Hanna Cormick: “Not What My Body Does, But What My Body Is”

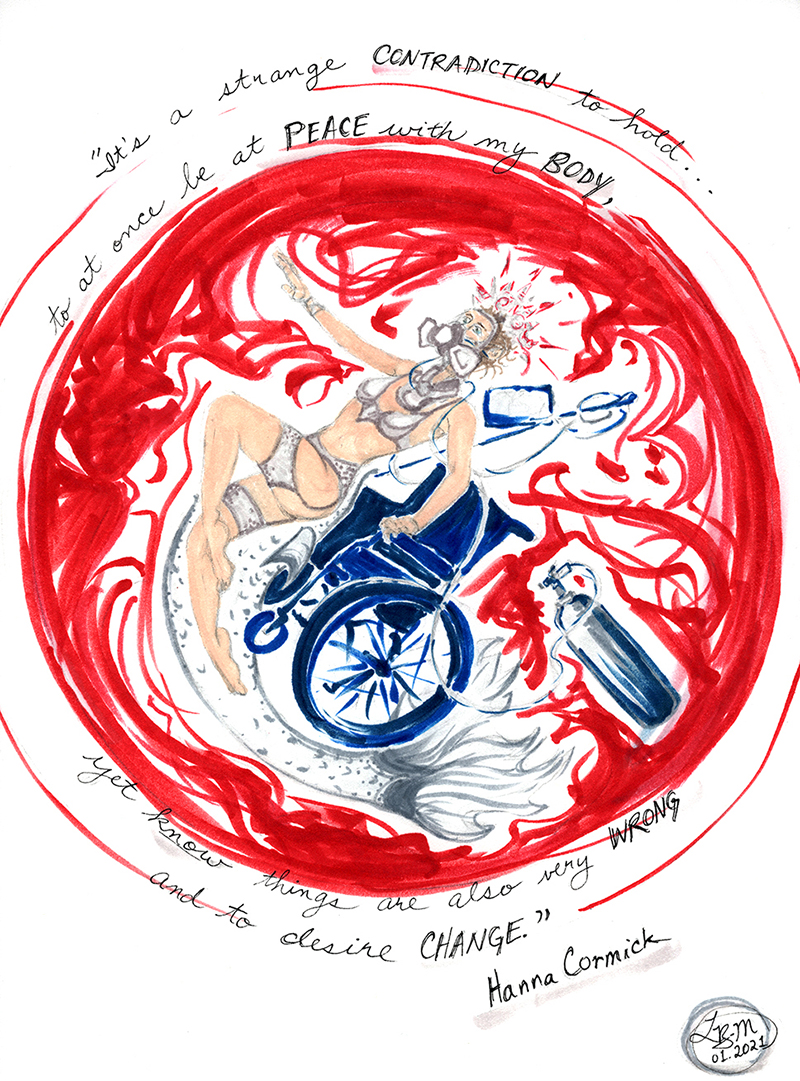

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Hanna Cormick is an Australian performance artist and curator with a background in physical theater, dance, circus, and interdisciplinary art. She is a graduate of Ecole Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris and Charles Sturt University’s Acting degree in Australia. Hanna’s practice has spanned many genres and continents over 20 years, including as a founding member of Australian interdisciplinary art-science group Last Man to Die, one half of Parisian cirque-cabaret duo Les Douleurs Exquises, and as a mask artist in France and Indonesia. Her current practice is a reclamation of body through radical visibility.

Listen to the audobook recording of Hannah Cormick’s interview here!

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book, visit here!

Image description: Hanna is depicted as if she is emerging from a blue wheelchair wearing gray burlesque attire with her breathing apparatus and oxygen tank attached. She is enclosed within a red sphere of energy with the quote, “It’s a strange contradiction to hold…to at once be at peace with my body, yet know things are also very wrong and to desire change.”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

My work exists as acts or embodiments. I don’t always use the word “dance,” as my work doesn’t stay inside the conventional boundaries of what that label generally refers to. I did, however, have a fairly traditional dance formation: ballet, jazz, tap, contemporary, as well as belly dance and tango. Growing up with undiagnosed hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome meant that I could do intensely flexible things with my body. This natural facility later led me to train as a circus contortionist. Back when I was young, it proved an asset.

