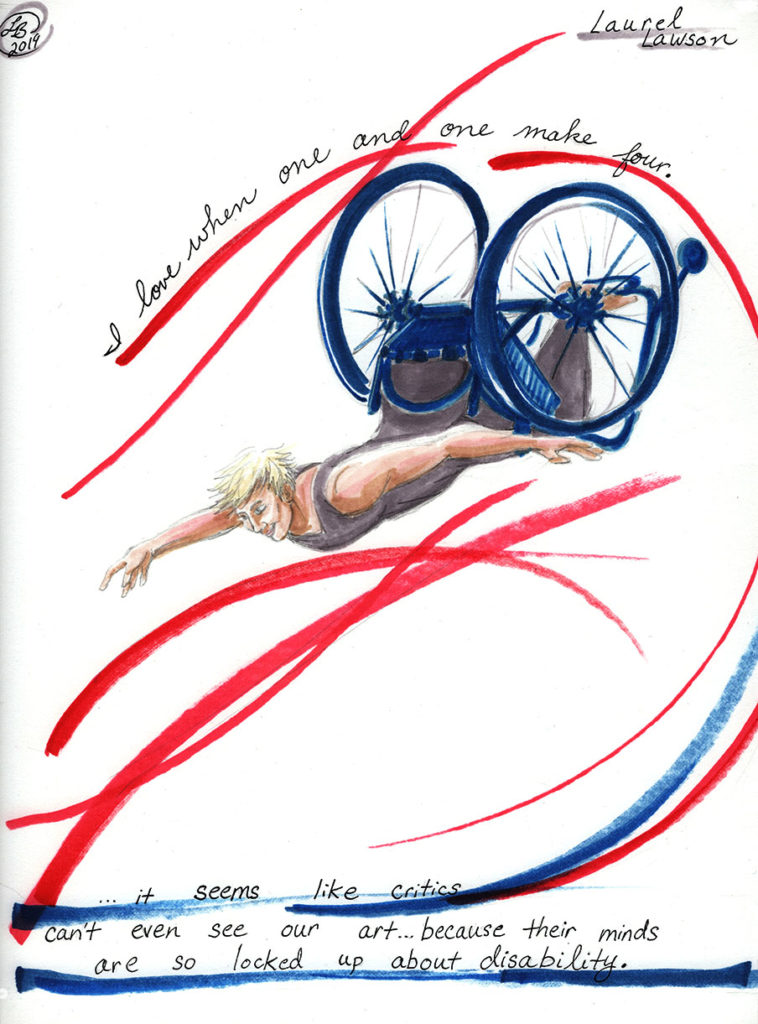

Laurel Lawson: “We’re Fighting for Artistic Acceptance”

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Laurel Lawson joined Full Radius Dance in 2004 and has since performed extensively with the company as well as with other collaborations and solo projects, like Alice Sheppard’s Kinetic Light. Career highlights include tours and a film appearance in HBO’s Warm Springs in 2005. In addition to performing, choreographing, and teaching dance, Laurel is also an advocate, public speaker, para-ice hockey athlete, and the product designer and co-founder of an engineering consultancy based in Decatur, Georgia. Laurel was a 2019-2020 Dance/USA Artist Fellow.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

Image description: Laurel is depicted upside down with her wheelchair at the top of the illustration and her body hanging down from it with her back arched away from the ground and arms reaching out to the sides. Red streaks of energy swirl around her along with the quotes, “I love when one and one make four,” and, “… it seems like critics can’t even see our art…because their minds are so locked up about disability.”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

I came to dance almost by accident. My plan was to pursue an MD-PhD but, after running a lab as an undergrad, I burned out and took a gap year working as an actor and musician. I grew up in music and theater; I was onstage with a touring gospel band when I was four. One of my high school goals had been to go to a conservatory and double major in music and science. Unfortunately, my wrists did not agree; at one point I was practicing piano about six hours a day and blew out both wrists. Although I had to give up piano, it didn’t sour me on music. I continued working on the side as a gigging musician through college.

