The Movement of Memory

BY MARY TRUNK; ALL IMAGES COURTESY MARY TRUNK

Note: This essay was first published in Stance on Dance’s fall/winter 2022 print issue. To learn more, visit stanceondance.com/print-publication.

In January of 1982, Santa Cruz, CA experienced a gigantic rainstorm that shut down the University (UCSC). The winter quarter was about to begin, and I was desperate to audition for the dance department. My major was painting and while I fantasized about becoming a dancer, I assumed that starting in junior high was too late to even consider it as an option. It wasn’t until I happened upon an impromptu modern dance rehearsal in an empty dining hall that I thought there might be a way to pursue it. Every day I rode any bus that happened to be going in the direction of the campus. Each time I would find the dance studio dark and empty. It was weeks before things were back to some kind of normalcy. I managed to make it to the audition, and I remember two things – doing plies and hearing the dance department chair whisper in my ear, “Where have you been?”

UCSC is sprawled along the hills above Santa Cruz. You can sit in the quiet of a grove of redwood trees while looking down at the crowded boardwalk and hear the screams of the roller coaster riders echo up into the woods. They were two separate worlds: a working-class beach getaway a few miles down the hill from an artsy liberal university that didn’t have grades. Now it’s a bedroom community for the owners of rich Silicon Valley tech companies. No longer can you rent a room for less than $100 dollars or even $1000, and the university has adopted grades. But when I was there, I had no problem living on Top Ramen and hard-boiled eggs. I never felt broke because I had fallen in love with dancing, and I was doing it every day.

The founder of the dance program, Ruth Solomon, called that time the golden age. She had the innovative brilliance to create a program that focused on choreography. She invited world renowned dancers, choreographers, and musicians to work with us: Meredith Monk, Betty Walberg, Robert Ellis Dunn, Gus Solomons Jr., and Gordon Mumma. It was an all-encompassing experience. Crazy ideas like taping garbage to the wall, dancing in trees, on blocks of ice, and hoods of old Cadillacs were encouraged. We learned structure and the rewards of self-discovery. We had time, space, and freedom. All art was available for inspiration and example. I wrote haikus, made costumes out of grass, and memorized Steve Reich’s “Clapping Music.” The world was open to us. We were seen and understood, and we were taken seriously. We became artists.

We were direct descendants of the postmodern dancers of the ‘60s and ‘70s. While we trained in ballet and other techniques, our work was an exploration outside of the constraints of convention. We included props, theater, spoken word, pedestrian movements, non-dancers, and we used alternative spaces to show our work. Experimentation, chance, and playfulness was the priority. We used it all with no hesitation.

Graduating and leaving that fertile, small world on the hill was not easy. The safety net, the camaraderie, and the friendships were not as accessible as they once were. Some friends went to New York, others to San Francisco, including myself, and a few went back to their parents’ homes. But the need to work and to create stayed with me.

So, I worked shitty jobs, lived on meager earnings, asked friends and acquaintances to be in my work without pay, and I made dances. For more than 10 years, I ran a dance company and produced numerous shows at every local theater in San Francisco I could afford.

I saw the possibilities of dance and film when I discovered videos of Pina Bausch and her company. She had not yet performed in the US, and the only way I could see her work was to view video tapes at the Goethe-Institut library in San Francisco. I saw in those images the potential for movement to be transformed, embellished, and fragmented. I started filming dancers with a Super 8 camera. My shows soon included live dancers and projections. My choreography expanded into another discipline altogether. While I sometimes mourned choreographing in the studio, I could also see how film broadened my view of dance. It intensified and refueled the drive and motivation that began in Santa Cruz.

Keeping a company together became increasingly difficult. The balance of work and creativity was exhausting. The idea of cleaning more toilets or getting coffee for my boss every day started to get old. Graduate school seemed like a possibility. Maybe I could teach film and make a living? So, I applied and was accepted at the San Francisco Art Institute. I was introduced to incredible groundbreaking experimental films. I also experienced the poetic originality of Maya Deren and Chris Marker. Film and dance connected through movement, metaphor, poetry, sound, and emotion. I found a possible approach to teaching and I have been teaching since the ‘90s.

Over the years, I have often wondered why my experience at UCSC was so impactful. How could a short period in my life sustain its influence and even grow? Was I alone in feeling this? Was the convergence of creativity as pivotal for my friends as it was for me? How does the language of dance communicate on so many levels and to all kinds of people? I wanted to find out and I wanted to recapture that coming together of creative minds. I missed it and I missed my friends. Film is how I would do it. Recording the present as well as the recollection of the past. For more than 15 years, I ruminated over this project. I needed that time to learn more about film and figure out my direction and perspective. And then I dove in, and Muscle Memory was in motion.

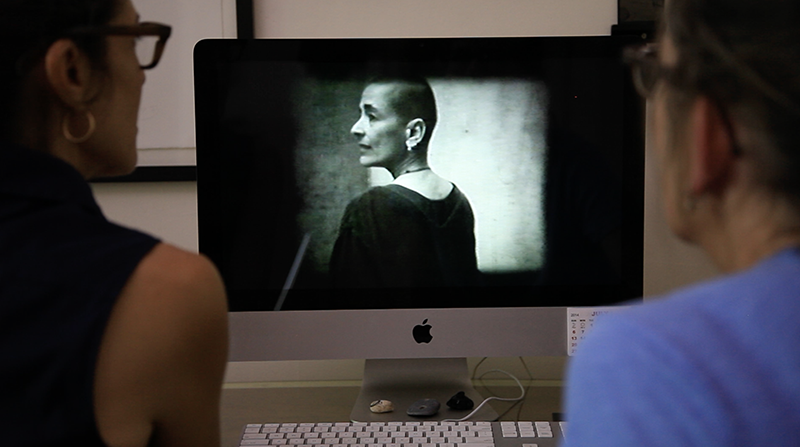

I wanted my friends to tell me what they remembered, and I also wanted them to dance again. All of us are in our 50s and 60s with the keen awareness that we can no longer move as we used to. What can I create that truthfully investigates how meaningful dance was for us then and whether it still is now? I wanted my friends to participate and collaborate. I asked and they said yes. Some of us had not spoken for a decade. And while old alliances, resentments, insecurities, and body issues did rear their heads, being together gave us courage. Age and experience became an asset and an inspiration.

