Hai Cohen: “I Would Like to See Good Dance, Period”

BY SILVA LAUKKANEN; TRANSLATED BY HAI COHEN; EDITED BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Hai Cohen was born in Jerusalem and became paralyzed from the chest down after jumping into the shallow water of a swimming pool. He became a music editor in the army radio station and studied Philosophy. Hai graduated from the Sam Spiegel Film and Television School and went on to create documentary films. He is a dancer, teacher, and co-manager with Tali Wertheim at Vertigo Power of Balance, which operates out of Vertigo Eco Art Village near Jerusalem. He has practiced contact improvisation since 2000 and leads workshops and projects in disabled and non-disabled contact improvisation in Israel and abroad.

Listen to the audobook recording of Hai Cohen’s interview here!

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

לקריאה בעברית נא לגלול למטה. (To read in Hebrew, please scroll down.)

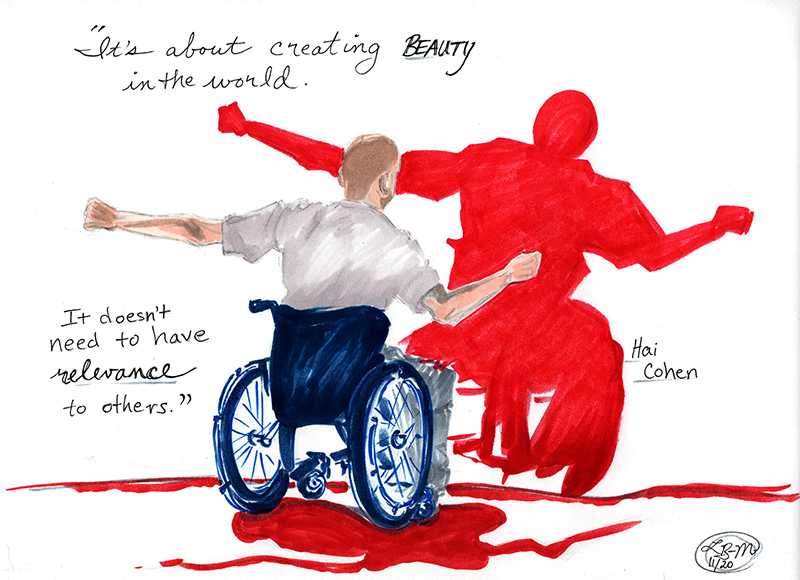

Image description: Hai is depicted facing back with his arms extended to the sides. His wheelchair is blue, he is dressed in gray, and he casts a large red shadow of his image as if he is facing a wall. The quotes, “It’s about creating beauty in the world” and “It doesn’t need to have relevance to others” hover around him.

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

I was injured when I was 13. I jumped into shallow water in a swimming pool. I got back to so-called “normal life” in high school. In Israel we have the army so, after high school, I volunteered for the army and became a music editor at the army radio station. After that, I studied film for five years and ended up making documentaries as well as experimenting with video. While doing some research for a film in 2000, I met a dancer who invited me to an integrated dance workshop. I said no, that it was not my interest, but she insisted so eventually I joined. The workshop was through Vertigo Dance Company and hosted by Adam Benjamin for the creation of a new piece. The workshop was three days long and was very powerful for me.

After the workshop, Adam went back to England and then came back to Israel to start working on the piece. It was two or three months of rehearsal and, a year after the workshop in 2001, we premiered the piece. There were four participants with disabilities who joined the original cast. The name of the piece was Power of Balance. We performed it for three years.

At the same time, I was researching contact improvisation with Tali Wertheim. We wanted to figure out how to continue integrated dance in Israel. One year into performing Power of Balance, I began teaching. It was the start of a branch of Vertigo Dance Company, also called Power of Balance, that is an integrated dance center for people with and without disabilities.

Tali and I taught workshops and created some works for the stage, including a duet and a trio with another dancer, Maya Resheff, who is not disabled. The trio, 11,711 Stone Steps at Nikko, was a highlight for me because it incorporated haiku. I try to incorporate haiku into everything I touch. When I worked in film, I tried to create cinematic haikus, and with this piece I was trying to make a dance haiku within the structure and spirit by using contact improvisation.