A year after college, Douglas Scott, director of Full Radius Dance, taught a class at Shepherd Center, the premier Southeast rehab facility. It’s a pretty big center for wheelchair users in Atlanta, and they host most of the sports teams, so I was in and out playing basketball and doing peer counseling. I figured, why not check out the dance class?

I was terrible. It was the first time I’d ever been exposed to modern dance. I’m not even sure I had seen a modern dance concert before. It was fun though, and interesting to be challenged as a complete beginner. A couple months later, Douglas sent me an email and asked me to audition for the company. I had no clue what I was getting into.

I was the only person auditioning that day. I took class with the company and then watched rehearsal. I still felt like I sucked, but I was asked to join the company. I thought, “Sure, I don’t have anything going on in the mornings right now.” Two months later, I was in my first performance in Kentucky. It was pretty overwhelming.

I’d been dancing just over two years when we did a national tour with Dancing Wheels and AXIS Dance Company. Evidently, dancing stuck. The first couple years are a bit of a blur; coming in as an adult and learning to be a professional dancer is a unique experience. I came to dance with a lifetime of athletic training and theatrical experience. Still, dance is completely different.

It’s easy to remember tours as highlights. Italy was a big experience, but I’d also include among the highlights the experience working collaboratively in the company, like the first time a phrase I created made it into a final piece. There’s also the first time I was recruited to work with a choreographer outside the company who didn’t normally work in integrated dance. Finally, putting the piece DESCENT together with Alice Sheppard was a highlight.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

Like most dancers, it varies depending on the day. Right now, being in two companies (Kinetic Light with Alice Sheppard and Full Radius Dance) is really challenging. I dance six days a week. When Alice and I are touring or in a residency, we are basically doing 12 to 18-hour days, either in the studio or in active preparation or recovery. When I’m in Atlanta with Full Radius Dance, I might dance anywhere from three to five hours a day. I take class outside the company while on tour, as a lot of my favorite teachers are in New York or the Bay Area.

I also play para-ice hockey. If anything, I think dance informs hockey more than hockey informs dance. A hockey sled basically involves balancing on the blades of ice skates, but on your butt. It takes immense core strength. I lift weights regularly as well.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

When I started dancing, and for the better part of a decade, there was often either puzzlement or polite disbelief. I don’t mind people being puzzled or confused; if they’ve never seen a disabled dancer, that’s a legitimate reaction. I rarely get polite disbelief anymore. With people who are arts literate, there’s a chance they may have seen some physically integrated dance. And now I can just show photos on my phone; “Show, don’t tell,” makes the conversation easier.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

The primary issue is that critics project their own narrative of disability onto what we do. Frequently, it seems like critics can’t even see our art or technique because their minds are so locked up about disability. That’s certainly not true of every writer. Some have done a good job educating themselves enough to write about what we’re doing technically and artistically. It’s about actually critiquing the work, instead of, “There are people in wheelchairs, and they don’t move like I expected them to move.” We want and need critics to think and write about our work, but it must move beyond the 101 level.

One review here in Atlanta particularly annoyed me because it referred to the disabled dancers as “performers” and the nondisabled dancers as “dancers.” It was meant to be a good review, but the language choices made it clear what the critic implicitly thought. Every critic has biases, but, in an ideal world, I see the job of the critic as coming from a clear place without projections or stating biases as artistic arbitration.

I find it extremely rare that people want to offend. Just knowing the terminology is helpful and understanding why “wheelchair bound” and “handicapped” are inappropriate and harmful. The “overcoming” and “inspirational” narrative is also something we’re tired of. Dancers would like to be covered equitably. We’ve had instances where the dancers with disabilities are covered in depth to the exclusion of the nondisabled dancers, and that’s not equitable either.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

Of course not. There are several key points in the training conversation. Not only is it difficult to learn as an adult, it creates a weird power dynamic. It’s not uncommon for professional disabled dancers to have two or three years of experience and be dancing alongside nondisabled dancers with 15 or 20 years of experience.

