Alexandria Wailes: “Let Us Move!”

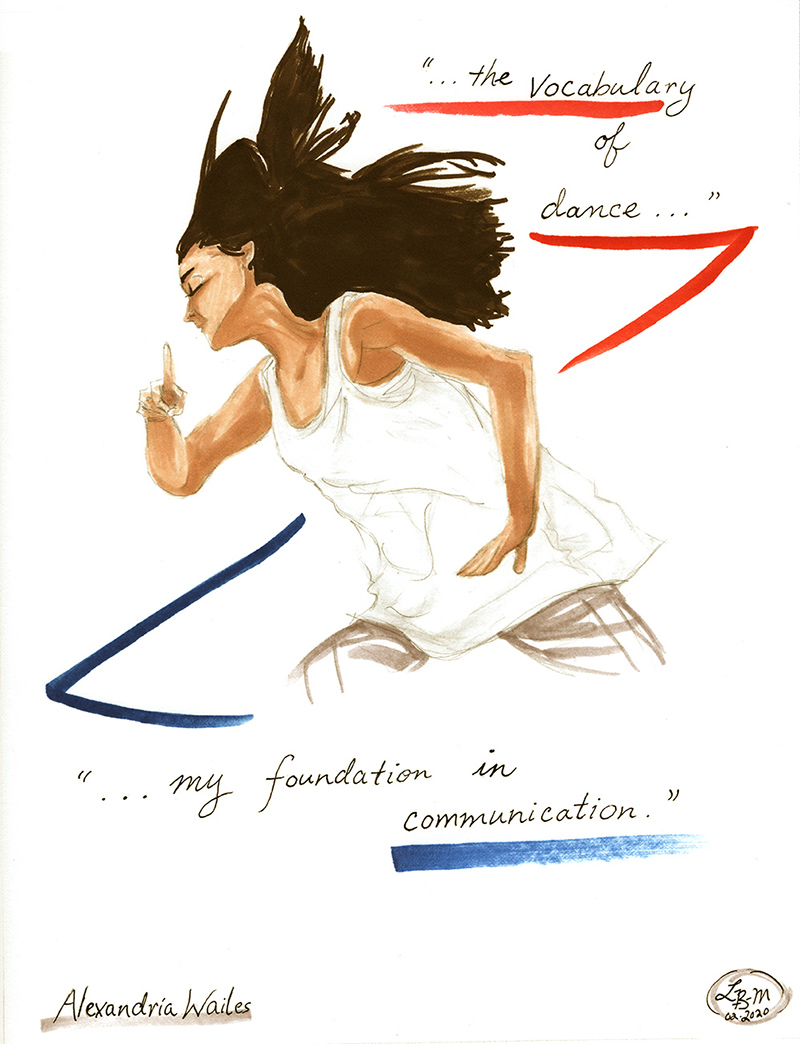

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Alexandria Wailes has worked as an actor, director, choreographer, and American Sign Language (ASL) consultant in television, film, music videos, web series, Broadway, and Off Broadway. She toured with the Deaf West Broadway production of Big River, served as the associate choreographer for the Tony-nominated Deaf West production of Spring Awakening, was a member of the Heidi Latsky Dance Company, worked as a museum educator for the Whitney Museum of American Art, and was a teaching artist with Theatre Development Fund and Interactive Drama for Education and Awareness in the Schools Inc.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

Image description: Alexandria is depicted from the top of her legs up in mid movement as if she is turning toward the right. Her arms are bent at the elbows. Her right finger is pointed in front of her and her left hand is flat to her side. Her hair flows behind and above her head. She is wearing a white tank top and white pants. Red and blue lines of energy zigzag around her along with the quotes “…the vocabulary of dance…” and “…my foundation in communication.”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

My first exposure to dance was when I was two or three years old. After I contracted and recovered from meningitis at 13 months old, doctors gave my parents several suggestions. One doctor suggested I be placed in dance classes. He said, “It will be good for her balance and physical coordination.” All around the same time, I learned dance, sign language, and obtained speech and auditory hearing training for what I had to work with. I think of the vocabulary of dance as my foundation in communication. My parents told me that once I was introduced to dance classes, that was it, I was taken with it.