I’ve also been part of the Israeli contact improv association that has been around for many years. I think the first festival was around the time I started dancing, and it grew slowly over eight or nine years. It is very significant for our work, which is not only directed to the integrated dance field but also to the contact improvisation field in Israel and around the world.

As far as other highlights, in 2007, Alex Shmurak (a dancer and a friend) and I did a collaboration with a company in Ethiopia where we choreographed Adugna. I also made a documentary about the project. In 2013, we did a co-production with Gerda König called HOMEZONE. Now, we’re in the middle of a new process by choreographer Sharon Fridman, who is originally from Israel but lives in Madrid. It’s his first time working with an integrated cast, but he’s a rising star in the dance world. I’m not actually dancing in this piece, but I’m helping to manage it, so I’m very much involved. The piece has 10 dancers, five with disabilities and five without.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

I teach with Tali a training for integrated contact improvisation. The course is a full day once a week, and it’s a two-year program. Of course, it’s integrated for participants of all kinds of abilities. We’re trying to make the model co-teaching in an integrated team, one teacher with a disability and one without. That has a lot of power. This is our main practice for the past four years. We also do one-time projects and classes, like with a dance department in a high school together with the special education kids, or offering professional development for teachers in integrated dance so they have the tools to work with any kid.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

Many people think I’m joking, and then they see I’m not smiling. Usually I don’t have the energy to explain. Most people just have a question mark. Some ask, “With your wheelchair?”

When I teach, there are people in the class who at first don’t know I’m the teacher. I sense that they think I’m something exceptional but they still see dancing with me as an option. Maybe because the contact improvisation world is more open, dancing with someone with a disability is more of an option.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

When I go into a restaurant and there are stairs, I don’t get mad. I ask someone to help me up the stairs. I don’t have the energy to get angry. Of course I believe that integrated dance should be much more supported, and I hope that in the future we can teach anyone who wants to dance. I feel like I have two worlds; I really believe in this when I teach and present work, but when it’s personal, I find I’m not as involved. It’s more enjoyable not to be angry so much.

I’m not so interested in what people think about the choreographed work. There are so many opinions in the world. Some I believe; many I don’t believe. I’ve learned how to look at the creation process from my own point of view, from what I wish to see in dance or in film. For some, my films are slow and boring, but it’s something I like to see, like an endless shot where nothing happens. I like to see time as the value of discovery.

Maybe it’s different when I think about participants in my classes. There’s a variety of experiences within the same class. Some enjoy it, some not. I am giving a class though, which is different than giving a performance. I don’t give a performance for the audience. It’s more about creating beauty in the world. It doesn’t need to have relevance to others. But when I’m teaching, it matters to me what the students’ experience is. If I see someone suffering or having a hard time, I feel responsibility. But at the same time, I can accept that people don’t always enjoy my teaching. It’s fine.

As for the press, this new piece we’re working on has got me thinking a bit different than I was before. Before, I would have said to try and see it as professional dance. Now I think it’s more about the approach of the integration. In this new piece, Sharon is a bit brave. He is putting disability onstage and showing it as something weak and at the same time showing its power. He has managed to show these two qualities that actually everyone has. People with disabilities sometimes need more help. This is a reality and not something we need to hide or wrap in beauty.

For example, one of the dancers has cerebral palsy and walks with crutches. He can also walk without them but his balance is not good and he has a funny walk with short steps. In the piece, he walks without the crutches. It’s very powerful to see the weakness and difference, to see the naked walk without the crutches. The crutches hide the original walk. They not only help him physically, they also help to normalize him. But if he walks the way he does, without crutches, I can see it, feel it, and benefit from it. Appreciating this kind of detail is something different than what I thought before.

