Jung Soo “Krops” Lee: “Disability Isn’t Only What You See”

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Jung Soo “Krops” Lee is a b-boy and DJ in Uijeongbu, South Korea. He joined the breakdance crew Fusion MC in high school, becoming its youngest member. During his first year with the crew in 2012, he won his first world competition, Chelles Battle Pro, in France. The following year, he won Battle of the Year in Germany. In November 2013, he landed on his neck during a practice and became paralyzed. After strenuous rehabilitation, he has continued to dance as well as DJ for Fusion MC. He also performs with ILL-Abilities, an international crew comprised of dancers with disabilities.

Listen to the audobook recording of Jung Soo “Krops” Lee’s interview here!

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book, visit here!

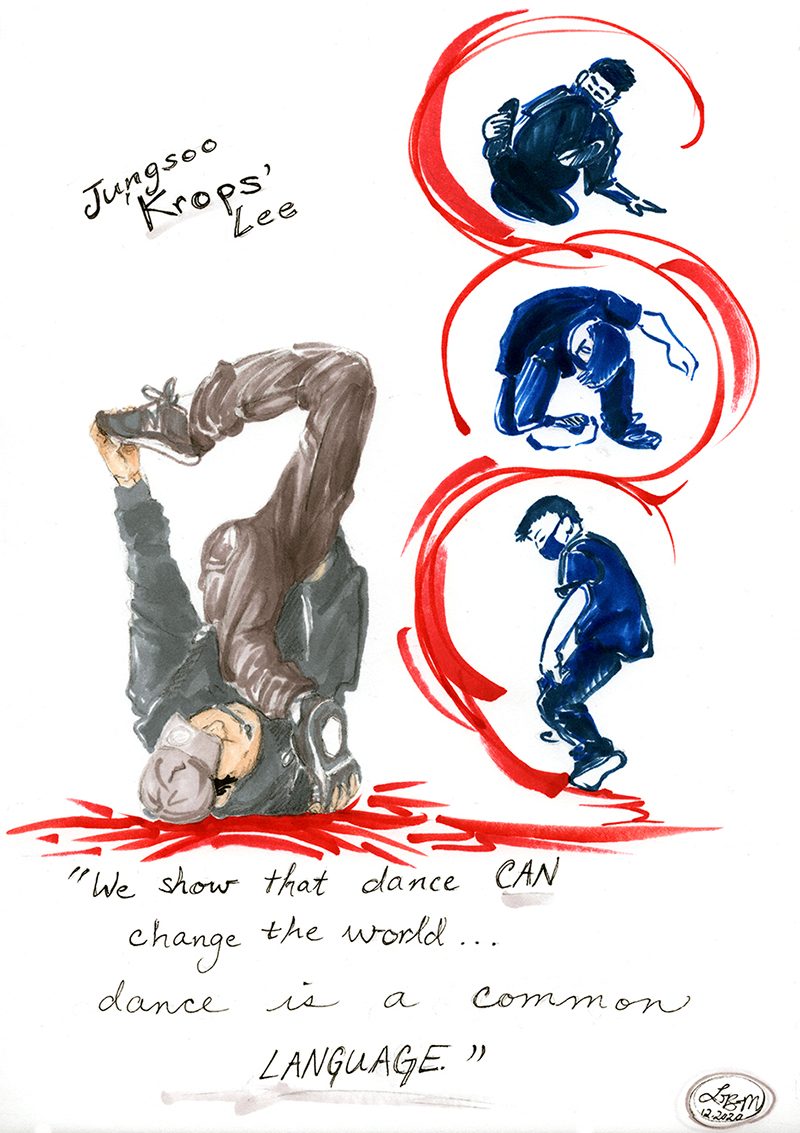

Image description: Krops is depicted laying on his shoulders with one foot in the air and the other on the ground in front of his shoulder. His right hand reaches up to touch his foot. He is wearing gray. On the side encircled in red ribbons of energy are three smaller blue depictions of Krops in various breakdance moves. The main image rests on red energetic lines with the quote, “We show that dance can change the world…dance is a common language.”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

I started to breakdance when I was 11. I saw a video online of one of the biggest b-boy competitions called Battle of the Year and said, “Whoa that’s crazy.” I tried to learn the moves from the video. I kept practicing and when I was 16, I joined a crew called Fusion MC, which is one of the biggest b-boy crews in Korea. When I was 17, I won the world competition called Chelles Battle Pro in France. The next year, I participated in Battle of the Year, the competition where I first saw breakdance, and won. I was one of the youngest highlighted b-boys in Korea.

Later that year, I was practicing a windmill for a competition. I was supposed to do a flip and land on my back and go into a spin. I fell and landed on my neck, and my spine was damaged. My body was totally paralyzed. I went to the hospital and was in a coma for a few days. In Korean hospitals, there is a room where patients go before death. When I woke from my coma, I was in that room. My doctor thought I wouldn’t wake up and would die soon. He thought I needed several surgeries to stay alive.

A miracle happened. I didn’t even need surgery. My doctor said rehabilitation would take five years in the hospital, but it took only one year. Basically, I’m handicapped, as I will never be cured 100 percent. For example, I still don’t feel temperature when I touch hot things. But in Korea, there’s a law that you need to have surgery in order to be considered handicapped and get money from the government. So I’m considered a normal person in Korea even though I have a handicap. I don’t get any support from the government. After one year in the hospital, I went home and continued my rehabilitation on my own.

