Elizabeth Winkelaar: “We’re Blowing Disability Out of the Water”

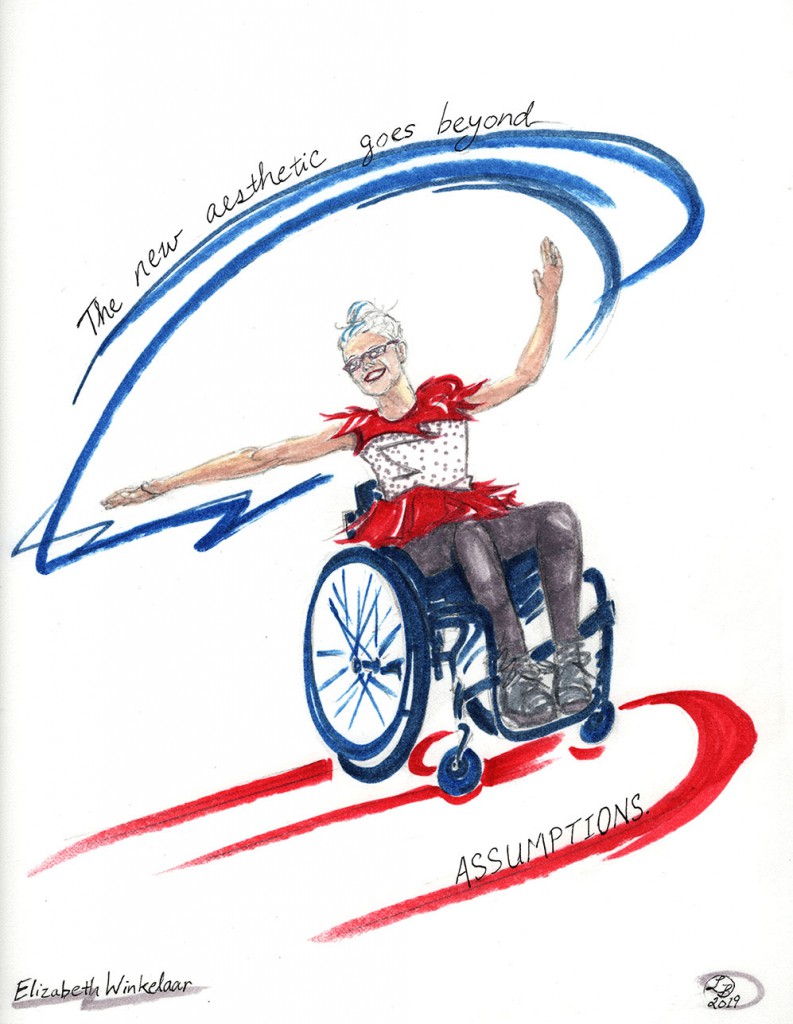

BY SILVA LAUKKANEN; EDITED BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Elizabeth Winkelaar is an artistic associate, company member, and teacher at Propeller Dance in Ottawa, Ontario. She earned a master’s degree in Canadian Studies at Carleton University, which led to an interest in disability art and culture, as well as her involvement in Propeller Dance. She has taught outreach workshops, assisted with the children’s program, and pioneered the company’s seniors’ program. She has further trained with Alito Alessi in DanceAbility, as well as with Persian dancer Maria Sabaye.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

Image description: Elizabeth is depicted sitting in her wheelchair facing diagonally toward the front of the frame. Her right arm is extended to the side, while her left is bent at the elbow, fingers raised. She is wearing a polka-dotted shirt with red ruffles at the shoulders and hips. She is smiling broadly. A blue line of energy swoops above her head and red energy pools at her feet along with the quotes, “The new aesthetic goes beyond assumptions.”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

I was always interested in dance, but I was paralyzed in a motorcycle accident when I was 18. To me, that meant the end of dance. I became a school teacher instead. I got married and had two kids. I lived a normal life. But I got burnt out. Around that same time, I got divorced after 20 years of marriage, so my life kind of fell apart at 40, and I was faced with the realization that I was disabled and needed help. I came to Ottawa, met with an old professor of mine, and said, “I need to study and understand disability.” I did my master’s degree and started my PhD, studying the political economy around disability. I was trying to research how I could prove that disability was an asset to an economy, but I started to go a little crazy with it, and I didn’t feel like I had any allies.

Eleven years ago, I saw a poster on a wall advertising a dance class. It was of Shara Weaver, one of the co-directors of Propeller Dance, and it said, “Anyone can dance.” I took the class and switched my whole life overnight. I had spent five years pursuing my degrees, but I decided very suddenly that dance was the answer I’d been seeking. I’d developed a political awareness of disability, but I didn’t feel like I was actually going to make a difference by publishing papers and finishing my PhD. I had an opportunity to be a part of Propeller Dance instead, an awesome company that now has eight dancers in addition to community classes. And now I’m an artistic associate. I found my passion and creative voice.

The next big step was making a piece of choreography, which I didn’t do until I’d been dancing for five years. The piece was called Spasticus, and it is now part of our company repertoire. It’s always changing and evolving, and I’m still learning a lot from it.