The press should understand that disability in dance isn’t something to portray as something that it’s not. Still, see it as a professional act. And of course, it should not be portrayed as charity or therapy.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

Of course not. Every studio, after school program, and university program should have the ability to accept anyone with any disability. But of course, there is a lot of work to be done. What happens sometimes is people open their doors to disabled students without the ability to teach them. You need the knowledge to understand how to work with a diversity of bodies and abilities before you open the doors. Many difficulties and frustrations can arise.

We need teacher trainings to start with. And then I would prioritize the schools. It should start from the beginning, even for students without disabilities to be open to this from a young age and see students with disabilities as participants.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

Yes, of course. It should be treated the same as other dance fields. It should be expected to be as good and as professional and be given the same space and recognition. Saying that, I’m not sure how I feel about integrated dance festivals. They can offer options that other festivals can’t. But at the same time, it can feel like a ghetto with an inner dialogue only within the community.

I would like to see good dance, period. If it’s integrated dance, then maybe I would be happier because I’m closer to it. But I would just love to see a good performance. I don’t want integrated dance to be promoted just because it’s integrated dance. It should be good. There’s still not enough good dance.

What is your preferred term for the field?

I’m really tired of dealing with terms. In Hebrew, it’s even worse; it’s much easier in English. In Hebrew, the word “disabled” is like an insult. I used to not answer when people used that word. Over the years I’ve gotten tired and now I use it myself and I don’t mind. Still, I agree there’s a lot of meaning behind the words we choose. At Power of Balance, we’re using “integrated,” but “inclusive” is also great. “People with diverse bodies” is also strong.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

Of course, yes. I think there are big steps. I can see development from our center in Israel and more support from the government. There’s still a long way to go, but it’s really different from what it was. There are more audiences and disabled participants who want to experience this.

Hai Cohen, photo courtesy the artist.

Image description: Hai is facing the back wall with outstretched arms. A standing dancer is behind him reaching toward him. Both of their shadows project on the wall.

~~

To learn more about Vertigo Power of Balance, visit vertigo.org.il/en/power-balance.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

This interview was conducted in April 2020.

~~

חי כהן: ״אני רוצה לראות מחול טוב, נקודה.״

מאת סילבה לאוקאנן; עריכה ע״י אמאלי ווידרהולט

חי כהן נולד בירושלים והפך למשותק מהחזה ומטה בעקבות קפיצה למים רדודים בבריכת שחיה. הוא היה עורך מוסיקלי בגלי צה״ל ולמד פילוסופיה. חי הוא בוגר בית הספר לקולנוע וטלויזיה ע״ש סם שפיגל והמשיך בעשיית סרטים תיעודיים. הוא רקדן, מורה ומנהל שותף יחד עם טלי ורטהיים את ורטיגו כח האיזון, הפועל בורטיגו כפר אמנות אקולוגי לא רחוק מירושלים. הוא מתרגל קונטקט אימפרוביזציה משנת 2000 ומנחה סדנאות ופרוייקטים לרקדנים עם וללא מגבלה, בישראל ובעולם.

~~

איך התחלת לרקוד ומה היו נקודות עיקריות בקריירת המחול שלך?

נפצעתי כשהייתי בן 13. קפצתי למים רדודים בבריכת שחיה. חזרתי למה שנקרא חיים נורמלים בתיכון. בישראל, יש לנו צבא, לכן, אחרי התיכון התנדבתי לצבא והייתי עורך מוסיקלי בתחנת הרדיו הצבאית. לאחר מכן למדתי קולנוע חמש שנים שלאחריהן עשיתי סרטים תיעודיים ווידאו נסיוני. בזמן תחקיר לסרט שעשיתי בשנת 2000, פגשתי רקדנית שהזמינה אותי לסדנת מחול משולב. אמרתי לא, זה לא מעניין אותי, אבל היא התעקשה ולבסוף הצטרפתי. הסדנה היתה דרך להקת המחול ורטיגו בהנחיית אדם בנג׳מין לקראת יצירה חדשה. הסדנה ארכה שלושה ימים והיתה מאוד חזקה עבורי.