For much of my childhood and early teen years, with a few gap years, I went to dance classes on weekends and after school. As a teenager, I decided to reimmerse myself. I had become more conscientious of how I sounded when I was speaking. When I got back into dance, it was very cathartic and freeing. However, I didn’t have the classical ballet body even though I was classically trained. It was an ongoing journey of trying to understand where I fit.

For college, I attended The University of the Arts in Philadelphia, where I was the only Deaf person in the dance department. It was definitely a very interesting and fantastic experience, yet a challenging journey because there was a real culture shock in communication the first year. Let’s back up a bit. While I was in my second year of high school, one of my teachers at Delaware School for the Deaf informed me and my parents about this summer intensive performing arts program at Gallaudet University. It was called the Young Scholars Program and it brought in high schoolers from all over the country. The month-long intensive had a faculty that was predominantly Deaf; this is where I met my first ever professional Deaf dance instructors. I ended up transferring over to the Model Secondary School for the Deaf (MSSD), which is on Gallaudet’s campus, for the last two years of high school. Returning to a predominantly hearing environment for college was challenging, as ASL was not the common language used among my peers and teachers.

During those years, there were many highlights. Thanks to the strong performing arts program at MSSD, I performed in Senegal. During and after college, I performed with a group from Washington DC in Japan, India, and Romania.

I got into choreography after college. It’s difficult auditioning and going to dance classes when you don’t have money and are barely paying the rent, even with roommates. That’s when I started venturing into acting, directing, and choreographing. In 2002, I choreographed for and performed with a collective of dancers in Washington DC called Pentimento for Deaf Way II International Arts Festival. It was called Pentimento based on the idea of an oil painting, how new layers can be added and then stripped off to reveal the backstory of the canvas. It was a short-lived company as the members were from around the country and world.

Over the course of 20 years, my work as a teaching artist, choreographer, actor, dancer, and director has enriched my journey as an artist. I taught workshops on contemporary dance and hip hop with high school students. I worked with the Heidi Latsky Dance company for a few years and ended up performing at American Dance Festival in my late 30s, which goes to show it is never too late! I worked as the associate choreographer on the Deaf West production Broadway revival of Spring Awakening. My latest collaboration as a choreographer was with Spellbound Theatre which focuses on immersive theater for babies, toddlers, and their guardians.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

Full disclosure: I’m not dancing as much as I used to. I haven’t been able to afford taking dance classes, and much of my schedule has been focused on artistic sign language consulting and directing for the stage, TV, and film. Unfortunately, that means a lot of time sitting on the creative’s side of the table working with my colleagues and with the actors. Despite not actively dancing as much, my inherent sensibility of movement has informed many of my choices made in productions that incorporate ASL. A lot of the work I do with the actors is watching and supporting them in how to be, move, and use space while signing.

I work as the director of artistic sign language. The job used to be called an ASL consultant or a sign master. It’s a combination of choreography and dialect coaching. It’s often confused with interpreting, which it is not. An interpreter facilitates communication between a non-ASL user and an ASL user. A director of artistic sign language is completely focused on the authenticity of the storytelling, the sign choices made by the director, actors, and other members of the creative team, basically how language lives in and on the body. For example, if you have one Deaf character in a piece and everyone else is hearing, how do they interact? I explore those possibilities. Because sign language is very physical and spatial, my work in artistic sign language is informed by my dance history.

