Saving Space

An interview with Joe Landini

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Joe Landini is a choreographer and arts administrator in San Francisco, CA and the founder and current director of operations at SAFEhouse for the Performing Arts. SAFEhouse was founded in 2007 and has been housed in four different venues around San Francisco over the years. Each of these four spaces has been an integral part of the freelance contemporary dance community in the Bay Area by being an accessible incubator for works in progress. Here, Joe shares what his ride has been like running SAFEhouse in its various iterations over the years and how it intersects with his own choreography and creative endeavors, like his recent 90 Days of Creativity.

Photo by Robbie Sweeny

~~

Can you tell me a little about your dance history and what shaped who you are as an artist today?

I started off as a jazz dancer when I was 17. I had terrible alignment, so I went into ballet. Then I blew out my knees, since I was waiting tables and doing ballet, which is a bad combination. I did rehab. After rehab, I went to UC Irvine and did my undergraduate degree. That’s where I got turned onto contemporary dance. I worked professionally as a choreographer for a few years and then went back to school and got my masters at Trinity Laban Conservatoire in London. When I finished my masters, I moved to San Francisco and opened SAFEhouse and The Garage at the same time. SAFEhouse was originally the nonprofit, and The Garage was a nickname for the space. The Garage had two locations in San Francisco, and they were underground artmaking, very DIY. When SAFEhouse moved to its third location, it was upstairs above a Burger King and obviously wasn’t a garage, so for branding purposes it made sense to change the name to SAFEhouse for the Performing Arts, which was the name of the nonprofit anyway.

What was the impetus behind starting SAFEhouse for the Performing Arts?

I had done an 11-year internship with a producer in San Francisco called Footloose who ran Shotwell Studios. After 11 years, I had a lot of philosophical differences with them; I had developed my own style as an arts administrator. In 2007, San Francisco was coming out of the .com crash and there was a lot of affordable property. I knew exactly what I wanted, so I just walked up and down the streets looking for a garage with high ceilings and storefront access. I found a handwritten note on a garage south of Market. I called the number on the note, and it was an older Russian woman named Ludmilla, who was about 80, who asked if I wanted to look at it now. I said sure, so she said she would send someone over with the key. This older Latino gentleman biked up, gave me the key, and biked away. I opened the door, and it was literally an old garage with car parts. It had a sunken floor that was perfect to build a sprung floor for dancers, and it had this amazing basement. I called her back and said I’d take it. That was the first location of The Garage.

It was a very classic black box theater. I had collected a lot of theater equipment through the years. There was a space I had managed called the Jon Sims Center. They went bankrupt and I purchased their equipment: old metal risers and a lighting system. We were there for three or four years and made our neighbors insane with noise, so they kicked us out.

The flagship programs at The Garage were RAW and AIRspace. RAW stood for Resident Artist Workshop. It started with my previous employer, Footloose. Originally it was called Raw and Uncut, but I shortened it to RAW and came up with the acronym. AIRspace was given to me by the Jon Sims Center when they went out of business, and it had funding attached to it. It was specifically for LGBTQ artists. Those two sister programs sat side by side, though RAW was much larger.

I had all these friends from Footloose and Jon Sims, and we were all struggling with the same set of circumstances, which was no one had rehearsal space. It made sense to me that a time share model would work, and that model ended up being successful. My twist was it was more of a collective; we took turns cleaning the bathroom and typing up programs.

We got 501c3 status pretty early on. There’s permanent funding in San Francisco called Grants for the Arts, and I wanted to get on their roster. Once a 501c3 got on their roster, they were guaranteed funding every year, which makes a really big difference. They are very supportive of venues because the funding comes from the Hotel Tax Fund. People visit San Francisco and pay taxes on hotel rooms to see shows. It’s not officially permanent funding anymore, but it’s still consistent. You have to reapply every year and maintain a certain level of work to be eligible.

Photo by Robbie Sweeny

What are some of the different iterations of SAFEhouse over the years?

After we got kicked out of our first location, we shopped around, as property was still affordable. This was in 2010. We found another good deal on another garage a few streets away. By that point we had a lot of momentum. Funders knew who we were. We recreated what we had at the first Garage. It was the same size but without the basement.

Funders wanted us to be closer to downtown and pledged to increase our funding if we moved. The second Garage was eight blocks from Market Street, and funders wanted us to be closer to public transportation. It was also a dodgy walk. A company called KUNST-STOFF had just left a functional space on the second floor above a Burger King with a gorgeous view right on Market Street. We moved in 2015. We were in the middle of Central Market, and we really flourished. At that point, the tech community had taken hold in the Bay Area and leases were skyrocketing. Burger King, who was our landlord, wanted to increase our rent by 40 percent. At that point, we left because our lease would have been 60 percent of our budget with none left over to pay artists. Our first Garage space was $2,000 a month; the second Garage was $3,000 a month; at the third location above Burger King, we paid $6,000.

By that point, I had developed a good relationship with the mayor’s office. I found a storefront in the Tenderloin in 1995 and waited 20 years for it to become available. It was an old porn theater and gay strip joint. I always thought it would be a great dance space. They said the strip joint was closing and if I was willing to take on the lease, they could give me the funding to renovate it. It ended up being $200,000 to renovate it. We still had our space above the Burger King, so the city literally paid our rent on the new location while it was being renovated. We opened in 2017. We got a 15-year lease and discounted rent. It’s small and intimate, exactly the same size as the first Garage. It’s also close to several other theaters and arts groups.

