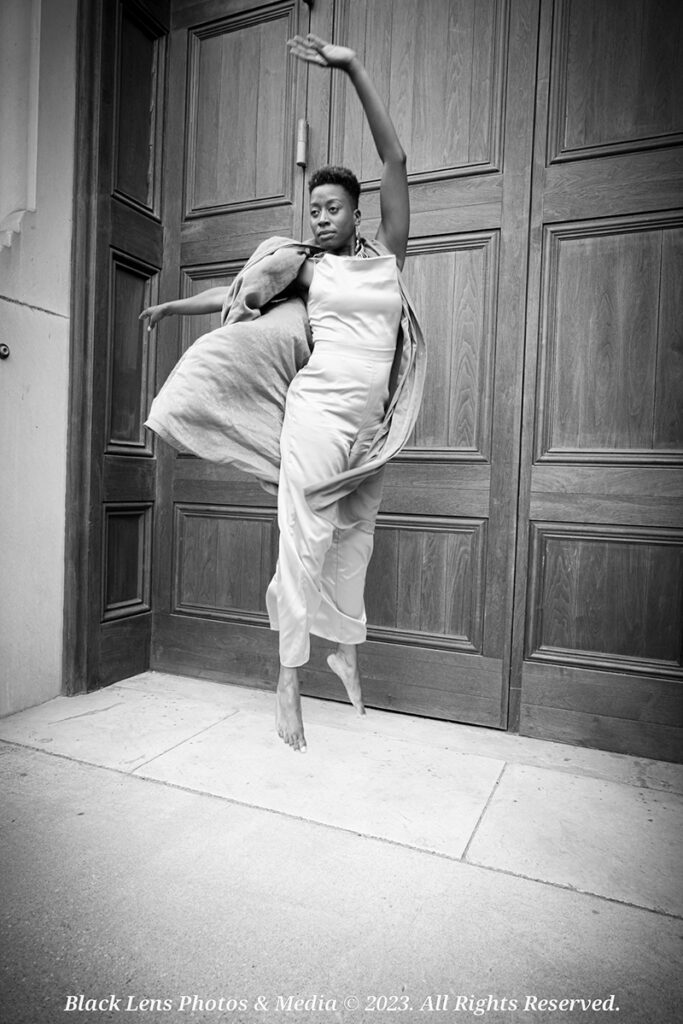

Photos courtesy MK Abadoo

MK Abadoo is the choreographer and director of MKArts in Richmond, VA, an organization that exists at the crux of dance theater and anti-racist cultural organizing. Here, MK discusses how their work seeks to be in accountable relationship with the communities they interact and live in through anti-racist, gender expansive, and inclusive practices such as Sistering. MK also shares how they use an expansive definition of cultural organizing.

~~

Can you share with me a little about your dance history and what shaped who you are as an artist?

My family has celebrated a tradition of cookin’ up dances since I was a little girl. Some of the first dances I learned were social dances my mom taught me in our kitchen. My father was a military parent, so we moved every two to three years. As a way of connecting me to the community, my mom would put me in dance classes. I studied jazz and tap for many years and loved it. I thought I would become a hoofer and had a deep relationship with rhythm, polyrhythm, and the articulation and swag of jazz.

Although I studied these forms from a young age, I was told that I didn’t have any technique when I applied to a high school dance program. I would later learn that by technique, folks meant ballet. In response I immersed myself in Vaganova, a classical Russian ballet style, for many years and it gave me enough “technique” to get into college. I went to University of the Arts because they had a jazz major at the time.

In high school I had been exposed to modern dance, but thoroughly disliked it. In college, I learned about the history of modern dance and was particularly taken by the work of choreographers/educators/scholars like Katherine Dunham, Pearl Primus, and Martha Graham and their relationships to social justice, community, belonging, and identity. That was missing for me in my studies. I was training deeply, but I had to ask myself, “What for?” I learned that dance could serve something larger, and making dances could be about the world and my people beyond just having excellent technique. I ended up shifting my focus to modern and dance education.

I also had wonderful teachers like Kim Bears-Bailey. She’s been a teacher at University of the Arts for decades, and her Horton and Dunham classes became a foundation for my practice. Working with Curt Hayworth was also influential. At first, I resisted the release and somatic based forms that he introduced, but eventually came to love them.

As an undergraduate I also studied dance in Ghana for a year. Neo-traditional Ghanaian dance emerged as a concert dance form within the formation of Ghana’s national identity immediately following its independence. There are traditional dances that people do in their communities, but when they are lifted out of those contexts and onto the stage, they become something different, which practitioners call neotraditional. After graduate school, I went back to Ghana as a Fulbright scholar to continue my research of Ghanaian neo-traditional and contemporary techniques. I specifically studied Agbekor, a widely-practiced ceremonial dance of Ewe heritage, that has influenced my use of rhythm and syncopation.

