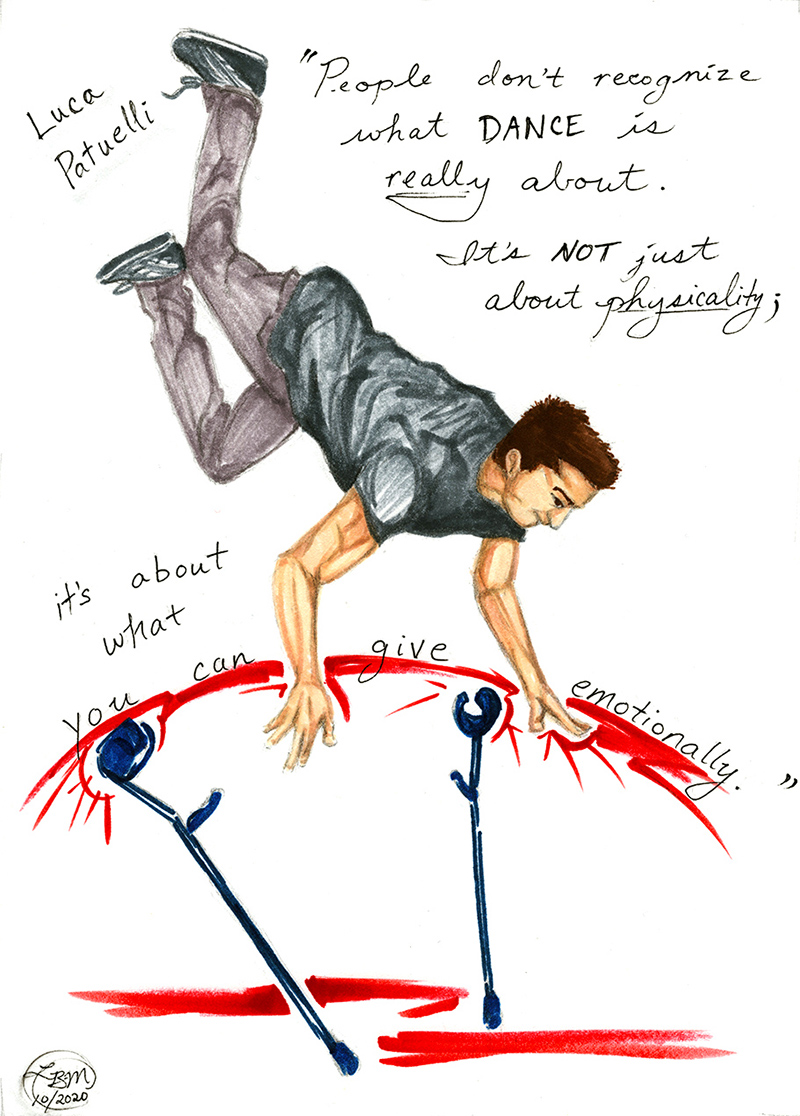

Luca Patuelli: “Dance Can Be Organically Inclusive”

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Luca “LazyLegz” Patuelli is a b-boy, choreographer, educator, and speaker based in Montreal, Canada. He is the creator and current manager of ILL-Abilities, an international breakdance crew comprised of seven dancers with different disabilities from around the world. Luca has garnered worldwide recognition for his unique dance style incorporating his crutches and arm strength. He also co-founded RAD Movement, Canada’s first inclusive urban dance program open to people of all ages and abilities.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

Image description: Luca is depicted diagonally upside down wearing a gray shirt and pants with his feet in the top left corner. His hands extend beneath him reaching for two blue crutches that are suspended upright. A red line of energy zigzags around his hands and crutches, and the quote, “People don’t recognize what dance is really about. It’s not just about physicality; it’s about what you can give emotionally” hovers around him.

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

I started dancing in high school where I saw breakdance for the first time. I grew up in Bethesda, Maryland. At lunch, there was a group of seniors cyphering, which is a circle where dancers enter one at a time. I had a lot of strength in my upper body because I use crutches to walk, so I was able to do pushups where I would lift my legs in the air and pump up and down. When the seniors saw that, they said, “Whoa, that’s awesome, you could be a b-boy.” They showed me what breaking was and I got hooked.

