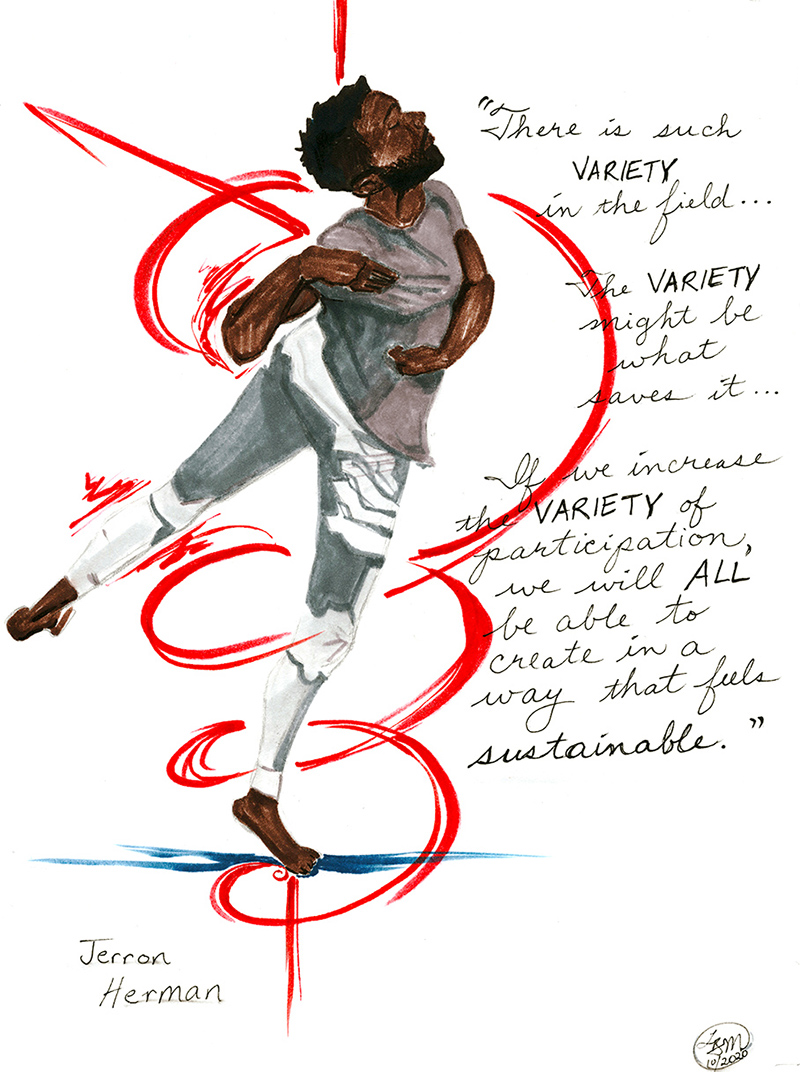

Jerron Herman: “A Political Understanding of Disability”

BY SILVA LAUKKANEN; EDITED BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Jerron Herman is a New York City-based interdisciplinary artist who employs dance, text, and visual storytelling. Originally from the Bay Area, he moved to New York City in 2009 to study Dramatic Writing at the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU. He then studied Media, Culture, and the Arts at The King’s College, where he graduated in 2013. While in school, he began performing with Heidi Latsky Dance and quickly became a key member of the company. Jerron has performed at venues like Lincoln Center and The Whitney Museum of Art, and most recently is pursuing his own choreography.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

Image description: Jerron is depicted balanced on his left leg with his right leg extended behind him. He is facing to the right of the frame, his left arm in front of his stomach and his right arm angled into his side. He is wearing gray and white pants and shirt, and red lines of energy swirl around him with the quotes, “There is such diversity in the field…The variety might be what saves it…If we increase the variety of participation, we will all be able to create in a way that feels sustainable.”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

Seán Curran, chair of the dance department at NYU, is who brought me into dance. I was an educational apprentice at New Victory Theater in the summer of 2011, huffing the pavement trying to be a theater administrator and writer. That’s why I came to New York. Seán was working at the theater then. On my first day, he said, “I don’t need an assistant. Why don’t you just participate?” He was leading an intensive for public school teachers on how to integrate dance into their curriculum. It was the first time I was exposed to dance history and education. I guess Seán took a liking to me, because he encouraged me to make a solo that I showed for the final day of the workshop, which was also the last day of my internship.