As a professional touring artist, I worked with Gesel Mason, Liz Lerman, Urban Bush Women, and David Dorfman. My works draw from Africanist use of rhythm, isolation, theme, concept, and narrative, but they’re also informed by a sense of release and non-traditional/ritual use of space. I never envisioned myself as a choreographer until I went to graduate school and found I had developed a strong choreographic practice from working with people like Gesel, Liz, David, and Jawole, who are all amazing choreographers in themselves, but also hire dancers who can workshop material. As a younger dance artist, it was challenging to interpret creative assignments, but I came to love it. It gave me a muscle for making work while not having a lot of preciousness around it. I developed a trust, steadiness and persistence of craft and creative practice.

How would you generally describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

For someone who’s going to come see my work, you’ll almost always bear witness in or to a large circle of multi-generational and expansive movers, all of whom have striking stage presence. It’s going to look and feel theatrical, with elements of modern concert dance, West African forms, funk, jazz, and body percussion. You’ll be immersed within and held closely by the wisdom and experiences of queer, Black cultures.

Are there one or two pieces you’ve choreographed that you’d like to share more about?

Untold RVA presents Brother General Gabriel was a commission by the University of Richmond Tucker Boatwright Festival. It was part of the activities around the commemoration of the first 20 and odd enslaved African folks who were brought to Jamestown in 1619. In 2019, the commission brought together myself and a local commemorative justice community organizer and catalyst, Free Bangura. She coined the term “commemorative justice.” The work she does disrupts traditional preservation tactics around Black narratives as a way to uplift deliberately submerged narratives and also ensure they are amplified in a way that contributes to the wellbeing of Black folks today.

Free is based in Richmond, Virginia, where I moved in 2017. She leads tours within the city, providing untold Black narratives, specifically those that speak to the self-determination of our people. At some of these traditional place markers, she will have a sign with a phone number you can call to receive the undertold story. It’s incredibly powerful work.

We partnered together to not only commemorate the “20 and odd” people and their descendants, but also a blacksmith who was enslaved in Virginia named Gabriel; he organized the largest rebellion for Black freedom in the history of the country. Most people don’t know about it because it was sabotaged and so didn’t happen. But the organization of it would inspire Nat Turner, John Brown, and others.

When I partner with folks, the work I do seeks to support and ensure it’s in service to that community and their self-determined organizing, whether that’s local political power or economic power. Working with Free became a wonderful opportunity to uplift what was already happening locally around the Gabriel narrative. We were invited to engage multiple sites around the city and we landed on the African ancestral burial ground. It’s a powerful and meaningful place in the history of the US because it is one of the oldest. Folks who do this kind of research have said that anywhere from a quarter to a third of African enslaved descendants have an ancestor in this burial ground. It was also the site of gallows where people’s lives would be ended, particularly Black people. But unfortunately in Richmond you could drive past it and never know it was there. Untold RVA presents Brother General Gabriel was an opportunity to draw people, resources, and care to the site. We worked for about a year envisioning and dreaming the event. More than 400 people attended the performances. Each attendee had a Bluetooth headset where they listened to the sound score and were taken around a third of the perimeter of the burial grounds before being taken onto the grounds themselves, where we had a flag folding ceremony that honored the service Gabriel did for our country.

I also co-taught a class with Free called “Dance and Commemorative Justice.” Students from three universities registered for the class where they learned what it means to be a values-driven artist making work aligned with community organizing. We also had nine local community matriarchs who were part of holding the ritual container of the performances. Despite the challenges that come with interweaving so many circles of people, it was an immensely transformational piece that I feel honored and proud to have been a part of.

We planned to restage it in 2020, but then the pandemic happened, so I shifted my focus to a work that was emerging within me called Hoptown.

Hoptown is inspired by the life and the power of my mother, as well as Black women, girls, and gender-expansive people who were born and raised in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, which people from there call “Hoptown.” One of those people of note is the writer bell hooks. She and my mom went to the same high school at different times; bell was a senior when my mom was a freshman.

In 2017, I was having a difficult time in my life and going through many transitions. My mother would visit often to provide support. After I put my child to bed, she’d tell me stories about her life that I had not known before. They were really difficult stories but were also beautiful and sweet. Around that time, I was rereading bell hooks’ memoir Bone Black about growing up in Hopkinsville. It was striking how similar many of the stories were. My mom didn’t know bell hooks, who had a different name in high school. When I told her about the similarities and she read the book, she was astounded. She felt so understood by someone who knew intimately what she experienced.

It had me thinking about what it means to bloom in a space that might feel dark. Over time, what came to me was that my mother and bell hooks were doing what I came to understand as Sistering, a term coined by Dr. Alexis Pauline Gumbs that extends Audre Lorde’s notion that “Sister is a Verb.” I view and practice Sistering as a gender nonconforming ethics of care rooted in African American traditions of tenderness. With this understanding, I was motivated to honor what I experienced with my mother and learned from her stories.

