Preserving Street and Club Dance Culture by Many Means

An Interview with Tatiana Desardouin of Passion Fruit Dance Company

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Tatiana Desardouin is the director and choreographer of Passion Fruit Dance Company, a street dance theater and educational company based in New York City. With a mission of addressing social issues like racism and striving to inspire young artists to share their voices, Tatiana has structured Passion Fruit to include performances, teaching programs designed to provide tools to heal and build confidence, and multisensory experiences within a cultural party called Les 5 Sens designed to build bridges. Here, Tatiana describes the different facets of her company and how all her work revolves around preserving the authenticity of street and club dance culture, and therefore Black culture.

(L-R) Lauriane Ogay, Tatiana Desardouin, and Mai Lê Hô, Photo by Loreto Jamlig

~~

Can you tell me a little about your own dance history – what shaped who you are today?

I was born and raised in Geneva, Switzerland. Both my parents are Haitian. My relationship with the United States and specifically with New York City is through family; I’ve been coming here since I was 18 months old for vacation every summer. That’s also how my relationship with street and club dance culture started. I was coming to the Bronx a lot and learning about social dances.

I grew up in a Haitian nonprofit where I had my first performance experiences doing Afro-Haitian dance. Within that same community, I started doing hip-hop, but it was very informal. There were no teachers. We were dancing based on what we saw in videos. Back then, the music videos were more authentic, less commercial, and you could see the culture and influence in the videos.

In 2002, I discovered house dance in a workshop with Brian Green. Hip-hop was already well spread in Europe, but house wasn’t really. To understand the culture more, I came to New York in 2005 to study. House isn’t the type of dance you really learn in the classroom, nor is hip-hop. You learn it socially in its cultural environment, like for instance the clubs.

So I started with hip-hop and then did other dance forms within the street and club dance umbrella, specifically house and funk styles such as popping and locking. From there, I traveled a lot in Europe to cypher and enter jams and competitions. Through all that social engagement, I built my dance and eventually took workshops with people from New York and the West Coast. That’s how I got to know the styles and vocabulary.

I opened a dance school in 2012 in Geneva called Le Centre Hip-Hop, as well as my first company called Continuum with four choreographers. That was the first street dance company in the French side of Switzerland. I’m very involved in the street dance community, and I invest a lot in the youth. Teaching, doing nonprofit work, organizing parties, battles, sessions, conferences, all of it shaped me.

I moved to New York in 2016 because I wasn’t growing enough artistically. Switzerland is a very comfortable place. New York is where hip-hop culture was born, and it also better represents me as a Black woman. In Switzerland, it was difficult because of their lack of support for dance and lack of understanding of Black culture. What I do is not taken seriously. Here I can celebrate my Blackness more than in Switzerland.

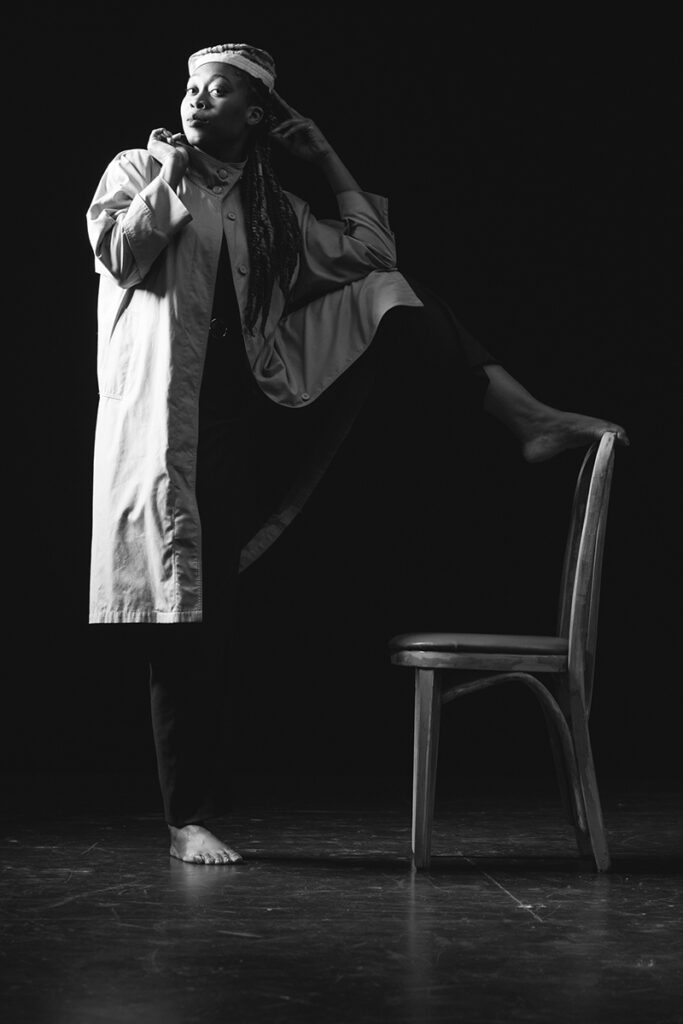

Tatiana Desardouin, Photo by Lauriane Ogay

How did Passion Fruit Dance Company come about?

