Erik Ferguson: “Dancing is How the Body Learns”

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Erik Ferguson is an anti-virtuoso movement artist in Portland, Oregon, and co-founder of Wobbly Dance. He studied improvisation with Alito Alessi in Trier, Germany in 2003 and has performed and taught DanceAbility and contact improvisation throughout the Pacific Northwest, as well as in the United Kingdom, Oaxaca, and British Columbia. He also studied improvisation with Deborah Hay and Barbara Dilley. He is a student of butoh and has studied with Akira Kasai, Koichi and Hiroko Tamano, Mizu Desierto, and others. His performances explore themes of embodiment, gender identity, and extremes of human emotion.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

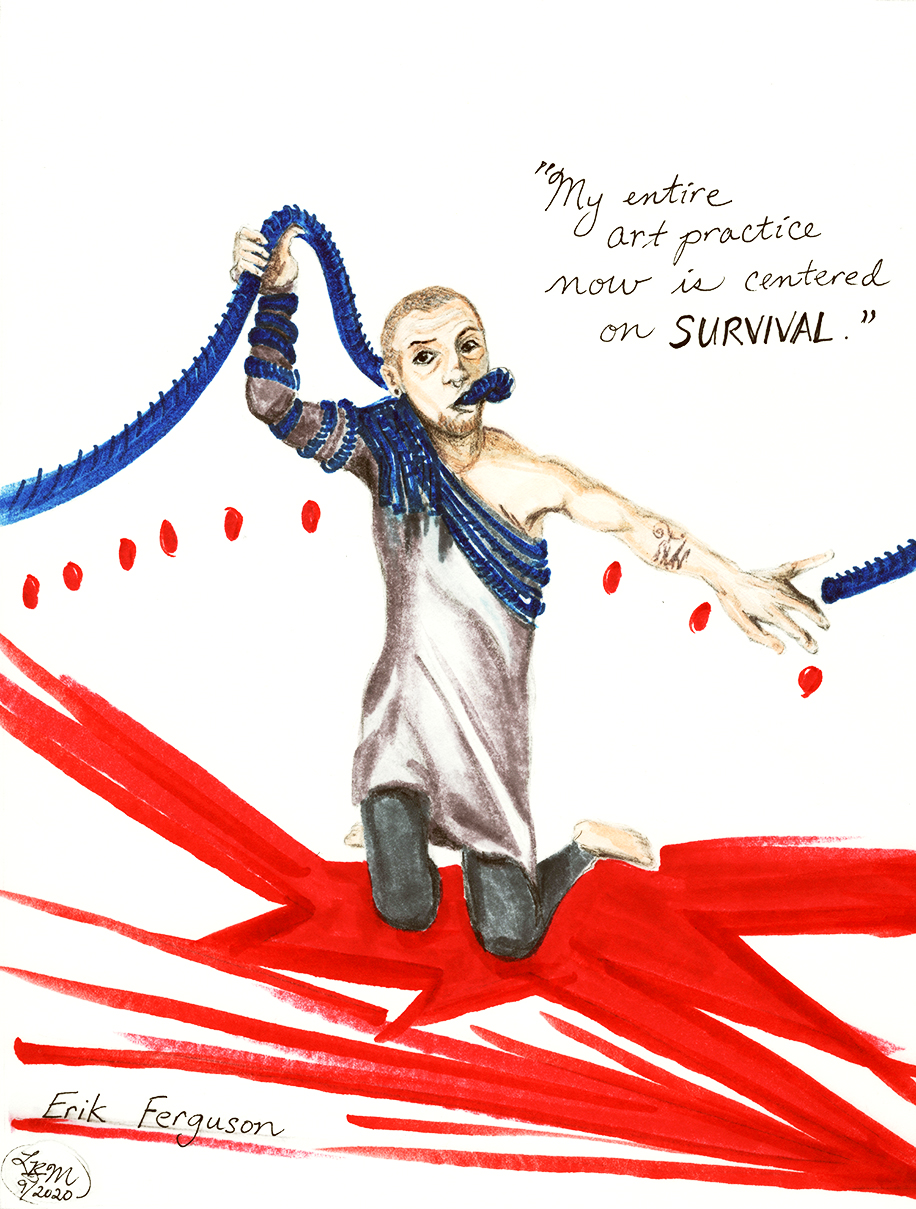

Image description: Erik is depicted facing front and kneeling on bold red lines of energy. A blue breathing tube extends from his mouth and artfully wraps around his chest and right arm before extending out of the frame. He is wearing gray. The quote, “My entire art practice now is centered on survival” floats above his left shoulder.