Back to my dance practice, I’m about to enter a new phase. I am currently an actor/dancer in The Public Theater’s For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf. It’s nice to be dancing a lot and telling stories through movement, gestures and ASL.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

“Really?” That’s one. If they are hearing, they always say “How can you hear the music?” If they’re Deaf, they say, “You can’t be a dancer.” It’s just part of our history, this idea that music lives in the senses of the hearing. However, that’s not true; music and sound function on all levels through the vibrations. Musicality and rhythm are in our bodies. But if a people think dance is tied to music and music is something you hear, then it doesn’t compute that I’m a dancer.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

The common phrase that comes up is one of inspiration or pity, like, “How are you doing that?” said with surprise. It comes across as sympathetic, but when you’re on the receiving end, it feels icky. When you get that more often than not, you start to question what you are doing to begin with. That kind of reaction isn’t about how I’ve manipulated or expanded the vocabulary of dance. It’s more like, “Oh wow, good for you, you’re so beautiful.” It’s very stereotypical, instead of letting my work challenge people or engage in critical thinking and conversations about how dance lives within the body.

I’ve always believed that dance is equal parts musicality, technique, and soul. How can you communicate the soul and bring it forth into space? A lot of Western classically trained dance is strongly focused on technique. For dancers with disabilities, the bar is Western dance technique. That’s the expectation we must hit. So, when we dance, the reaction is often, “Ah, wow, good for you, that’s amazing, so beautiful.” I read it as ingenuine. They just see the physicality of the body and are not thinking about how the person dancing is expressing themselves. We’re just inspiration for them. I think that’s our biggest barrier. But we don’t have time for this inspiration narrative anymore. Let us move! We have a lot to clear so we can do our thing.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

There’s a huge lack of easily accessible studios. I’m talking on an architectural level. Some dance studios are walkup, or there’s one elevator that people in wheelchairs can ride with the trash. It’s ridiculous. Of course, in an older city like New York City, things cost a lot of money to renovate, but we need to find creative solutions.

I also think dancers with disabilities need more exposure to different types of dance across the board. We need more dance teachers who are working with low vision dancers, or people in wheelchairs, or those with a missing limb. Dance is often segregated.

Dance is how you live and move in your body. How you move in space, that to me is dance. I want to challenge perceptions of how bodies can move in space.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

Yes and no. If you have different bodies in space, that’s fantastic; the experience of interactions, exposure, experimentation, and play helps people to better understand each other just by the diversity in the room. But some spaces are better suited for common ground and expressing communication. When I dance with a company of all-hearing people, for example, there’s always going to be the process of deciding to bring in an interpreter. Communication is faster with an all-Deaf company, and there’s none of that “What can you hear?” or “Let’s use sign language as part of the choreography because it’s so beautiful” sentiment. This is my language! There’s definitely merit in having spaces where we can come together, feel safe, and create. That’s equally important. Most able-bodied hearing dance companies have never worked with a Deaf person. But we’re always the minority accommodating the majority, instead of everyone working together.

What is your preferred term for the field?

Speaking for myself, not for my community, it depends on who I’m interacting with. I give myself permission to say, “I’m a Deaf dancer,” or, “I’m a dancer who happens to be Deaf.” I use those interchangeably.

A company might say it has a range of dancers with different abilities but, to me, that description sounds like a hot soundbite. I just want it to be a dance company, nothing attached to it. A descriptor like that might be in the company’s mission, but I like to stay away from the pity or the inspiration porn complex. I want to avoid that language.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

Slowly but surely. There’s definitely more awareness out there and more visibility and opportunities. As far as shifting society’s frame, one person can’t do all that work; it takes a vast community with everyone being a part.

Any other thoughts?

It’s important for dance companies to have in their line budget funding to allow for dancers with disabilities to be a part of the conversation. Have an interpreter in the audience or auditory descriptions for people with low or no vision. Rent spaces that are accessible. It goes back to education.

Pictured: Alexandria Wailes, photo by Darial Sneed

Image description: Alexandria is pictured onstage sitting on her knees wearing all white with her hair down around her shoulders. Her eyes are closed and her arms are extended in front of her bent at the elbow with her hands raised. Her fingers are open wide.

~~

To learn more about Alexandria’s work, visit www.alexandriawailes.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!