It was a combination of all my past experiences as a teacher, mentor, and choreographer. I wanted to do something that represented my values, and I didn’t want it to only be about performance. There’s a lot of social justice involved in Passion Fruit, and it emerged from my personal frustrations with the European scene and a lack of understanding of the Black culture. There was the lack of understanding the groove. It was seen as an option for dancers, but for me it’s the essence of street and club dance. People see it as an aesthetic, so then it becomes a choice. But if people understand it as the core essence of the culture, it’s no longer a choice.

That comes from a lack of understanding about why Black dances in US exist. People know where the dance was born, when, who created it, but not why. Once you understand that the “why” creates the aesthetic (a groove that looks different on each body) and that the groove is the physical representation of Black people’s living experience (pain and joy), then the groove is no longer disposable in the dance. The why is slavery. If there wasn’t slavery, there’d basically be no Black culture in the shapes and forms as we know it in America. There’s a direct connection. Hip-hop emerged as a way of protest. It wasn’t a formal protest. People just started to react in their everyday life to what was happening in the Bronx. From there, people started to create this whole culture. They were kids, so they weren’t aware of the power of what they were doing. It came out of other Black movements, like jazz, which was also a protest movement by Black people.

For me, it’s important as a participant of this culture to make sure there’s an understanding of who we are, what we’ve done, what our impact has been, and how it needs to change when it comes to systemic racism. I like to do it through art; this is my lane. So I created Passion Fruit, which has performances, educational programs, and events. All of these are linked together.

From the performance side, how is Passion Fruit Dance Company organized?

The three core members are me, Lauriane Ogay, who is also from Switzerland, and Mai Lê Hô, who is French and Vietnamese. We know each other from the European hip-hop scene. They both moved to New York before me. Those were the dancers who I felt most comfortable with to create, and they understood the conversation about race. They were the first non-Black people I could have open conversations with. In Europe, we (as Black people) were really censored. It’s not like over here. In the US, it’s in your face. In Switzerland, they love to pretend that racism is non-existent. It was extremely difficult to develop a vocabulary to talk about it.

I decided to create this piece called Dance Within Your Dance, where the theme is the groove. It’s an invitation to understand what it is, and from there we can get to the conversation. That was my way of being an activist through dance. It’s not just about the piece. It’s about the piece plus the conversation. It’s a way to connect and raise awareness.

My latest piece, Trapped, we did at the Guggenheim. I worked with three additional dancers who are dear friends. I wanted to work with mature women – the youngest is 30 and the oldest is 40. I wanted women who were comfortable opening up about their own blockages and personal experiences with the audience. It didn’t have to be literal necessarily, they could share the way they want, but I wanted them to highlight what we’re going through collectively and individually so other women could recognize themselves and hopefully find tools of healing through it.

(L-R) Nubian Néné, LaTasha Barnes, Mai Lê Hô, Tatiana Desardouin, Gyeun “Soo” Jeong and Lauriane Ogay with music produced by Saadiq “the last musician” Bolden, Photo by Loreto Jamlig

Can you share a little about your choreographic process?

Everything I do is something that needs to be understood deeply by the people I dance with. I make sure they understand what I want to share, and I try to see if they align with my vision. It’s not like I just take a good dancer. I take someone who deeply believes in the values. It makes the process easier so when we have a talk-back or Q&A with audiences, we can share a specific message.

I think about the structure and each section of the piece in advance. I write it down. Sometimes I do vision boards. I put phrases of words or themes I want to express. When I arrive to rehearsal with the dancers, that’s when I create movement. I never pre-create movement. I’m more efficient on the spot if I have the music and get inspired.

In what kinds of venues and for what kinds of audiences does Passion Fruit usually perform?

We’ve been blessed to perform in theaters and festivals, both indoors and outdoors. We’ve performed in small theaters to bigger ones, like Jacob’s Pillow, New Victory Theater, the Guggenheim, and Dance Place in Washington DC.

The challenge I have is authenticity for the specific reason of keeping the lineage alive and making sure there is no more erasure. We need preservation. The dance we do is codependent on the people and the culture. It’s never independent. By me dancing it onstage, I remove it from its original space of expression. The challenge is that it is no longer authentic once I put it in a theater. It’s a social dance, not a concert dance.

The authenticity lies in the people who are the vessel of this culture. We can keep it alive through our bodies. By being part of this culture, that’s where the authenticity lies, through our experiences in this culture and our bodies, especially the bodies of African descent.