לאחר הסדנה, אדם חזר לאנגליה ואז חזר שוב לישראל להתחיל לעבוד על היצירה. אחרי חודשיים שלושה של חזרות, ושנה אחרי הסדנה, ב 2001, העלנו את הפרימיירה של העבודה. ארבעה משתתפים עם מגבלה הצטרפו להרכב המקורי. שם העבודה היה ״כח האיזון״. הופענו איתה במשך שלוש שנים.

באותו הזמן, חקרתי קונטקט אימפרוביזציה עם טלי ורטהיים. רצינו לגלות כיצד אפשר להמשיך לרקוד מחול משולב בישראל. שנה מתחילת ההופעות של כח האיזון התחלתי ללמד. זו היתה תחילתו של ענף בלהקת המחול ורטיגו, גם בשם כח האיזון, שהוא מרכז למחול משולב לאנשים עם וללא מגבלה.

טלי ואני לימדנו סדנאות ויצרנו מספר עבודות לבמה, כולל דואט וטריו יחד עם רקדנית נוספת ללא מגבלה, מיה רשף. הטריו, ״11,711 מדרגות אבן בניקו״, היה אחד מהשיאים עבורי בגלל שהוא התבסס על הייקו. אני מנסה לבסס על הייקו כל דבר שאני נוגע בו. כשעבדתי בקולנוע, ניסיתי לייצר שירי הייקו קולנועיים, ובעבודה הזו ניסיתי לייצר מחול שמתבסס על הרוח והמבנה של הייקו, תוך שימוש בקונטקט אימפרוביזציה דוקא כצורה מקובעת.

אני גם חלק מעמותת הקונטקט אימפרו הישראלית שקיימת כבר הרבה מאוד שנים. אני חושב שהפסטיבל הראשון התקיים קרוב לזמן שהתחלתי לרקוד, ולאט לאט גדל במשך שמונה או תשע שנים. הוא מאוד חשוב לעבודה שלנו, שמכוונת לא רק לשדה המחול המשולב, אלא גם לשדה של קונטקט אימפרוביזציה בישראל ובעולם.

לגבי נקודות עיקריות נוספות, ב 2007, אלכס שמורק (רקדנית וחברה) ואני ייצרנו שיתוף פעולה עם להקה באתיופיה ליצירת כוריאוגרפיה ל״אדונייה״. אני גם עשיתי דוקומנטרי על הפרוייקט הזה. ב 2013, קיימנו שיתוף פעולה עם גרדה קניג ב ״הומזון״. כעת אנחנו באמצע תהליך חדש מאת הכוריאוגרף שרון פרידמן, במקור ישראלי, אבל חי במדריד. זו פעם ראשונה עבורו לעבוד עם הרכב משולב, אבל הוא כוכב עולה בעולם המחול. אני לא רוקד ביצירה הזו, אלא עוזר לנהל אותה, כך שאני מאוד מעורב. ביצירה הזו עשרה רקדנים, חמישה עם מגבלה וחמישה ללא.

כיצד היית מתאר את עיסוקך הנוכחי במחול?

אני מלמד עם טלי מסלול הכשרה לקונטקט אימפרוביזציה משולב. הקורס הוא יום מלא פעם בשבוע, וזוהי תכנית דו שנתית. כמובן, התכנית משולבת עבור משתתפים עם יכולות שונות. אנחנו מנסים לייצר מודל של הוראה משותפת בצוות משולב, מנחה אחד עם מגבלה ואחד ללא. יש לזה כח גדול. זו הפרקטיקה העיקרית שלנו בארבע שנים האחרונות. אנחנו גם עושים פרוייקטים חד פעמיים ושיעורים, לדוגמא שיתוף של מגמת מחול בתיכון יחד עם נוער מהחינוך המיוחד, או מציעים התפתחות מקצועית במחול משולב עבור מורים כך שיהיו להם כלים לעבוד עם כל ילד.

כשאתה מספר לאנשים שאתה רקדן, מה התגובות הנפוצות ביותר שאתה מקבל?

