Tabled: Labor and a Living Wage

TRANSCRIBED BY COURTNEY KING, EDITED BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Tabled, a project by Chlo & Co Dance, takes what has been set aside – “tabled” – and brings it into conversation. The series ran from March through December 2021. The panel “Labor and a Living Wage” was held on June 1, 2021 via Zoom and featured San Francisco-based dance artist Emily Hansel, New York City-based storyteller and photographer Steven Jones, and Connecticut-based artist and arts administrator Malakhi Eason (also known as Dr. Kreative). This transcribed and edited version seeks to continue the conversation.

Questions for panelists:

- As an employee, what standards do you have when making compensation decisions?

- How does this affect your role as an employer?

- How can financial viability be improved and maintained in the arts?

~~

Malakhi Eason: I’ve been working in the arts administration field for about 15 years. I’m currently the director of programming and community impact for the International Festival of Arts and Ideas.

Steven Jones: I’m a photographer. I’m also a sixth-year PhD candidate at Rutgers University. I’m about to be a professor at William Patterson University as well. I’m also the editor and founder of Late Fee magazine, a small magazine that I created to highlight and showcase artists of color.

Emily Hansel: I work as a dancer, choreographer, and arts administrator for dance organizations, and a dance teacher for young children. I like to say I’m an artist advocate or a dancer advocate. I do a lot of work with Dance Artists’ National Collective, a national group of working dancers focusing mainly on labor and wage issues for our freelancer community.

Malakhi: The first question is, “What standards do you have when making compensation decisions?”

I’ll start with a personal story. When I started working in this field, I basically was like, “I’ll take anything to be in this organization.” At that time, I was working a job where I was getting paid less than I was offered, but for me, it was a worthy sacrifice, and I really wanted to work in that field. But as I was going forward in my career, I realized I was getting paid less than those on the same level as me. I talked to one of my mentors and shared that I was struggling, unable to pay my rent, I have a son, and I was extremely stressed about the amount of work I was putting in and the amount of pay I was getting back. It’s always a sensitive topic to talk about. You’re scared you’re going to lose your position. But what I’ve learned over the years is that you have to believe in yourself before anybody else believes in you. I had to believe my work was worth it. I remember the day I went into the HR department. I went with a speech written out because I like to be calculated, but I ended up just speaking from my heart. The HR director said, “We don’t necessarily have the means at this moment, but we really value your work.” I appreciated her being transparent with me, but nothing was set after that, so I had to go back again and put my foot down. When I fought for it, I felt like she knew I was not playing. We had a conversation about what a pay raise increase could look like. It’s hard to fight for yourself because you’re always fearful of losing. But once you put your worth out there and people recognize that, they value you.

Emily: Oftentimes I don’t acknowledge my full worth. When I graduated college and started out, I did a lot of work pretty much for free. Then slowly, more opportunities came with slightly higher rates. I’m five years into my professional career, but I’ve recently hit a milestone where I was able to say no to someone who offered me a job. It was mostly because the pay rate was so low. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the guts to explicitly say, “I can’t do it because that’s too low for me.” I find myself needing to smooth over the reason. I’m challenging myself moving forward to be honest if I’m saying no because it’s a low wage or stipend.