The inspiration for Spasticus came from learning about the life of Ian Dury through the film Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll and his song Spasticus Autisticus, which he wrote for the International Year of Disabled Persons in 1981. The BBC refused to play the song on the radio because they found it offensive. The song’s reclaiming of language and rejection of the charity model struck a chord with each member of the company. We created the choreography by workshopping with the lyrics and with our own lived experiences of disability. In one sequence, one of the dancers is restrained in a straitjacket. The inspiration came from the dancer’s own experience as a man with a cognitive disability.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

I’m a company member of Propeller Dance and an artistic associate. We have regular classes and rehearsals. I also teach in our outreach program. Outside of that, I’ve been studying Persian dance. My teacher, Maria Sabaye, is a remarkable woman and an expert on Persian culture. She offers me a whole new movement vocabulary. For example, the hand motions in Persian dance are very specific and meaningful. In Iran, Maria’s home, the dances she practices and teaches are illegal. She’s trying to rescue her dance traditions. I received a grant from the City of Ottawa’s Creation and Production Fund to study with her. We’ve created some duets and done some small performances. So I have this other thing going on that feeds me in a different way.

Because of Propeller, the experience of collaboration has been essential to my understanding of dance. I like to work alone, or one-on-one, but I also like the opportunity to work with visual, musical, or installation artists. That’s been very enriching. When I was in academia, I felt torn apart and isolated. I love what I do now, and I’ve never had any doubts about it.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

Confusion. A blank look. Not too many people go to the next step, but a few ask, “How do you do that?” That’s the more curious response. And then there are even some people who say, “Great, tell me more.” That’s the most positive response.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

It’s tricky with language sometimes. We keep saying again and again that it’s not about therapy, it’s about the art. Yes, of course, every one of our students – and right now we have more than 100 in our recreational and children’s classes – say dance is important to their life and has a therapeutic aspect. But we try to stress the art of dance in our classes.

With regards to press, we love when we get a review that’s done in the language of dance, instead of the language of inspiration or heroism. If the reviewer was surprised or entertained, that’s great, but when they write about the movement itself and what they saw, that’s wonderful. It’s best to avoid words like “courageous,” “inspirational,” or “brave,” but unfortunately these words are all too commonly used. I wish reviewers saw more – our strength, passion, and vulnerability. It’s hard to get reviews in general. Now we’re seeing more blogs about entertainment, arts, and culture. We’re starting to get that feedback.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

No, of course not. It depends entirely on where you live, which is so unfair. Because Propeller is located in Ottawa, Canada’s capital, there’s a lot of money spent on the arts in a politically correct way. If you want to catch some Indigenous drumming, for example, come here, because this is where money is being spent on those kinds of artists. That’s why I say it depends on where you live. I feel bad for people with disabilities who have no access whatsoever to movement, let alone dance. How are they going to find a dance class or yoga class? Whereas here, there are a lot of opportunities.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

Yes, absolutely. The time is right for that to happen, but you have to look at what that really means. For instance, more big dance companies are deciding they’re going to have an accessible space of some sort, but what are they really offering? Are they offering tea for disabled girls with the ballerina? We don’t want to get colonized. For more than 10 years, Propeller has offered contemporary dance classes for people of all ages and abilities. We have children, youth, and adult classes, always with a musician creating music for the class. We use inclusive exercises to explore space, time, balance, design, partner work, and musicality. Students have frequent performance opportunities. We have taught literally hundreds of students in the past decade. Many of these students have become beautifully skilled dancers.

There’s a new aesthetic emerging. It’s not just representing disability, but also, for example, obesity. It’s saying we’re beautiful. The new aesthetic goes beyond assumptions. It presents something the public doesn’t expect, like the idea that disabled people have sex and romance. We’re blowing disability out of the water. The new aesthetic asks the question: What does disability contribute to dance?

I’ve recently become more aware of the audience side. I’m trying to get more people of different disabilities into our audience. I’ve been networking with blind and Deaf people and finding out what they need to make that happen. Now we have a sign language interpreter.

I think we’re a long way from becoming mainstream though. I live in a happy bubble of Propeller Dance. When I look at the movies people watch, the world is a long way behind. There’s still a lot of inspiration porn. Look up Stella Young, who coined the term. We’re in a bubble where we’re pushing the boundaries of the arts world, but we don’t know how to reach the greater public beyond our audiences and students. That’s why I like the idea of digitizing our work and getting it out there. Propeller has strategic planning in the fall, and we need to find those new directions for our classes and company.

What is your preferred term for the field?

I like “integrated dance” but sometimes I also use “mixed abilities” to help people understand. Sometimes, when I say, “integrated dance,” people ask, “What are you integrating?” When I reply with the term, “mixed abilities,” that gives them the answer. Coming from someone who is visibly physically disabled, they get it. Then sometimes they’re curious about how that kind of dance works, and I like that curiosity. I think Indigenous and First Nations people also struggle with the same problem when it comes to terminology.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

Yes, we’re gaining momentum. But it’s very easy for us to fall into the trap of, “I’ve performed here and there,” and thus think that everything is getting better. It’s a much bigger project than that. Advocating for disability in dance has many dimensions. Increasingly, the big companies think they need to start integrating more. But I’d like to see them do it more mindfully and actually talk to us. Training and community outreach are important parts of the bigger picture.

Pictured: Elizabeth Winkelaar, Photo by Andrew Balfour

Image description: Liz is pictured on a blue-lit stage facing the front diagonal. Her arms are extended to the side. One hand reaches into empty space while her other hand clasps the hand of another dancer who is standing and leaning away from her. A third dancer, a man in black, is in the background. Liz is smiling and looking toward her empty outstretched hand.

~~

To learn more about Propeller Dance, visit propellerdance.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!