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

I got my start in dance in 2003 when I met Alito Alessi. He was doing a DanceAbility workshop, which is based on improvisation, where I was going to college. I almost didn’t go but went on a whim. I felt very shy; I was a wallflower and never danced, not even at family weddings, but there was a moment when my body made a choice. I was really surprised. I became fascinated by improvisation and started doing solos in my living room. Alito invited me to do the teacher training the same year in Trier, Germany, in 2003.

After that, I learned about contact improvisation and started going to jams. I met key figures in the fringe dance scene. I ran into Karen Nelson at a jam, and she made it possible for me to go to the Seattle Festival of Dance Improvisation. There I met Yulia, who would become my wife. We later did an AXIS Dance Company training together. Once the ball got rolling, it didn’t stop for quite a while.

I found out about butoh from photographs. I noticed that some of the postures looked like the postures my body takes with the condition I have. It piqued my interest. Obviously, something like ballet wasn’t inspiring to me for any number of reasons. When I saw stereotypical butoh postures, it looked to me like the gait of people with cerebral palsy.

The first butoh workshop I went to was with Eiko and Koma. They came to Portland as part of the Time-Based Art Festival and did a workshop at a performance space in a historic building. I literally left my wheelchair and climbed steps to join the workshop but, once I arrived, I found the material accessible. I didn’t have to do a lot of adaptation; it felt natural.

About 12 years ago, Yulia and I started collaborating with Mizu Desierto, who runs a project called Water in the Desert. She focuses on Japanese contemporary dance and organizes a program called Butoh College, which brings in international teachers each year. We were studying with her and she invited us to do a piece. It started a long partnership which has included many performances.

Yulia and I didn’t operate in disability dance environments for a long time. We were operating in the improv or alternative dance scene. Eventually, we decided to form a company with just the two of us, called Wobbly.

It took me a long time to come to disability culture. I’m one of the three founders of the Disability Art and Culture Project in Portland but, for a long time, I didn’t want to be associated with disability. I eventually became friends with well-known people in the disability field, one of whom is Petra Kuppers. She told me that she was triggered when I talked about disability culture as a place of lack. There’s the stereotype that it’s provincial but it’s actually a huge world of professional work. I came around about 10 years ago.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

Wobbly has been hibernating for a while. My entire art practice now is centered on survival. When you have a disability to the extent that my wife and I do, daily needs are fought for. It gets harder to make art in a traditional sense, but I feel like we’re living in an artistic way in terms of our surroundings, the people we associate with, and what we talk about.

Even though I’m in my 40s, I feel like I’m having the experience some dancers have in their 60s or 70s. I was capable of lots of movements; I could do contact improv lifts, rolls, and balances, and get in and out of my chair and across the floor. Over the past five years or so, I’ve become more immobile. I get up in the morning and call myself a dancer, but sometimes I say I used to be a dancer. It’s a hard question for me to answer.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

Here’s one of my favorite stories about this: In 2004, I travelled to teach DanceAbility with a friend in Oaxaca at a rehabilitation center in a town of 1,400. We figured out how to travel cheaply by flying into Mexico City and then sitting on a bus for 26 hours. We were coming back to Mexico City after being on the bus and were going through customs. I would have told the customs officer, “We’re coming back from vacation,” or “We were visiting a friend.” But my friend said that we were coming back from teaching dance classes. The customs guy laughed this super hardy laugh at the idea of a blind guy and a guy in a wheelchair teaching dance. But that’s the reaction people have, especially if you’re not a big-built paraplegic in a sporty wheelchair.