We started a club and practiced every day. Initially, I had trouble because of the footwork, so I created my own style based on my arm strength. I replicated the moves my friends were doing without the use of my legs.

I actually broke my leg at my first dance competition. I was rushed to the hospital for emergency surgery and was in a full body cast for two and a half months. I didn’t want to dance again. Once I got the cast off, my family moved to Montreal. I was in a new city where I didn’t know anyone, and I wanted to create that community around breaking that I had in Maryland, so I started dancing again.

It was about that time I realized I wanted to breakdance professionally. I started training hard. I joined a crew in Montreal and traveled around North America to compete in different competitions.

Through traveling, I met other breakdancers with disabilities. In 2004, I met Kujo, who is Deaf, and Tommy Guns, who is an amputee. I thought it would be awesome to create a super crew comprised of some of the best b-boys around the world who all have disabilities. In the breaking scene, it’s common to take the best members of various crews and fuse them together to create super crews for special events.

I started ILL-Abilities with Kujo, Tommy, and another guy, Checho from Chile, who released a video in 2006. Checho has a malformation where his feet come up to his knees. I wrote a comment on his video saying I’d love to cypher with him, and he responded immediately. When I told him about the super crew I was starting with Kujo and Tommy, he wanted to be a part.

In 2007, Red Bull had a qualifier for the Red Bull BC One, a big breaking competition. They knew about my new crew because I had been involved with Red Bull on other projects, and they wanted to bring ILL-Abilities to debut at the Red Bull BC One in Los Angeles. They didn’t have the budget to bring Checho, so they brought out myself, Kujo, and Tommy. It was the summer of 2007 when audiences saw ILL-Abilities for the first time.

A year later in 2008, I organized an event in Montreal called No Limits, and I flew out Checho, Tommy, and Kujo. That was the official debut of the full crew.

The rest has been history. Tommy is no longer part of ILL-Abilities, as he’s focusing on his own career. We were joined by Redo from Holland, Krops from South Korea, and Samuka and Perninha from Brazil. We’re seven dancers who represent six countries and, in the past 12 years, we’ve toured and performed in more than 25 countries. We developed a theatrical dance piece for festivals. We also do motivational entertainment at schools, conferences, and concerts.

Additionally, we lead breaking workshops for b-boys and b-girls looking to excel. We also teach integrated dance for people with disabilities. Finally, we have a training for dance teachers who don’t have disabilities on how to work with people with disabilities. We offer all this to make us more bookable.

Here in Montreal, I have several programs where I work with students with disabilities who are late-teen or adult with various intellectual and physical disabilities. My goal is to train them to have the tools to dance at a professional level.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

When I was competing more, I practiced two to three times a day. Since starting a family, my dance practice has become more gig oriented. I do a lot of motivational speaking at schools, and I try to give myself the challenge of not repeating material so, if I have a gig on Monday and Wednesday, I try to create a new set in between. As far as touring, in 2019, ILL-Abilities traveled to 13 countries.

I do a daily workout that’s about 30 minutes, but it’s throughout the day. For example, if I’m cooking and I have a free moment, I might do some squats or pushups. At least twice a week, I spend an hour uninterrupted in my home office dancing or working out. And whenever I’m stressed, I take deep breaths to realign myself. I’ve learned to meditate since 2017 when I experienced burnout. What helped me was refocusing on what’s in front of me and letting go of things outside my control.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

I once had a collaboration with some tap dancers. I showed up at the theater before they arrived and was told by the security guard that only dancers were allowed backstage. I insisted I was a dancer. Even when the other dancers showed up, the security guard thought I was injured. After the show, he apologized, but it wasn’t the first or last time something like that happened.

Although more people recognize me now, there are still those who don’t believe I’m a dancer. Sometimes I’ll show them a video of me online. People don’t recognize what dance is really about. It’s not just about physicality; it’s what you can give emotionally.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

There’s an assumption that there’s one type of disability, like, “He’s not in a wheelchair” or, “His legs are moving, so he’s not really disabled.” When I hear those comments, I think: Who are you to judge what disability is?

