An Evolving Dance World

An Interview with Misa Kelly

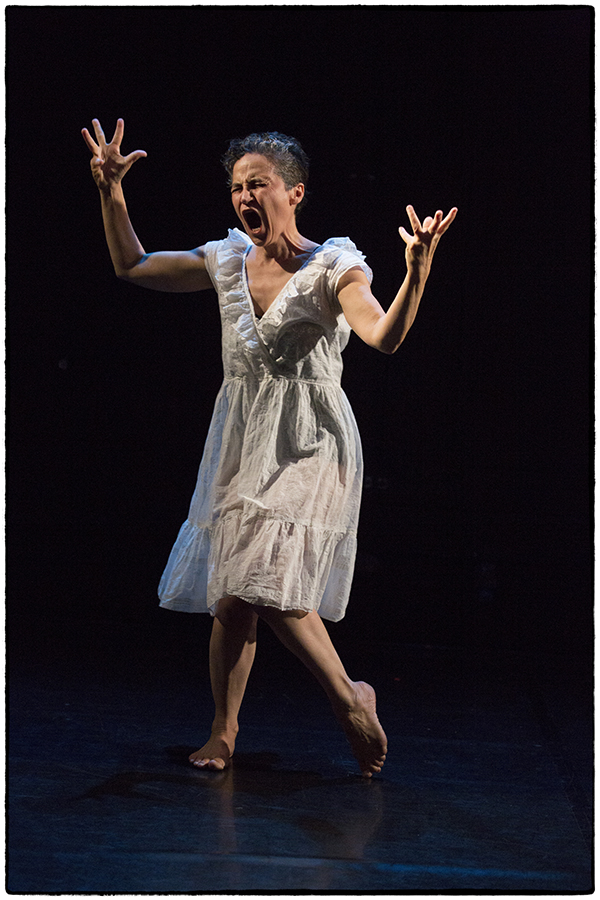

Misa Kelly is based in Southern California and has been making dances for over 20 years. She is a founder and core collaborator of Art Bark, a cross-continental dance collective. This interview is part of a series on contemporary dance and its extended implications.

~~

How would you define contemporary dance to someone without a background in dance?

Contemporary dance is kindred to sports in that it uses the body as a vehicle while others witness and experience physiological reactions. Whereas sports have rules and guidelines, in contemporary dance the rules and guidelines are different from dance-maker to dance-maker.

While a contemporary dance-maker may be competitive—and there is a competitive dance scene—in the arts it is generally not the intention to compete to win. While practitioners in both sports and dance can be viewed as elite athletes, contemporary dance draws upon aspects of the human condition not considered in sports. The contemporary dance-maker, additionally, is an innovator of forms, and may integrate sensibilities from other disciplines into their choreographic process.

A contemporary dance may be performed in a traditional theater, but may also make use of site specific venues such as parks, streets, subways, galleries, grocery stores, laundromats, and so on. Performances may also occur in informal settings such as a dance studio or in someone’s home.

A contemporary dance-maker may earn nothing, and even go so far as to pay out of their own resources to create and produce a dance. Why do we do it? Passion, purpose, life work, calling.

How would you suggest a student train for a contemporary dance career?

Training is evolving as the field of contemporary dance evolves. As one who began to dance at the late age of 28 in the 80s, my training included six years in a dance program at a university, and two years of study for an MFA. I brought to this my experience with pantomime, gymnastics, equestrianship, and adventuring on skateboards and boogie boards. I had over 150 different teachers in various movement modalities, and also attended workshops by leading figures in the field.

A traditional route would be to grow up learning how to dance in studios, major in dance, and go on to pursue a career. Some dancers may skip a degree and launch directly into a career, which is more usual in ballet than contemporary dance. The types of dancers who contemporary dance-makers use in choreography are not limited to dancers with extensive training. More and more, dance-makers work with people from all walks of life.

If one wants to make their life work being a dancer, then focusing on some movement modality is essential. Develop strong improvisational skills. Be curious, open, good-natured, easy to work with, and reliable. Retain the integrity of your body while receiving technique. Understand that the bones of ballet will serve as a springboard into anything as long as you honor the architecture of your body. Lastly, knowing arts admin skills is a plus.

It is my observation that the concept of “career” could be better framed. I would call it more of an extreme lifestyle. A life as a contemporary dance artist requires not only pursuit of one’s primary passion, but development of a tandem career which may or may not be related to dance. It is rare when a dance-maker makes their livelihood solely from dance-making.

Are there successful funding models for contemporary dance?