Two things were very clear. I would explore the relationship between choreography and video, and how they can be used to enhance the stories and experiences my friends revealed. And for the first time, I would participate in the film not just as a filmmaker, but also as a dancer and interviewee.

My friends/dancers were given written movement instructions. They interpreted and memorized the sequences. The words describe movement that is gestural in nature and intimate in tone. The dancers did not get direction from me until after they created their own meaning in the movements.

My methods rely on the collaboration, cooperation, and interpretation of the dancers involved. I set up structures, and the material that is developed informs my film direction, camera movement, composition, and setting. The dancers interpret the movements, set the pace, and emphasize moments. I decide where they will perform, who they will perform with, how often they will do the phrases, how fast, and how slow.

I give no other directions regarding tone, emotion, or style. In this way the dancers allow the movements themselves to influence how it makes them feel. Clenching fists and jumping frantically feels very different than writhing on the floor in slow motion. The dancers create the narratives that help them remember the movements. Then they show me what they have created and that in turn generates new ideas and narratives for me. The movement sequences are metaphorical and symbolic, and become important dynamic communication in partnership with the spoken words and interviews.

The camera is part of the choreography and films the dancers from many different angles and shot sizes. The camera person, myself, often becomes part of the dance, moving with and around the dancers as they are being filmed. I observe and allow the movement to direct my choices as a filmmaker. From that material, I pull out sections that resonate most for me and, with the help of my editor, Caren McCaleb, we put together the strongest screen dance moments.

Seeing dancers in middle age is not common or accepted. Dancers are supposed to be young, often tiny, flexible, and full of energy. Not chubby, wrinkly, and creaky. And yet, the dancers in Muscle Memory can access who they used to be. The motions may be smaller but the memories in the muscles are still full of emotion. They still feel the thrill and excitement of moving together, of learning work, of discovering and creating meaning in it. There is an intrinsic dignity to the movement that comes through in their bodies even now.

I decided early on not to conduct formal interviews. I wanted viewers to witness the intimacy of our friendships. I included myself in the frame which results in a conversation more than an interview. In other sections, I filmed extreme close-ups where the dancers look directly into the lens. This offers a more internal perspective of their recollections. If viewers see people in a film looking directly at them while revealing intimate personal thoughts and reflections, there’s a much better chance they will care.

For other sections, I asked the dancers to sit at a card table with a visible microphone. I gave them a stack of index cards with personal questions and asked them to read the cards out loud and answer any, all, or part of them. This is another way to engage viewers with personal revelations while at the same time prompting their imagination to fill in the blanks when questions are not answered.

The dancers share personal stories that have deeply affected their lives and they reflect on themes such as age, family, relationships, identity, regret, and friendship. The dance sections use movement language to emphasize, explore, and share what cannot be verbalized. The ambivalence of getting a face lift, the shame of being homeless, the disappearance of the creative urge, losing a partner to a devastating brain tumor, and undergoing electric shock therapy are all revealed in words and movement.

Most of my friends were quite generous with archival footage and photographs from their past. Years into the project, when I had a refined rough cut, one friend handed over 25 VHS tapes. I was both excited and freaked out. Was this footage even usable? It was a treasure and revealed early versions of what would become brilliant choreography. Performances in attics and basements, youthful bodies smoking, drinking until dawn, and laughing about making it to ballet class by 9 a.m. magically reappeared. Here was the evidence of our devotion, our extreme commitment to dance and play. We had to include it. So, my editor and I proceeded to redo almost the entire film. As difficult as that sounds, the film is much better for it.

Six years in the making, the film is free of sentimentality. It is a recognition of an extraordinary time when we were free to be daring and original. It reveals the heartbreak, joy, and realities of being an artist, the inevitable physical changes, regret, disappointment, and the accomplishments we experienced. Working together again revived the love of dance despite some limits of our bodies and the reliability of our memories. The journey of creating Muscle Memory returned us all to a place of joy, a place that is accessible at any age.

~~

Mary Trunk is a filmmaker, choreographer, and multimedia artist living in Altadena, CA. She has been producing and directing documentaries, dance videos, experimental hybrid films, and paintings for more than 30 years. Mary is also a film, video, and screen dance professor at Loyola Marymount University, Mount St. Mary’s University, and Art Center College of Design. She is a graduate of the University of California at Santa Cruz and the San Francisco Art Institute. Her work can be found at www.maandpafilms.com, www.musclememoryproject.com, and @marytrunk.

Readers can access Muscle Memory for free until February 1st, 2023 by visiting vimeo.com/739270881 and using the password ‘Memory.’ Two earlier films, The Watershed, (promo code: TheWatershed) and Lost in Living, (promo code: Lostinliving) are available to rent for free until February 28th, 2023.

Note: This essay was first published in Stance on Dance’s fall/winter 2022 print issue. To learn more, visit stanceondance.com/print-publication.

2 Responses to “The Movement of Memory”

Thank you for watching and reading, Elizabeth!

This film is interestingly a kind of personal documentary, yet objectively and beautifully tells the story of the UCSC dance department and this extraordinary group of people. Wonderfully engaging and entertaining.

Comments are closed.