הרבה אנשים חושבים שאני צוחק, ואז הם רואים שאני לא מחייך. בדרך כלל אין לי כח להסביר. לרוב האנשים פשוט יש סימן שאלה. חלק שואלים, ״עם כיסא הגלגלים שלך?״

כשאני מלמד, יש אנשים בשיעור שבהתחלה לא יודעים שאני המורה. אני מרגיש שהם חושבים שאני יוצא דופן, אבל הם עדיין רואים את הריקוד איתי כאפשרות. אולי בגלל שעולם קונטקט האימפרוביזציה הוא פתוח יותר, ריקוד עם מישהו עם מגבלה יותר אפשרי.

מהן הדרכים בהן אנשים דנים בריקוד בכל הנוגע למגבלות שאתה מרגיש שיש להם השלכות או הנחות בעייתיות?

כשאני מגיע להכנס למסעדה, ויש שם מדרגות, אני לא מתעצבן. אני מבקש ממישהו לעזור לי לעלות במדרגות. אין לי כח להתעצבן. כמובן, אני מאמין שמחול משולב צריך לקבל הרבה יותר תמיכה, ואני מקווה שבעתיד נוכל ללמד כל אחד שרוצה לרקוד. אני מרגיש שיש לי שני עולמות; אני באמת מאמין בזה כשאני מלמד ומציג עבודות, אבל במישור אישי, אני מוצא שאני לא כל כך מעורב. זה מהנה יותר לא לכעוס כל כך.

אני לא מתעניין כל כך במה שאנשים חושבים על היצירה הכוריאוגרפית. יש כל כך הרבה דעות בעולם. לחלק אני מאמין; להרבה אני לא מאמין. למדתי איך להסתכל על תהליך היצירה מנקודת המבט האישית שלי, ממה שאני הייתי רוצה לראות במחול או בקולנוע. לחלק, הסרטים שלי איטיים ומשעממים, כמו שוטים אינסופיים ששום דבר לא קורה בהם, אבל זה משהו שאני מחבב לראות. אני אוהב לראות את הזמן כערך של גילוי.

אולי זה אחרת כשאני חושב על משתתפים בשיעורים שלי. יש מגוון של התנסויות בתוך אותו שיעור. חלק נהנים, חלק לא. למרות זאת, כשאני נותן שיעור זה אחרת מלתת הופעה. אני לא נותן הופעה עבור הקהל – זה יותר קשור ליצירת יופי בעולם, זה לא חייב להיות בהקשר לאחרים. אבל כשאני מלמד, זה משנה לי מהי החוויה של התלמידים. אם אני רואה מישהו סובל או מתקשה, אני מרגיש אחריות. אבל יחד עם זאת, אני יכול לקבל שלא תמיד אנשים יהנו מההוראה שלי. זה בסדר.

לגבי העיתונות, איזו עצה היית נותן לכתב שאינו מתמצא בכתיבה על אמני מחול עם מוגבלויות?

היצירה החדשה הזו שאנחנו עובדים עליה גרמה לי לחשוב קצת אחרת ממה שחשבתי קודם. לפני כן הייתי אומר לנסות ולראות בזה ריקוד מקצועי. עכשיו, אני חושב שזה קשור יותר לגישת האינטגרציה. ביצירה החדשה הזו שרון קצת אמיץ. הוא מעמיד על הבמה מוגבלות, מראה אותה כמשהו חלש ובו בזמן מראה את הכח שלה. הוא הצליח להראות את שתי התכונות הללו שלמעשה לכולם יש. אנשים עם מוגבלות לפעמים זקוקים לעזרה רבה יותר. זו מציאות ולא משהו שאנחנו צריכים להסתיר או לעטוף ביופי.