My practice has always flowed across seemingly disparate styles, often pushing boundaries: butoh and Artaud, audience-interactive and site-specific experiments, or, with my company, Last Man to Die, exploring the interactions between the movements of my body and other artforms – computer percussion, interactive projected visuals – through the use of novel technology and artificial intelligence.

For a long time, mask was my obsession, both as a performer and as a mask-maker. I loved the total connection to the body and the intensity of the somatic trance-like experiences, as well as the physicality of carving wood and molding leather. A highlight was a year travelling between Bali and Australia apprenticing with the island’s foremost mask-maker/dancer, Ida Bagus Anom. I continued with my mask practice by moving to Paris to study at Ecole Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq and apprenticed with Commedia master mask-maker Stefano Perocco di Meduna.

Mask was the impetus for training in Paris, but I slowly fell out of love with the form. I shifted towards forms influenced by my time with Ecole Lecoq, the Grotowski Center, and other experimental practitioners. I also trained in circus arts, delving into the underground cirque cabaret scene with my collaborator Apollo Garcia, specializing in La Danse Apache, where we mixed dance forms like tango and the Charleston with circus skills, including stage combat, acrobatics, and contortion. We spent time clowning with the Sirkhane Social Circus School on the Turkish-Syrian border with young Syrian and Yazidi refugees.

In 2015, my practice changed dramatically when I became disabled. I have a trifecta of genetic disorders: Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Mast Cell Activation Syndrome, and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. These cause many secondary issues such as spinal instability, seizures, dystonia, and episodic paralysis. I’m a wheelchair-user now, and my immune system behaves as if it’s allergic to everything: the odor of food, fragrance, chemicals, sunlight, and much more. I now live inside an air-sealed room. I can’t be around most people and I can’t go outside.

As a result of these restrictions, and the way in which my performance practice has evolved to accommodate them, my work now aligns more closely with live art or performance art. My coming out as a disabled performer was The Mermaid, performed over 2018 and remounted at the 2020 Sydney Festival. The piece was a physical representation of the social model of disability. In water, a mermaid can move freely, but on land she presents as disabled. Dressed as a mermaid, I was supported by my mobility aids and medical protective equipment: wheelchair, orthoses, splints, respirator mask, oxygen tank, and IV drip. Sharing the same physical space as the audience meant that I was exposed to the pollutants they brought into the space – chemicals, fragrance, bacteria – and that the performance could be interrupted at any point by allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, seizures, or paralysis. The piece used my body as a microcosmic model of the environmental destruction we have wrought upon the planet through our actions. The fossil-fuels in an audience member’s perfume would send my body into a dystonic storm or respiratory distress, just as the country was being assailed by bushfires triggered by fossil-fuel impacts on climate.

My performance works have been a practice in confronting shame and developing pride in disability, though I still encounter internalized ableism. Part of crip politics is to reject the notion of a cure, but when it comes to chronic illness, of course I would want to be cured. It’s a strange contradiction to hold within myself; to at once be at peace with my body, yet know things are also very wrong and to desire change.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

It can be difficult to describe my practice to those who come from an arts culture in which “practice” is defined as productivity, repetition, and routine. I make space for Crip Time and non-extractivist modes of making: deceleration, pausing, irregularity, unreliability, and the radical levels of flexibility and responsiveness that are required to work with those values. Time doesn’t exist in the same way when you are chronically ill; I don’t have reliable day-to-day systems. I have limited amounts of energy, so I must be constantly aware of how much energy it takes for me to do something. Because it’s highly destructive if I attempt to push through to get things done, I’m always measuring and monitoring. There are periods when I’m able to do more and other periods when I literally cannot move. My body calls the shots, not my will-force.

My work is no longer about what my body produces; it’s not what my body does, but what my body is. My body’s inabilities or lack of agency, its rebellious uncontrolled aspects, the conflict between a space and my body, all become choreographically relevant. It centers how I am moved by the space instead of how I move within it, as if I’m being danced by the environment and my body is a stage through which the dance passes.