I prefer to think along the lines of resource acquisition as opposed to funding. If you are a contemporary dance-maker locked into receiving money to make your dances and get them out into the world, well, that could quickly prove to be exasperating.

I embrace the success of a dance-maker by their ability to entertain a vision and follow through with concrete action to bring it into a physical manifestation, be it sharing new work in a studio, producing a large festival, or touring internationally. Given this definition, I see myself and my fellow dance-makers successfully manifesting our visions every day.

I know of one dance-maker who had a daily guerrilla practice for a year in open spaces, which cost him nothing more than his time. On the other hand, I know one person who charged dancers to be in her company; they paid for classes in which they learned choreography, and in exchange they performed in locally produced showcases. I know of another dance-maker who funded her first season all out of her own pocket, and this year launched a crowd funding campaign. Another model is a local dance company affiliated with the university who has access to a plethora of resources.

Our own collective exists in a small city where there is not a single organization that funds the type of work we do. The patrons give to conservative forms such as the ballet, opera or university. Additionally, the least costly alternative for rehearsal space in my town is $17 an hour, with scant availability. The one venue that does provide subsidized space is $20 an hour. Despite the challenges, our collective has manifested amazing things. Granted, we aren’t hugely visible in the world of dance, but we are happy little clams in our orbit. Do I get paid for my efforts? Not usually, but sometimes. Does that matter to me? Not anymore. I value creative freedom, and I find I can maximize this by doing something entirely different for my bread and butter income. Would I say no to being paid every time I undertook a project? Of course not! I live in the shadow of a shoestring budget and dip into my dwindling savings to make ends meet.

How do you think your work contributes to the contemporary dance arena?

I have always been an oddball in the field of dance in my small community in Southern California. My process involves breathing in between different mediums of creative expression; some things are better expressed in written word, song, drawing, painting, photography, installation, video, sculpture or ceramics. By sourcing other disciplines, my work itself is impacted. Integrative is a word that comes to mind, which reflects my own psychological journey.

Seven years ago, I witnessed Lloyd Newsom’s DV8 in Santa Barbara, and am still coalescing from the experience. I realized technique had stripped me of something essential, and so I set out to de-dancify my body. I recently had insight into a possible modality that could be brought into an academic setting to train dance artists in a way that is relevant to where we are in time/space. It isn’t a “technique” in the sense that it isn’t created to serve my choreographic voice, and it isn’t training for a specific movement vocabulary. It is intended to serve the planet, culture, society and community. It is an integrative awareness practice. Whether this goes beyond me simply carving it out, archiving it and articulating it, I don’t know. I am just doing my part by showing up and allowing the information to synthesize and flow through me.

Another way I might be contributing to contemporary dance has to do with my relationship with the societal container in which my dance-making occurs. I’ve shed for the most part what I call the hierarchical “all about me” model with a single choreographer directing. For a period of time, I used the term “artistic director,” but I’ve always created in the context of community. My first show was co-produced with a group of choreographers.

Art Bark’s approach, developed out of a desire to create together in spite of living in different geographic regions, contributes to the field of contemporary dance in that it brings a global perspective. It harnesses the positive power of the internet to bring us closer together.

What does the future of contemporary dance look like?

Modern technology is impacting how we interact, and collaborations are easily becoming global in nature. The artists I collaborate with work independently in different cities, consult via chat, email, Skype, send recorded notes via Dropbox or upload videos to YouTube, confer on progress, refine our respective research, and then meet for an intensive session, usually one week, to flesh out the expression and either perform in an event we produce or co-produce, or participate in a showcase hosted by another dance-maker.

The nature of funding for dance is always shifting. The competitive, patriarchal and hierarchical models are antiquated. Although it may seem counter intuitive, the notion of being all-inclusive and sharing resources actually generates more opportunity than less.

With regard to the form itself, I see it possibly impacted by how our brains are changing with the use of technology and social media. When I set a dance on some SBCC students, I became acutely aware that this generation was brought up with access to technology. It seemed as if some vital component of being human was on the cusp of being lost. I felt like I had to roar in order to awaken what I sensed inside them. As our connection with nature lessens, our work changes.

I would rather not go into further detail about what I see as the future, but give my energy to being part of the now. I am currently processing a man headed to the White House who seems like a really poor match. I once thought that focusing on being an artist was the most important way I could contribute to society. I no longer hold that view. My new goal is to meet with like-hearted individuals in the studio and have move/write/sound/draw sessions that creates a safe container for processing. My thought is to harness the power of the body to source ideas and, from these ideas, to come up with bite-sized action plans.

~~

For more information, visit www.artbark.org.

First three photos by Tone Stojko; last photo by Sue Bell