What has been your experience directing SAFEhouse all these years, especially as the city has changed?

It’s been good and bad, mostly good. We’ve specialized in works in progress for 15 years, and I ran everything by myself for 10 years. After 10 years, it was hard seeing so much unfinished work. Now I can appreciate what an amazing honor it is to see work before it’s finished.

SAFEhouse has been experimenting with distributed leadership and challenges around equity, which has been a big deal as a white led organization. We’ve had some successes and a lot of failures. The distributed leadership has been an interesting experiment. We made a conscious choice to go to BIPOC communities to look for staff. We worked with an equity coach for a year and that was eye opening. It sometimes feels like an uphill battle to dismantle some of white supremacist practices in the arts. We tried to be a cooperative but all we managed to do was attract more white artists. We switched to distributed leadership because it felt like we could be more intentional. That has been successful to a degree. The big challenge now is finding enough funding to pay a large staff.

Coming out of COVID is really hard. Audiences haven’t come back to contemporary dance. The larger venues have done better, but we have fewer resources for marketing. It’s going to be interesting to see what the next few years look like. We’re still asking people to be vaxed and masked whereas some of the larger venues are not. There are some audiences who don’t want to wear masks, and other audiences who don’t feel safe with just vaccinations. We try to find some middle road that’s comfortable for the largest segment of people, but with all those challenges it’s been hard to get audiences to come back.

Photo by Robbie Sweeny

How does your choreography intertwine with all this?

Distributed leadership has allowed me time to focus on my own work because I no longer have to take on all the responsibilities as an executive director. I just celebrated 30 years of choreographing. I’ve made a lot of site specific and score-based work rooted in audience participation and challenging the role of the viewer. I’ve made site specific work at ODC, Fort Mason, and the Joe Goode Annex. When I was at Laban, I studied European dance theater and that has informed my work. I play with the idea of immersive work where the audience is drawn organically in as co-conspirator. It’s not just audience participation; the audience is driving the work. I find that really rewarding.

What is 90 Days of Creativity and how is it organized?

Once SAFEhouse started the distributed leadership model, I had the space to explore my next phase of creativity. I wanted to do something new, so I explored creative coaching. It felt like an area of strength because I had mentored so many artists. I had this idea of finding a group of artists to work together for 90 days. The group works together on Zoom every Monday. It’s a very gentle accountability session to set goals and check in with people. Each week we have a theme. Some of the themes we’ve tackled are creative methods, fears, the role of audience, etc. Each day I post something on my website or on Instagram about creativity or something creative happening in the Bay Area.

Soon we start four weeks of live workshops. The participants will come to SAFEhouse and lead some aspect of the workshop, and then I’ll help them create a performance score. We have musicians, writers, actors, and choreographers. For four weeks, they’ll bring what they’ve been working on into the room, and we’ll workshop it. On the 90th day, there will be some sort of gathering and sharing.

What has been your experience of 90 Days of Creativity thus far?

It’s been pretty organic. I needed a break from making work; my 30th anniversary show was challenging coming out of COVID. It’s been a nice change to focus on other people rather than myself. In a month, we’ll start the process again with another 90 Days of Creativity. The next round will have two levels – a free level and a paid level. The other thing we’re going to add is professional development. That’s always been something our community has struggled with. It’ll be hybrid; the Zoom sessions will continue alongside the live workshop component. People from other parts of the country have been participating in the Zoom component, which has been interesting.

What’s next for you? Is there another project of focus you’d like to share more about?

I’ve been invited to participate in a couple of pop-up spaces. Because I’ve run four spaces, people say, “We have space, someone call Joe.” I’m also trying to figure out what’s next for me choreographically. I want to do more traveling and teaching, get out into the world a little bit more.

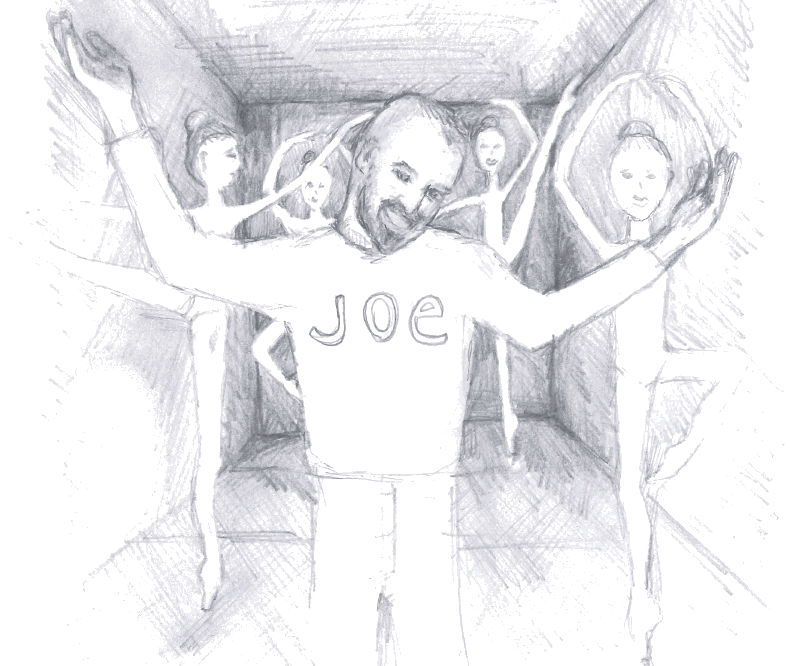

Illustration by Maggie Stack

~~

To learn more, visit safehousearts.org and joelandinidance.com.