With ILL-Abilities, we never saw ourselves as disabled dancers. We didn’t think, “I want to battle the next disabled dancer.” We thought, “I want to battle the best because I want to be the best.” ILL-Abilities is a play on words. “Ill” means sick but, in hip hop, it means amazing or incredible, so ILL-Abilities is all about amazing or incredible abilities.

However, the media focuses a lot on our disabilities. We can use that to our advantage to promote ourselves and get gigs, and we can also use that platform to educate that dance can be organically inclusive. You don’t have to force disability into dance. One of the things I appreciate about hip hop is that it is inherently inclusive. Every day is Black History Month. Every day is Pride. In hip hop, everyone unites to celebrate the music, dance, and art. Obviously, there are egos and battles, but the genuine core is peace, love, unity, and having fun together.

For the media, I’d say focus on the dancer and the emotions they are expressing. Have the disability be mentioned in the second or third paragraph. In all honesty, it’s hard not to mention disability because it becomes the elephant in the room. But a dancer shouldn’t be celebrated just because they have a disability. The talent and effort must be behind them.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

In hip hop and breaking, most b-boys and b-girls are self-trained. They practice in the evenings at a community center or during lunch break at school. The beauty is that anyone can show up. If someone is struggling, a more experienced dancer might give them a tip, like, “Try placing your hand here,” or, “Lift your head a little higher.” In terms of disability, it allows people to just go and try whatever they can.

When I started teaching kids with disabilities, they had difficulty following me, so I started to teach concepts instead, like “This is what a top rock can look like, now show me how you might do it in a wheelchair.” My job as an educator is to help students develop their individual movement.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

It’s the same issue as with the Olympics and Paralympics. Some Paralympic athletes call themselves Olympians, while others think of Paralympics as something that needs to be differentiated. There’s the need for adapted spaces so that everyone can be accommodated, which is why the Paralympics is a separate event, but for the athletes with disabilities who think of themselves as Olympians, what they want is the same valor.

Assimilation is a difficult question in the sense that I don’t think there will ever be a right answer. ILL-Abilities has performed at major venues and festivals that weren’t about disability, but we’ve also been part of disability arts festivals. The positive thing about those festivals is it’s an opportunity to get to know each other and understand how our art forms are evolving. It’s more of a safe space, because you’re being seen by your peers, as opposed to outsiders who don’t know what you’ve gone through. I understand and support the disability arts festivals, but I also advocate for inclusion. If we want disability to be better understood, we have to put ourselves out there and be treated just like any other artist.

What is your preferred term for the field?

I don’t like “handicapped” or “invalid.” The origins of “handicapped” comes from beggars, “hand-and-cap,” and “invalid” means “not valid.” But the other terms I’m comfortable with. I’ve been using “differently-abled,” but I heard recently that it’s no longer accepted. Five years ago, I was using “special needs.” I’m not going to lie; I have difficulty keeping up to date with terminology. I start all my workshops by saying that, while I use the terms “differently-abled” and “integrated dance,” if anyone takes offense, please educate me and recognize that terminology evolves. On top of that, every country uses different terminology. I was in Singapore and Hong Kong in 2019, and they were still using “special needs.”

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

Europe, the UK, the US, and Canada are making progress by supporting disability in dance through grants, performance opportunities, residencies, and making theater spaces accessible. One of our biggest challenges is when theaters say they are accessible but only have accessible seating; getting onstage is not accessible. People are becoming more aware of that.

Any other thoughts?

I recognize I wouldn’t be who I am today without my disability. In that respect, thinking about integration or assimilation is thought-provoking. I understand those who don’t want to join the mainstream, but I do. Like any other art that has an underground and mainstream component, we shouldn’t criticize the dancers who want to stay in a particular community or the dancers who want to go outside it. Either way, we should be ambassadors for dancers with disabilities. We should be educating and encouraging each other.

Pictured: Luca Patuelli, Photo by Brian Kuhlmann

Image description: Luca is pictured in mid-movement. His left crutch is on the ground and his body swings above it so his legs and his other arm and crutch are suspended and pointing front. He is wearing jeans and a red shirt. A pier and blue sky are in the background.

~~

To learn more about ILL-Abilities, visit www.illabilities.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!