It’s a deeply disquieting sensation to let the moments in which I don’t have control of my body – dystonia, seizures, paralysis – become public spectacle, but it’s also empowering. These are the daily things that happen to me, and turning them into something that has artistic and political relevance reclaims these experiences from the dehumanized pathologized world of the medical, so they can come to mean more than the futility of invisible suffering.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

My immunological disability is the one people tend to focus on, rather than the physical barriers I face. For most people, the idea of living inside a bubble is so curious that they skip from, “She’s in a wheelchair; how can she dance?” to, “She can’t breathe normal air; how can she live?”

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

The narrative of overcoming is really prevalent. On the one hand, there’s a focus on the seeming insurmountability of my barriers with people using terms to describe me like “confined,” “wheelchair bound,” and “tragic.” On the other hand, there’s the use of words like “brave,” “strong,” and “fighter.” I am uncomfortable with both, but particularly this language that glorifies strength and bravery. I am weak, my body is fragile, but are those necessarily bad things? Something I explore is the possibility of being fragile and still being a worthy artist, a worthy human.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

As someone who had professional training and a career before I became disabled, I’m aware of the privilege of having had that doorway into the industry. For people who either acquired their disability earlier in life or were born with a disability, it is much harder. I would like to see training programs that are accessible to disabled artists within institutions, and workshops that are accessible to people with atypical access requirements.

A lot of workshops are not accessible for someone with an immunological disability, and it’s often considered outside the realm of access to have guidelines on the pollutants brought into a space – fragrance, makeup, food, drink – even though there may be strict guidelines on the types of footwear or clothing used.

I’m exploring how to transpose the Lecoq pedagogy for wheelchair-using bodies. The teachings of Lecoq are an integral part of my artistic psyche, but it now feels inaccessible to me since so much of the pedagogy is based around the idea of a neutral body. When you look at the body through this frame, any deviation from “neutral” becomes something that is being communicated. If you’re using a mobility aid, your body is communicating disability. What if we instead viewed a wheelchair-using body, or other crip bodies, as their own forms of neutral? I want to reconcile my training with my new body, as well as make the pedagogy, which is a valuable creative framework, accessible for people who don’t have a Lecoq-normative body.

Since the coronavirus, there has been an explosion of virtual dance spaces. On the one hand, it’s great. This is access that people who are house-bound, bed-bound, or immunologically impaired have spent years fighting for. I’m excited by how the disability community has led innovation by drawing from pre-existing access tools, like creative audio description, to provide new ways of experiencing dance remotely. On the other hand, access to the virtual realm can be precarious for many disabled people, so it isn’t a panacea.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

Disability performance should, as a genre, retain its own identity. When working in spaces that are specifically designed for disabled people and where everyone has an impairment, there’s a certain freedom and ease of communication. But I believe mainstream dance should be accessible for disabled dancers as well, and disabled dancers, choreographers, and companies should be viewed as part of dance culture as a whole. I’d love to see dancers with disabilities get hired, not as a tokenistic gesture, but because we as artists bring something vibrant and unique.

What is your preferred term for the field?

I identify as “crip,” which is a historic slur being politically reclaimed by a subset of the disability community. I would be comfortable with a non-disabled person referring to me that way, especially if they had checked about my preferred terms. But it is not an identifier one should externally place onto others without knowing if it is preferred, as some still receive it as an insult. If I was self-describing my work, I might refer to it as “crip performance,” but if I was working with others, I might use a more widely used term like “disability dance.”

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

To me, it seems like a sudden bloom or renaissance but that might be because I’ve only been working as a disabled artist for a few years. When I first became disabled, I wasn’t aware of the crip arts community. It has been exciting to discover subversive and bold performers creating works that are fascinating, moving, and politically provocative.

It feels like opportunities in the mainstream are improving. In the past year or two, there are more disabled performers in large arts festivals and more celebrities identifying as disabled or chronically ill, which reduces the stigma. I hope even more barriers will be removed as representation grows and culture shifts, so we can start to see true cultural equity.

Photo by Shelly Higgs, Novel Photographic

Image description: Hanna is pictured in her blue and pink mermaid costume sitting in her wheelchair with her breathing apparatus. Behind her is a concrete wall and window.

~~

To learn more, visit www.hannacormick.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

This interview was originally conducted in April 2020.