That dynamic is something we try to be aware of in Full Radius Dance. That’s why we’ve created an apprenticeship program. As we’ve brought in new dancers over the years, apprenticeship is one way to soften the entry to the art form. Apprentices usually take company class and understudy rehearsals, as well as do outside training.

Would I like more integrated classes for kids? Sure. Are we there yet? No. Teaching disabled kids is a whole other set of skills. Wheelchair technique is completely separate, and, at this time, I don’t know anyone who isn’t a fulltime wheelchair user who can teach it. That means we have a serious shortage of teachers. Likewise with crutch technique. Teachers must also work with each individual’s physicality in a way that is socially integrated and doesn’t further other the student. Disabled adults, especially those of us who have had our disabilities our entire lives, have a certain coping ability. It’s problematic to subject a child to dance classes who might not necessarily have those coping skills yet. So it’s not as easy as saying every dance studio should accept kids with disabilities – those teachers have to know what they’re doing. Full Radius runs teacher trainings and accepts teaching students to try to get more people into the pipeline.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

I can see both sides of the question, and I come down on the side that disability dance should be assimilated into dance overall. However, there are people who will disagree with me, and point to my physical privilege that I can go into almost any dance class and take it if the teacher lets me. For a wheelchair-using dancer, a ballet barre is extremely advanced technique. There’s not a one-to-one correlation of ballet technique to wheelchair technique. Another way to think about it is, if I go into a class that is taught to nondisabled dancers, I am doing three times as much mental work because I learn the original version of the choreography, I transpose it on the fly, and then I usually keep at least one variation of the transposition in my head. Being able to do that takes practice. Since disabled dancers have different bodies, it’s not as easy as saying, “Activate this muscle.”

I would love to see more disabled choreographers too. Marc Brew is doing an excellent job pioneering for us, with myself, Alice, and the handful of other disabled choreographers of our generation making work wherever we can. Disabled choreographers don’t have to be restricted to working only with disabled dancers or physically integrated companies.

What is your preferred term for the field?

I prefer “disabled dancer.” I am comfortable with “physically integrated” as describes the dominant practice in the United States. “Disability dance,” sure. I personally do not like “mixed ability.” I feel it carries a power dynamic. With “mixed abilities,” you can quickly think of the range of abilities represented, versus the fact everyone referred to is a professional dancer. It also stems from the etymology of dis-ability, which is antithetical to our current move toward disability as identity. “Inclusive dance” is gaining popularity, particularly for recreational programs. I think that works well, but also has problems, as it’s not necessarily clear it includes disability. If you use “inclusive dance,” you need to be clear about who you are including. One of the questions that comes with that term is whether inclusion extends to people with non-physical disabilities. This is something we facilitate at Full Radius in our classes and workshops. We have not, however, had a dancer with a non-physical disability audition for an apprenticeship or the professional company.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

I’ve been dancing for more than 14 years, and I’ve seen the field grow by leaps and bounds. There are a lot of contributors to that growth, like better communication and crosspollination. As we’ve grown to have more experienced dancers in the field, we can push the boundaries of technique. That’s a lot of what Alice and I are trying to do with Kinetic Light, by asking: What can disability do as a creative force?

We were once fighting for legitimacy, to be allowed onstage at all. Now, we’re fighting for artistic acceptance.

Any other thoughts?

One question I’ve gotten recently is: Why should we have disabled dancers at all? Dance is about extraordinary physicality. As somatic researchers, disabled dancers have so many more options that haven’t been explored yet. Nondisabled dancers must find it so hard to create, because any move in isolation has surely been done. With disability, we’re still coming up with new moves all the time. It’s quite exciting to be at this frontier of wide-open somatic research exploring dance in completely new ways. It’s a key element of my practice. I’ve always been happiest in collaboration, improvising and riffing off what other people are doing. I love when one and one make four.

Pictured: Laurel Lawson, Photo by Hayim Heron, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow

Pictured: Laurel Lawson, Photo by Hayim Heron, courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow

Image description: Laurel is in her chair on a wooden stage with foliage in the background. Her chair is perched on the left two wheels while her torso counterbalances by leaning the other way. Her arms are extended above her head.

~~

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!