My crew Fusion MC had a donation to help pay my hospital fee. Many fans and fellow dancers donated. I’m not rich, so I felt that all I could do to give back to them was get back to the stage.

After my rehab, I went to the gym and danced some simple steps. One time, I played the music for the crew, and I felt like they were dancing for me, so I decided to be a DJ. I loved contributing to the crew and it also helped my rehabilitation. When you have a spine injury, the most important thing to do is give sensors to the lost parts of your body, especially fingers and toes. DJing was helpful for me, especially playing the keyboard. It became a new goal.

I can only dance 20 percent of what I could before. I liked to do a lot of head spins and windmills before my injury, but I can’t do those anymore, so I’ve changed my style. In breakdance, there’s a step called threading where you make a hole with your body and thread your limbs in or out of it. I focus more on that now. It’s more detailed and not as active.

My spine injury is an invisible handicap. For example, when I’m dancing, I feel like something is stopping me. If I send a message to my right hand to raise it up, sometimes it works, other times it’s like something blocks it. My handicap is affected by weather and temperature as well.

In 2017, one of my friends in Europe invited me to judge a competition. That’s where I met Redo, a member of ILL-Abilities. I already knew about ILL-Abilities, and I really wanted to join the crew. I felt like the only way for me to give back to all the donations I’d received while I was in the hospital was to go back to the stage, and ILL-Abilities was all about achieving the impossible. I did a workshop with Redo. After that I met Kujo, another member, and they both agreed I could join.

Each show and tour have been unique and epic. After the shows, the audience cries and gets emotional, but every country has a different vibe. For example, when we went to Japan, we taught a workshop where everyone was really strict and focused, but after our show they were laughing and crying. In Mexico at our last show, people got up and started dancing with us.

We show that dance can change the world. Whether you are handicapped or not, dance is a common language.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

I dance for six or seven hours a day with my home crew, Fusion MC. That includes stretching, free form, and practicing routines for shows. I don’t battle anymore, but I teach workshops and perform.

ILL-Abilities and Fusion MC are my family. That’s the most important thing. Because of them, I dance the best I can, always.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

“Why are you fat?” In Korea, people think b-boys should be in really good shape. My injury is invisible, so people don’t know about it.

It’s weird because I am a young person, but I’m considered a part of the older b-boy generation. I won world competitions when I was 16 or 17, which is unique. The older b-boys still see me as a fellow b-boy, but the younger generation only knows me as a DJ.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

When I got injured, many people sent me donations. When I woke up and finally left the hospital, they said, “Yeah Krops is back! He made it!” But because my disability is invisible, some of the people who sent donations said I was acting just to get money. It made me depressed and I needed medicine every day. A good friend finally asked me, “Why are you giving time to people who don’t love you? Don’t try to change the people who dislike you. Just give back to the people who love you.” After that, I changed my mindset and did my best.

Another thing that bothers me is that some people think I’m the DJ for ILL-Abilities. They don’t realize I have a disability and I’m one of the crew. They see me as a normal person, thinking that handicapped people need wheelchairs and crutches, but disability isn’t only what you see. That changed when we started to introduce ourselves as part of the showcase. When I tell my story, everyone 100 percent changes their mind.

There are a lot of people who have an invisible handicap, not only in the body but also in the mind. That’s become my own mission: to educate people about invisible handicaps.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

There aren’t dance opportunities for people with disabilities in Korea. Besides me, there’s only one other b-boy with a disability in Korea; he is missing a leg. I’ve been trying to do free workshops for people who have disabilities. I have a contract with an education company. In Korea, people wonder why handicapped people need to breakdance. Since it’s very active, they think we will get more injured. Koreans are more open to people with disabilities learning to paint or sing, but not dance.

There is one place in Seoul for young people with disabilities to learn dance, but it’s not big. It’s a company that works for the government. In other cities they might be able to go to a private dance studio and learn, but there’s no specific place where handicapped people can go and dance. I know some Korean people are trying to do events for people with disabilities, but it’s still less than other countries.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

Yeah, for sure. Dancing is a common language; everyone can dance. I am crossing my fingers that there will be more options for handicapped people to dance in the future.

I think dancers in general don’t care if someone has a disability. In Korea, artists are more open than the general public. When I go to competitions or events, everyone thinks ILL-Abilities is one of the best crews, not because we have disabilities, just because of how we dance.

What is your preferred term for the field?

Korean uses Chinese symbols to describe words. In English, there is a difference between “handicapped” and “disabilities,” but in Korean, they’re the same symbol.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

I think it all depends on what I do. If I make a good path, maybe things will change. We don’t have much history with disability in Korea. I hope handicapped people will see me, and then maybe they will change their mind and start to dance. I really want to show people that anything is possible, but Korea isn’t open yet.

Since I wasn’t born with a disability, I wasn’t interested in handicapped people until I got injured. I thought everyone could access dance and had good opportunities. Now I know that handicapped people don’t have many systems to support them. My goal is to make more opportunities.

Any other thoughts?

While sometimes I get depressed about my dancing because I can’t do what I did before, I’m trying to do my best professionally. I’m trying to show people that anything is possible, but it’s still hard for handicapped people in Korea. I’m crossing my fingers that we will overcome this situation.

Pictured: Krops, Photo by BAKI

Image description: Krops is balanced on his head and one arm with his legs and other arms bent above him. He is wearing black pants and shirt, tennis shoes, and a cap. The photo is in black and white.

~~

To learn more about ILL-Abilities, visit www.illabilities.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

This interview was originally conducted in July 2020.