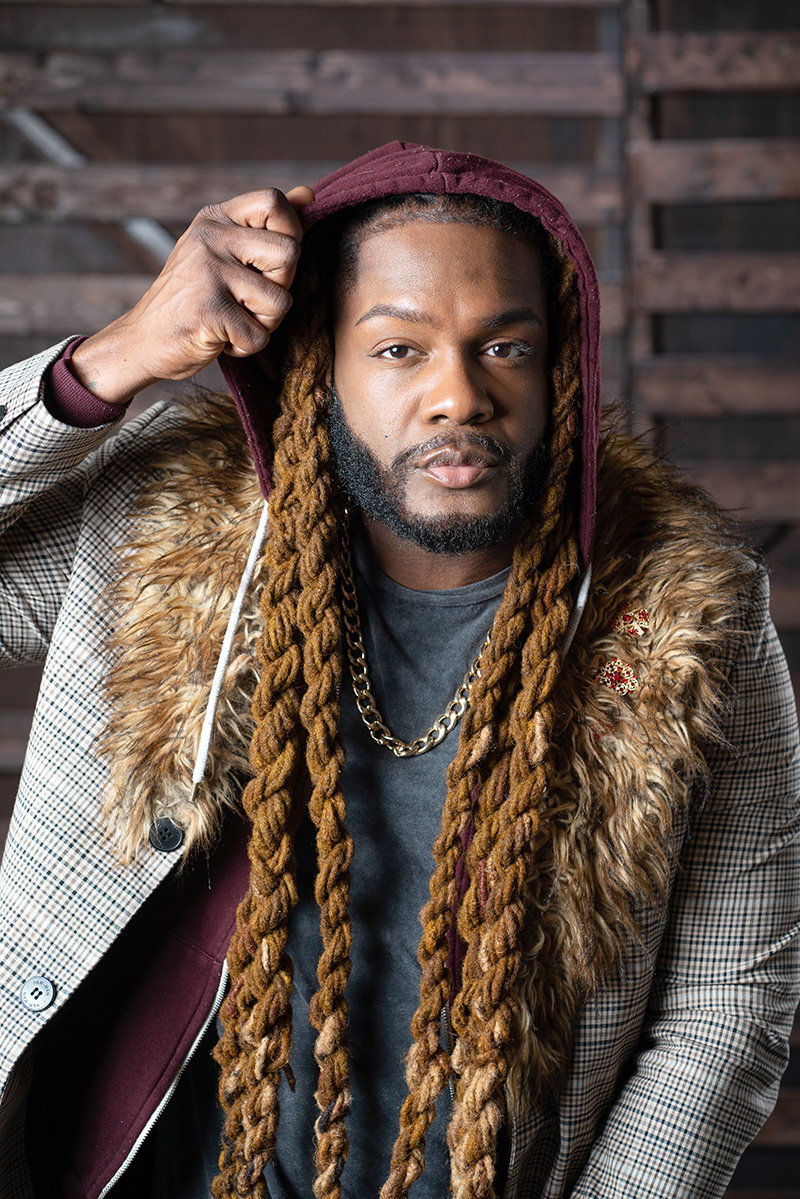

Malakhi Eason, Photo by Perry Tayor for Uncanny Photography

Steven: I totally agree about knowing your worth. For me, in the beginning, it was just about balancing: trying to learn, trying to gain access. I may not have been getting paid, but was I gaining experience? But then eventually you have to know your worth because people will abuse your talents. As an employee, I like transparency and fairness on both sides, like, “Hey, I know what I’m worth. Can you provide for that?” If they can’t, be transparent enough to tell me and then let me make that decision. Especially when you’re starting out with your art, you have to get experience, but you also have to know your worth, and every time you do your art, you get better, and your value goes up.

Malakhi: As a singer, I had to learn how to just say no. I have history and experience. If you’re not able to pay this rate, I don’t need to do it. I don’t care if I’m struggling. Once I allowed myself to be devalued when I know that I am worth a whole lot more, then that’s going to become regular. I may end up negotiating a lower price. Do you ever get in that place where you feel like you know you’re selling yourself short?

Steven: I used to until I became aware that I was doing it. One of the things I do now is send invoices with the full price, and then I’ll mark down the discount from what it is, as if to say, “This is my worth, but I’m doing you a favor because I love you as a friend or I love you as an organization.” I try to save my good favors for close friends and organizations I really love and want to help.

Emily: I have 10 to 15 different part-time freelance jobs at any given time. Some are performing, some are teaching, and some are admin. The jobs that pay me the most are the teaching jobs by far. I used to always say I never want to be a teacher. I never wanted to have that much influence over a young mind, but I’ve learned to love it.

Malakhi: What are our standards when making those compensation decisions? For me, it’s important that everything’s in writing, as well as doing my research: the amount of work that I’ll be doing, what other people are getting paid, the company’s history, the company’s pay history. Doing the research helps when you’re making those negotiations.

Steven: In the beginning of my career, contracts and invoices weren’t a thing because we’re very relational as artists. But then, stuff happens even with friends. So that’s a good point you made about the contract because that’s the binding thing. Even with my students, I say, “This is a syllabus. This is our contract. Hold me to it.” Sometimes it feels like you’re hurting the relationship by bringing up money and contracts, but you’re doing it for your livelihood.

Steven Jones, photo by @freakovasquez

Emily: I have three standards, and I have broken all of them. I want there to be a written agreement. I want to be paid as an employee instead of as a contractor. And I want to get paid $30 an hour or more as a dancer. Right now, I dance for someone with whom we don’t have a written agreement, I dance for plenty of people who pay me less than $30 an hour, and I dance for plenty of people who pay me as a contractor instead of as an employee. These are my standards, but I know not everyone who’s hiring me can accommodate. Whenever any of those standards aren’t there, that’s when I consider: What am I getting? What can I give up? I assess the sacrifice.

Malakhi: Can you talk about the difference between being a contractor and an employee?