לדוגמא, לאחד הרקדנים יש שיתוק מוחין והוא הולך עם קביים. הוא יכול גם ללכת בלעדיהם, אך שיווי המשקל שלו לא טוב ויש לו הליכה מצחיקה עם צעדים קצרים. ביצירה הוא הולך בלי הקביים. זה מאוד עוצמתי לראות את החולשה וההבדל, לראות את ההליכה העירומה בלי הקביים. הקביים מסתירים את ההליכה המקורית. הם לא רק עוזרים לו פיזית; הם גם עוזרים לנרמל אותו. אבל אם הוא הולך כמו שהוא הולך, ללא קביים, אני יכול לראות את זה, להרגיש אותו ולהפיק מזה תועלת. הערכת פרט מסוג זה היא משהו שונה ממה שחשבתי קודם.

העיתונות צריכה להבין שמוגבלות במחול אינה דבר שאפשר להציג כמשהו שהיא לא. עדיין, לראות אותה כפעולה מקצועית. וכמובן, לא לתאר אותה כצדקה או כטיפול.

האם אתה מאמין שיש אפשרויות תרגול מתאימות לרקדנים עם מוגבלות? אם לא, באילו אזורים היית רוצה במיוחד לראות שיפור?

ברור שלא. לכל סטודיו, לכל חוג, ולכל תכנית אוניברסיטאית, צריכה להיות יכולת לקבל כל אדם עם מוגבלות כלשהי. אבל כמובן שיש הרבה עבודה. מה שקורה לפעמים הוא שאנשים פותחים את דלתותיהם לתלמידים עם מגבלה ללא יכולת ללמד אותם. אתה צריך את הידע כדי להבין כיצד לעבוד עם מגוון גופים ויכולות לפני שאתה פותח את הדלתות. קשיים רבים ותסכולים יכולים להיווצר.

אנו צריכים הדרכות מורים מלכתחילה. ואז הייתי מתעדף את בתי הספר. זה צריך להתחיל מההתחלה, גם עבור תלמידים ללא מוגבלות, להיות פתוחים לכך מגיל צעיר ולראות תלמידים עם מוגבלות כמשתתפים.

האם תרצה לראות מוגבלות בריקוד נטמעת במיינסטרים?

כן כמובן, צריך להתייחס אליה כמו לתחומי מחול אחרים. צריך לצפות ממנה שתהיה טובה ומקצועית, ולתת לה את אותו מרחב והכרה. אחרי שאמרתי את זה, אני לא בטוח מה אני מרגיש לגבי פסטיבלי מחול משולב. הם יכולים להציע אפשרויות שפסטיבלים אחרים אינם יכולים, אך יחד עם זאת, זה יכול להרגיש כמו גטו עם דיאלוג פנימי רק בתוך הקהילה.

הייתי רוצה לראות מחול טוב, נקודה. אם זה מחול משולב, אולי הייתי שמח יותר כי אני קרוב אליו יותר, אבל אני פשוט אשמח לראות הופעה טובה. אני לא רוצה שמחול משולב יקודם רק בגלל שזה מחול משולב. זה צריך להיות טוב. עדיין אין מספיק מחול טוב.

מה המונח המועדף עליך לתחום?

נמאס לי באמת להתמודד עם מונחים. בעברית זה אפילו יותר גרוע; זה הרבה יותר קל באנגלית. בעברית המילה “נכה” היא כמו עלבון. פעם לא עניתי כשאנשים השתמשו במילה הזו. לאורך השנים נמאס לי ועכשיו אני משתמש בזה בעצמי ולא אכפת לי. בכל זאת, אני מסכים שיש הרבה משמעות מאחורי המילים שאנחנו בוחרים. בכח האיזון אנחנו משתמשים ב”משולב”, אבל ”הכלה” זה גם נהדר. “אנשים עם גופים מגוונים” זה גם חזק.

מנקודת המבט שלך, האם התחום משתפר עם הזמן?

כמובן, כן. אני חושב שנעשים צעדים גדולים. אני יכול לראות התפתחות במרכז שלנו בישראל ויותר תמיכה מצד הממשלה. יש עוד דרך ארוכה, אבל זה ממש שונה ממה שהיה. ישנם יותר קהלים ומשתתפים עם מוגבלות שרוצים לחוות זאת.

~~