All this time, Seán was telling me about a company in the city that created work with people with disabilities, Heidi Latsky Dance. One day, he literally handed me a ringing phone and it was Heidi’s manager. I ended up in a studio the next week auditioning for Heidi. She said, “Show me what you got.” It was a lot of improv over a two-hour session. At the end, she asked me my school schedule. Literally overnight, I became a professional dancer rehearsing with the company three to five times a week.

No one at school knew I was in a dance company. I didn’t know how to tell people; it was just so different. I went to Boston for a gig on a Friday night, and my roommate and bestie started texting me, “Where are you? I haven’t seen you in like 48 hours,” and I was like, “I forgot to tell you, I’m performing in Boston right now, I’m a professional dancer.”

One of my favorite memories was when we performed GIMP at Lincoln Center Out of Doors in 2012. I stepped in to replace Lawrence Carter-Long for his role in GIMP, and it was wild for me to be a replacement for a part that was specifically made for a person with cerebral palsy. At the time, I was the youngest member of the company. I really looked up to the other dancers, who were radical disability activists. And then the non-disabled cast members knew so much about the dance world. I was getting a mashup of disability history and dance education all at once, wrapped up in hardcore activism power.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

I’m interested in re-envisioning past events from my personal experience. The idea of memoir is so pervasive across disciplines, especially with respect to disability. I’m interested in abstracting and interrogating moments in my personal narrative, and then making them less personal so that people can insert themselves into them.

My most recent piece, Phys, Ed, is a solo that draws from my experience in PE as an adolescent, and then extracts and explodes it to transform the way we look at PE. That’s my hope at least. The movement is focused on specific elements of the body, like balances, jumps, or pushups in gym class. I execute the movements differently because of my disability.

I had a residency in Staten Island for a month where I had studio time to just play and create. For a couple sessions, I explored how I could balance or use my gait in expressive ways. I went in cold one day and just worked out my trochanter and glute, and that became the choreography. There was this unintended effect of therapy or warming my body. I just moved how I move. In company settings, I interpret other people’s choreography. This was a way for me to try out how I would move if I was the one asking.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

Interest. Raised eyebrows. I think this is mostly because people don’t see dance as a viable occupation. The first reaction is often, “You can support yourself?” It is always an economic question.

I know why people aren’t as dubious with me as they would be with someone in a wheelchair or someone who is blind. I “present” as less disabled than others. That’s definitely problematic. But the economic question irks me because people still don’t give art its due. Being a professional is a novelty and considered kind of cute. People don’t think, “Of course you work fulltime, of course you work as many hours as I do at my tech job.” Art is placed on a lower social rung.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

There’s no literacy. People are like: “I don’t know what physically integrated or disability artistry means, so I am not going to learn. I don’t know what it is, so I’m not going to engage.” That reaction is in tandem with blatant ignorance and fear.

In a review of GIMP at Lincoln Center, the writer wrote that I gave the middle finger. At the time, my hand would spasm and break out in the middle finger. He thought it was my internal aggression toward able bodied people. Dude, I just had a spasm, and it manifested that way! Though I found it to be funny, the guy assumed he knew more about my disability than he did, and that was upsetting.