In 2017, Hopkinsville was one of few global sites to best witness the total solar eclipse. People descended upon Hopkinsville to be bathed in the darkness. That became a powerful metaphor, both for the visual lighting design of the piece, but also rich in thematic meaning. Hoptown celebrates bridges of joy and tenderness built across generations of Black women and gender expansive folks as they traverse dark places and spaces in their lives. The eldest member of the piece, Judith Bauer, turned 88 the week of the premiere. Then we have Christine King, one of the second-generation founders of Urban Bush Women. Another of our elder performers is Julinda Lewis who is a writer and artist based in Richmond; she studied with Earth Kitt. Other amazing artists include Sehay, Christine Wyatt, Cryah Ward, and sonic mastermind Asha Santee. The piece follows the arc of a total solar eclipse, dropping into moments of darkness that I call fortified tenderness. It’s immersive, with the audience seated in the middle of the performance space.

I understand an important part of your work is anti-racist cultural organizing, and that you chair the Racial Equity, Arts, and Culture Core of Virginia Commonwealth University’s ICubed, the Institute for Inclusion, Inquiry & Innovation. Can you share more about this side of your work?

It started with trying to understand what it means to be an artist in service to countering injustice. It took some time for me to figure it out. I danced with Urban Bush Women (UBW) for a short time, but trained for many years within their Summer Leadership Institute (SLI). I have since become SLI faculty. Core to this annual convening is the partnership that UBW has with an organization called the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond (PISAB), “a national, multiracial, anti-racist collective of organizers and educators, dedicated to building a movement for social transformation by undoing racism and other forms of oppression.” During the first three days of the SLI, PISAB offers their signature and foundational training called Undoing Racism® and Community Organizing. During this time, we shine a bright light on what we’ve internalized about race while living in a race-based society, both as individuals and people functioning among institutions and systems. It also widens our lens on the history of how racism has been legislated as a practice and how that supports its continuance along with a sense of its existing in the ways we share culture.

I’ve since become a trainer with PISAB and see its executive director, Dr. Kim, as a loving mentor. In graduate school, I was trying to sort out what it meant to be an artist doing justice work. PISAB introduced me to the term “organizing,” which I struggled with. My definition of “organizing” had something to do with direct action, needing a clipboard out in the streets. I was making dances that speak to deep and relevant topics, but is it organizing? Dr. Kim explained to me that culture is “a way of life” and encompasses everything about our life. She further explained that “organizing is bringing people together for an intended purpose.” This brought me to the question: if I’m bringing people together for an intended purpose, what is the culture I am organizing?

That landed on me rather deeply because it means whatever I am holding, facilitating, or participating in, there can be a justice-based mindfulness around what it serves. That could be a dinner party or a rehearsal or a class. In the multiple communities I navigate daily, I view my justice-building work as creating a space that is humanizing for us all. This space must allow us to share culture in a way that connects us to our humanity and deliberately disrupts dynamics of power that may make it hard for us to do that. I do this with a sense of love and kindness. It’s a very loving and accountable integrity practice. If I’m going to bring dancers together or be the steward of a theatrical event, I’m going to look at the dynamics of power I’m working within and ask what needs to happen to connect us to our humanity. That means being honest about what disconnects us from our humanity. For me, because I grew up in a race-based society, it has to do with race, as well as gender and ability.

What do you believe are the biggest impediments to achieving racial, gender, and disability equity in the arts?

If we want to do something different, we have to do something different – but here’s the catch, it’s going to feel different. We can come up with a lot of strategies and plans to do things differently. When we implement them, we must prepare ourselves to feel the discomfort that comes with change. I think that’s where institutions get stuck. For instance, my understanding is that what little funds the US government makes available to artistic productions goes overwhelmingly to historically white-led organizations. This is widely known public knowledge, yet it keeps happening. In order to change that, to make the allocation of those funds more equitable, those organizations will have to get less. For these organizations, that will feel different. It’s up to those organizations to listen and learn from their POC peers. They must look at their history and acknowledge that they have received more, and reach a transformational understanding that when organizations that are challenging racism, sexism, and ableism get supported, everyone benefits. This is hard, especially when inequity and societal conditioning supports competition and a sense of scarcity. I think one of the major things for change to happen is for greater understanding and acceptance of what equity is going to require: transformation for everyone. We’ve all internalized the skills and tools to ensure that the current model keeps going. We’re all going to be uncomfortable with the change and have to learn how to be okay with it.

What’s next for you? Do you have a project or focus you’d like to share more about?

Hoptown premiered May 19th in Hopkinsville, Kentucky at the Pennyroyal Arts Council Alhambra Theatre. It was a resounding success! It is a co-commission by National Performance Network between Dance Place in Washington, DC, and the Alhambra Theatre, so it will be performed at Dance Place in the fall of 2024. I’m currently looking for places to perform it in Richmond, Virginia and also hope to join the mid-Atlantic touring roster for the ‘24-’25 season.

I also want to return to the development of my work LOCS and present it at the Chale Wote Street Art Festival in Accra, Ghana next summer. LOCS is an iterative and intergenerational duet that amplifies and extends a site of body contact (25 feet of hair, 50-foot barbering cape, etc.) to unravel the question: what has been woven into us?

~~

To learn more, visit www.mkabadoo.com.