Sometimes contemporary dancers are interested in using hip-hop movements, and they call it “contemporary street” or something. For me, it doesn’t make sense. It’s beyond learning the dance for two or three years and then performing it onstage. That doesn’t represent us. People want to perceive dance in a Euro-centric way, meaning you see it movement for movement. But our movement is a folklore. It’s culture. It’s never separated. It’s our Afro-centric vision. In the arts and theater world, people look at us through a Euro-centric lens. Unfortunately, the audience is mostly non-Black for many reasons – it’s unaffordable. Even for me, it’s not so accessible. If we have to perform mostly in front of non-Black people, let’s use that platform to educate people about us and build bridges.

(L-R) Mai Lê Hô, Tatiana Desardouin, and Lauriane Ogay, Photo by Loreto Jamlig

What is the Passion Fruit Seeds teaching program and how is it structured?

Passion Fruit Seeds is the umbrella of many different programs. There’s one called Hip-Hop Culture, Its Foundations and Its Uprooting. This one was recently made through the City of Geneva, but it was online and open to the world. It was basically an anti-racist six-day training where people got to understand the relationship between Europe and the US when it comes to systemic racism. In Europe, people tend to think it’s just a US problem. It’s definitely physically more violent here, but in Europe, the violence takes different shapes and forms. It was important to me coming from Switzerland that people understand it’s happening there as well. I had a teacher from the University of Southern California, Moncell Durden, who is a historian of street dance, music, and Black culture, as well as a Noémi Michel, who is a teacher of post-colonial history in Switzerland and Europe. In addition to those two specialists, me, Mai Lê, and Lauriane did the arts engagement. People could learn historical facts and connect the dots to art. It was important to find a way for people to do introspection and learn how they can make change.

Another program was called Focus on Black Excellence. Again, all the teachers I brought in were from the African diaspora so people could learn from a Black perspective. A lot of students aren’t used to learning from Black people. I wanted to push this idea and, specifically for the Black kids, create a network for them: Here are people doing great things that you can connect to and reach out to if you need.

Then there was Focus on the Youth, which was the first program we did at the Yerbabruja Arts Center in Long Island City. The center is for the Latinx community in an area where the MS13 gang is centered. There’s a lot of trauma; some of the kids had been initiated and some of them had lost their friends. But the environment we created was super positive. The Yerbabruja Center makes them learn many different dances from South America. Then they got to learn hip-hop and house from us. It was a program to empower them to understand that their people created the cultures we brought in. I think that stayed with them. They said, “Wow, we created that?” The problem was the kids weren’t really dreaming. As they matured, it was difficult to project themselves into the future.

So Passion Fruit Seeds has many different ways to bring tools for wellness and healing processes, and also elements of anti-racism.

Can you share more about “Les 5 Sens” multisensory experience?

“Les 5 Sens” – meaning “the five senses” in French – started in Switzerland, but the inspiration was New York. I went to a lot of parties that were multi-disciplinary events with dancers, musicians, and live painting. In Geneva, the arts scene is very scattered and disconnected. I wanted to create an event where different ages, cultures, and art forms could come together and experience their senses, which is what we experience in general, but I wanted to push that deeper. Each hour there was a different smell in the room. The theme for the sense of taste was “Sweet, Salty, and Spicy,” so imagine a club with free bites everywhere. There were also different performance happenings, fashion, painting, and people from the community selling their stuff. It was a very community-based event. I had friends traveling from different countries because they wanted to support and perform. The idea was to bring people to our community. We’re often asked to go perform in other places. I wanted people to come to our underground scene. It’s about building bridges. I did the event twice in Geneva before I moved and twice in the United States, but we haven’t had the chance to do it again. I want it to be ongoing, but I’m focusing on Passion Fruit Seeds and performances for now.

What’s your next project or focus?

I shared about our new piece called Trapped about women revealing their blocks to heal, and now I want to make it longer to be an evening-length piece. I’m looking for residencies and have some possible opportunities coming up. Next year, we have a residency for a new piece called Dimensions, which is a partnership with my dancer Lauriane, who is also an amazing photographer. We want to create a multidisciplinary piece based on her photos to be performed in museums with dance, visuals, and videos.

Tatiana Desardouin (left), Lauriane Ogay (top right), and Mai Lê Hô (bottom right), Photos by Lauriane Ogay

Any other thoughts?

Passion Fruit in general wants to offer an example of how we use our art to preserve our culture by any means necessary. Yes, we could do it only through performances, but we choose to do it also through education and events. We want to be an example of what impact you can have using what you do. There’s a way to do it that doesn’t always feel so heavy. I think that’s something people hear a lot about social justice work, the heaviness. I still have fun creating as well as working toward the greater good.

~~

To learn more, visit www.passionfruitseeds.com as well as on Instagram @tatianadesardouin or @passionfruitdanceco.