With regards to presenters and promoters, it’s like there’s this quota in the presenting schedule where there is only one slot for disability artists. It’s this attitude of: “We presented AXIS Dance Company last year, so we don’t need to present Heidi Latsky Dance this year.” I am also curious about awards with respect to project grants that only pick one disability arts organization at a time. There is such variety in the field, and such variety is needed. I don’t want the field reduced to a monolith. It would be such a shame if only one company or artist continues to get visibility, because different artists with disabilities offer different things. Pioneer Winter can satisfy something different than Alice Sheppard can. There is a need for many disabled dance artists to receive funding and opportunities, even within the same state or on the same side of the country.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

Companies like AXIS have 30 years in terms of a foothold, so they get a lot of attention and they have their audience base. But the field is not creating new artists at the same rate as the non-disabled community. Artists from non-disabled dance companies become their own entities at a quick pace, but I don’t see many individual artists coming out of companies like Full Radius, AXIS, or Heidi Latsky Dance and becoming their own entities. There is a real bottleneck in terms of what is possible. There aren’t offshoots of collectives happening every year. There is just less on top of less.

Organizational support is key. It creates credibility in a real way. If we are asked to be on a panel, sit on a committee, or be on a board, it elevates that space, and it also elevates our voices. The networking that comes from that is crucial to change. Creating opportunities not only starts from leadership but also from dynamic participation. The solution is to take ground outside of the studio: to take ground in conferences, in educational settings, and in boardrooms at the same time as we are making work. We need more voices on the backend to inform what is being said and seen on the frontend. And there are more qualified people than I ever would have guessed; I am constantly being introduced to awesome artists who are ready to be in those rooms today.

The under 30 crowd is ready and available. I have a sense that the phenomenon of living under the ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act] has made younger people with disabilities more aware and qualified to disrupt places of power because we have been more integrated into society than previous generations. I never was placed in a special class, so I never thought my rights were separate. That helped my confidence; I’ve always thought I should be included.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

I fear disability in dance will go the way of every other category of dance. It will fight for the same kinds of toxic prestige and prominence as ballet, for example. It will become as exclusive as other forms. We will want the same awards and accolades. That is my only fear for disability in dance. I hope that, intrinsic to its nature, it can show other dance forms how different dance can be.

I am interested in how disability in dance doesn’t go the way of codification. The variety of the field might be what saves it. I don’t want disability in dance to become a monolith with a certain way of doing things that sells the tickets and gets the money.

What are your preferred terms for the field?

I love “physically integrated” to talk about people with and without disabilities onstage together. It can also refer to the different ways that dancers with different disabilities, like an ambulatory dancer and a wheelchair dancer, might collaborate. Unfortunately, “physically integrated” is only talking about the physical expression of disability, not invisible, intellectual, or developmental disabilities.

I do not like “mixed abilities” because for me it doesn’t refer to the body, it refers to mixing disciplines. I don’t know about “inclusive” either. I think it’s a buzzword that needs to be qualified because it is also used to refer to race and gender. There isn’t a context of “inclusive” which just refers to disability, so it’s unspecific.

I like “disability arts” as a framework because I recognize that the content, research, performance, and production elements all come from a political understanding of disability. When I hear “disability arts,” I know it’s going to be created for an audience who is disabled. “Disability arts” is disability specific.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

I said earlier that I fear the field will become a monolith. Our organizing needs to be deeper than just getting jobs in the dance world. We need to look at how disabled artists are working in other fields like theater, visual arts, and poetry. They have different perceptions on how to integrate aspects of accessibility that can be approached in dance as well. I love when disability arts are cross disciplinary and encompass a political identification so that our practices are under the same umbrella and we find solidarity. I feel optimistic and energized by that way of working together. If we increase the variety of participation, we will all be able to create in a way that feels sustainable.

Jerron Herman, Photo by Daniel Kim

Image description: Jerron is pictured from the torso up. He is slightly leaning forward and looking off to the right of the frame with intensity. His left arm twists in front of his stomach, and his right arm arcs above and behind him. He is wearing a gray tank top and is pictured against slated wood.

~~

To learn more about Jerron’s work, visit jerronherman.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!