Emily: I made this standard for myself recently because of the California law AB5. The benefits of being an employee play out in the amount of taxes I have to pay. Contractors pay roughly 15 percent of their contracted income. As an employee, I pay half of that and my employer pays half of that. There are more expenses you can deduct as a contractor versus as an employee, but I’ve calculated, and I save a lot more money by being an employee. The other benefits are workers comp, which is huge for dancers, as well as accumulating sick pay, worker protections, and minimum wage.

Malakhi: The next question is, “How does this affect your role as an employer?”

Emily: I can jump right back in because it’s the same three standards. I am not currently an employer, but I intend to be soon. I have been planning this for a few years. I used to choreograph informally on close colleagues and friends and pay people a small amount. But I took a few years off, saved money, and this fall/winter, I’m going to become an employer. I’m going to pay dancers $30 an hour. And I’m going to make a thorough written agreement with them. It’s going to be a short project because I’m testing it out and because it is going to be really expensive. Ask me a year from now, and I hope to have more answers on if this is viable, but I’m trying hard to practice what I preach.

Steven: In the beginning for me, it was a lot of trade for print. But now, before I even start a project, I try to save money so I can hire people. Sometimes as artists we have ideas, and we want to get these ideas out. But people need to eat. If you focus on the project and not the people, that can be very detrimental. If you’re in a position to pay people, you should try. That’s where transparency comes in. Sometimes you can’t pay people. I’ve had friends pay me months after a project. I try to remember that when I hire people or ask people to do favors, because you can always pay your friends later.

Malakhi: Let’s try to hit the last question, “How can financial viability be improved and maintained in the arts?”

Emily: If you can’t make a living wage being an artist, then it’s not a viable career option except for those who have access to other wealth or other sources of income.

Malakhi: How we can improve it is by conversations like this, as well as talking to executive directors, board members, and donors.

Steven: I think we also need to create strong communities of artists who will stand up and fight for each other. Without the artist, there’s no art. How do we fight that fight together?

Audience question: Relative to dance, do rehearsal hours, tech rehearsals, and performance dates need to be a part of contracts?

Emily: Here’s an example. Let’s say we’re rehearsing on and off multiple days a week. Maybe it’s a year-long process. There are upcoming rehearsals, but we don’t know exactly when those will be yet. That’s fine, but it does need to be accounted for. Maybe there’s a line that says the January rehearsal schedule will be distributed by December 1st.

Audience question: COVID has been an interesting time for a lot of reasons. One thing that happened with a company that I was working with is the show was supposed to be this summer, and then it was supposed to be this fall, and now it’s in January. It’s been tricky to recommit to a somewhat unknown schedule continually. As someone who’s also a director, proactively checking in with people is important. COVID has been so wild, and being asked to commit to moving targets is tricky. Make sure you have the opportunity to regularly communicate in your contract.

The other thing I want to share is I have a job in the corporate world in addition to dance stuff. The idea of not negotiating my salary or starting work without a contract is a joke. I would never do that. One of the things I think about when I negotiate my salary or ask for a raise or promotion is this idea of taking the emotion out of money. I don’t mean to be insensitive about it, but I think sometimes we get so nervous as artists asking for more pay because it feels so emotional, but you really have to step back. I need to ask for what works for me, and I’m not going to let myself go down the slippery road of having a breakdown about what’s going to happen if I ask for what I feel like I deserve.

Emily: Removing the emotion from negotiating is something I’ve recently heard a lot about and not actually practiced yet, but that’s so key. My apartment costs this much, my food costs this much, my healthcare costs this much. Divide that by the number of hours I might work in a week. Can I afford to be there for the amount they’re paying me? It’s not emotional. It’s math.

Audience question: This isn’t so much a question. I work with Emily, and in those moments where she has spoken up are so impactful because, as dancers, we’re often conditioned to be grateful. To have my peer and colleague speak up about that is so empowering.

This whole conversation feels linked to utilizing the privilege we have, and when we do this actively and with empathy, it’s also an anti-racist force. It’s really empowering to have these conversations with one another because then we can move forward as a group as opposed to feeling like individuals.

Emily: Thank you for saying that. I’m just copying the people whom I admired before me.

Emily Hansel, Photo by Tricia Cronin courtesy of Post Ballet

~~

To learn more, visit www.chlocodance.com/tabled.

2 Responses to “Tabled: Labor and a Living Wage”

Absolutely, Nikhita! Thanks for reading and sharing!

Great conversation, so relevant!

wish my fellow Namibian artists will read this once I share it.

I had to learn all of this by doing, but my peers are not so confident to own their craft, they are more hungry than anything to accept whatever comes their way. It is important to have professional boundaries as artists, but it really isn´t the easiest when you have nothing else bringing in an income.

Comments are closed.