That happens even now. Yulia and I did a choreography project last summer with people who have developmental and intellectual disabilities. While we were doing some blocking onstage, this woman in the choir ran to the director and told him she was worried the wheelchairs wouldn’t fit in with the rest of the dancers. The director turned around, cocked his eyebrow at us, and responded, “Well, they are the choreographers.” I constantly have to prove myself. The idea that I might dance in a body like this is really hard for people.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

Yulia and I did a butoh piece in a group show with Alice Sheppard in Chicago a few years back. The review of the show said the performers were delightful except us, which described our piece along the lines of “less than delightful and scared all the children.” The other performers were doing uplifting and athletic stuff with their wheelchairs and crutches. In contrast, we did a durational creepy performance that wasn’t digestible as appropriate disability expression in that context.

The other struggle is that reviewers want to know what our disabilities are. Yulia and I usually respond, “We never answer that question on the first date.” They want to center the diagnosis, and I want to know what they want to do with that medical information.

Instead, look at the art. Ask how it makes you feel. What are the colors? What is the speed? What is the lighting? Did you feel annoyed? It’s okay to feel annoyed. Just because there’s a wheelchair doesn’t mean you have to like everything. Just look at the art for what it is. Don’t be afraid to laugh or cry. And if someone gets offended, too bad.

My friend, Rhona Coughlin, is a dancer in Ireland, and she doesn’t get offended easily. She heard someone wanted their money back after a performance she gave, and she went to talk to the person. They told her they didn’t pay to watch a disabled person drag themself around on the floor. I might have been upset by that, but she told them, “Look, you came out, you tried it, you paid your money, you didn’t like it, too bad, go home.”

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

There absolutely are not enough training opportunities for people with disabilities and there need to be more. Yulia was able to go to college for dance, which I find phenomenal. It was made possible by one faculty member making the curriculum work for her. Without that one individual working as an advocate and advisor, she would have been pushed out. Anyone who wants to study dance at the college level needs to be able to. If someone is sitting in the corner wiggling their pinky, dance faculty need to figure out how to grade it. Dancing is how the body learns, and people with disabilities need more places to do that.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

I think it totally depends on the person and their individual aspirations, abilities, and disabilities. There are certainly people out there with disabilities who potentially could go to an elite ballet school, and then there’s me who’s not particularly interested. In the mainstream, dance is considered an exceptional and exquisite way of training the body. There are certainly people with disabilities who can take part in that. And then there’s this whole fringe side, like standing in a room, breathing, and moving tiny. There has to be more of all of it.

There’s a quote by Tatsumi Hijikata [one of the founders of butoh] that says, “Only when, despite having a normal, healthy body, you come to wish that you were disabled or had been born disabled, do you take your first step in butoh.” He was fascinated with the movement of people with disabilities. Whether that’s tokenization, I don’t know. When I took a workshop with Akira Kasai, I asked him if I was the first person with a disability to come to his class, and he said, “Oh no,” like I wasn’t that special.

What is your preferred term for the field?

I fluctuate between a few terms. “Mixed abilities dance” can be confusing because it’s not clear if it’s dance for all ages or experience levels. “Mixed with what?” is one of the criticisms of the term. I don’t hear “adaptive” dance as much, but I don’t like it because it sounds like occupational therapy. “Inclusive dance” has the same problems as “mixed abilities”; who is being included? The term “physically integrated dance” I first heard around AXIS, but one of the things I struggled with when I studied there was their discomfort around working with people with intellectual disabilities. I’m curious what they would say today, as this was years ago.

Accessibility that includes cognitive and developmental disability is the last frontier of the disability justice movement. The last piece Yulia and I choreographed was solely on people with intellectual disabilities. It was an original rock opera through an organization called PHAME. They hired us to set choreography on 10 people with developmental disabilities. The experience made me realize how in my head I am about improv. This is not to say there should or shouldn’t be complexity of thought, but I learned a lot about how to teach improv to people who don’t process information the same way I do.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

Little by little, you can see changes. Rodney Bell performed on So You Think You Can Dance in 2011. Things like that come up more often where you can see people with disabilities in mainstream settings. But it’s just one type of polished mainstream dance. As for me, I don’t do mainstream dance, so part of me doesn’t care.

Pictured: Erik Ferguson, Photo by Ward Shortridge

Image description: In this black and white photograph, Erik is pictured from the waist up wearing a dark tank top. His breathing tube extends from his mouth, twists around his neck, and then continues twisting around his right arm. His left arm is raised to the side.

~~

To learn more about Wobbly Dance, visit www.wobblydance.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!