Dancing the Private Lives of Pilipinx Nurses

An Interview with Kularts

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Alleluia Panis is the founder and director of Kularts, the premier presenter of contemporary and tribal Pilipino arts in the Unites States. Her upcoming production, Nursing These Wounds, is a site-specific immersive dance performance investigating the impact of colonization on Pilipinx health and caregiving through the lens of Pilipinx nurses’ history. Here, Alleluia shares the impetus behind the work and why it is as timely as ever. Joshua Icban, composer and music director for Nursing These Wounds, discusses how the piece is both personal and political, and Jonathan Mercado, a dance artist in the piece, describes why he is dedicating his performance to his mother, a former nurse.

Nursing These Wounds will be performed October 21-30, 2022, at Brava Theater Center Cabaret in San Francisco. For ticket info, visit bit.ly/ntwbrava. It was created with funding from a Hewlett Foundation 50 Arts Commission.

Photo by by Hana Sun Lee

~~

Alleluia, can you tell me a little about your dance history – what shaped who you are today?

Alleluia: I have a long history of 40 years of dance. I’m homegrown here in San Francisco. I became interested in dance only to get out of gym class in high school. From there, I met some students in an afterschool program who were taking dance through the arts commission. I’m sharing that because those kinds of entry points are important for inner city youth and youth of color. Then I started to take dance more seriously and started studying with studios in the Bay Area before going to New York for a year.

My work is rooted in community and my desire to see my story on stage. Even though I loved dancing with different choreographers, I asked myself: If I wasn’t seeing it, why didn’t I just create it? I’ve really been supported by a group of artists of color who had the same idea. That’s where the idea of creating my own work started. My biggest influence has been the lack of representation in the arts of the stories and people who look like me. I was also very influenced by Alvin Ailey’s dance company, and to this day I hold that influence close to my heart. As a mature artist now, I’ve shifted my focus toward a compulsion to create narratives and stories about my own experiences.

Alleluia, how would you generally describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

Alleluia: In terms of ideas and concepts behind my work, I’m driven by what’s keeping me awake at night. My work was never narrative in the early years, and now it has become narrative, but it’s not necessarily a dance drama. It is based in modern dance. I’ve also done a lot of Indigenous and Pilipino dance work, and in fact I danced for a brief moment with the Philippine Dance Company in New York for the year I was there. I was also trained in Philippine martial arts, and that informs my movement vocabulary. The proscenium is a friend, but I’ve started doing site specific work, in part because of COVID and the need to move outdoors.

The other thing that informs my work is ceremony. I practice the ipat from the southern Philippines. It’s Indigenous art, music, and dance as part of a meditation. It’s like an assault of the senses that gets me to a state of grace, like a prayer. I incorporated ceremony into a work I created a couple years ago during the pandemic, and I found that now I have to do ceremony in every big piece I do.

My most recent initiative is around labor and how that’s part of the immigration and colonized experience. I’m breaking down the notion of coming here with a suitcase and expanding on the forces that pushed us to seek out other economic opportunities outside the mother country. I want to understand history and the role of governments in how people move in the world. Colonization has been a huge impact. It’s that kind of unpacking, as well as removing the shame.

Joshua and Jonathan, how did you get involved with Kularts?

Joshua: I formally began working with Kularts after being a part of their 2018 Tribal Tour (the bi-annual trip Kularts had been doing for many years, bridging, and connecting artists from Pilipinx diaspora to Indigenous people, artists, and communities in the Philippines). After becoming more acquainted, I was asked to be the composer and sound designer for Man@ng is Deity, which eventually had its official world premiere this past December 2021. I was aware of Alleluia’s work before that and was hoping I could work with her somehow after being amazed by the production 6×9, which was about Pilipino/a/x people in the American carceral system.

Jonathan: I learned about Kularts after my first interaction with Alleluia in 2012 for a production called Tagabanua. Ever since then I’ve been part of a majority of her artist projects as well as her Kularts Tribal Tours. Kularts has essentially become my artistic home and family.

Alleluia, can you tell me about your upcoming piece, Nursing These Wounds, and what the impetus for the piece was?

Alleluia: I started to realize that immigration was about labor. The first immigrants from the Philippines came to the US during the early part of the last century when the agricultural industry was developing. The next wave of Pilipino immigrants was in the industries of nursing and the navy/marines. I decided to focus on the experience of nurses. When the US took the Philippines, they took over the health system and trained nurses specifically for local hospitals, but eventually they started importing nurses to the US. That’s how the idea for the piece came about. This was pre-pandemic. The initiative around labor was in 2017, and my first work looking at labor was in 2018.

Photo of Nursing class of 1929, St. Paul’s Hospital, Intramuros, Manila, Philippines: Misses Yadao, Fink, Andaya, Abuan, Peralta and Tapaoan. Photo courtesy of University of Southern California Libraries/J. Tewell.

What has been your choreographic process?

Alleluia: What I’m trying to do is explore the individual behind the labor. In California, one in every four nurses is Pilipino. The Philippines is the largest exporter of nurses in the world. But what I want to do is look at their individual stories. We did a lot of interviews and story circles with nurses, including union organizers around the health care industry. I realized we’re just talking about nurses for this piece, but there are also caretakers and technicians who are Pilipino. Because the scope of the topic is so large, I decided to focus just on nurses.

We had nurses show me how to put on PPE, so some of the choreography was drawn from nursing movements, but they are human beings beyond being workers. Through the interviews, I realized most of the nurses are immigrants or the children of immigrants. There’s often intergenerational conflict between a Philippines-born nurse and an American-born nurse. I’m looking at those differences and commonalities.

For example, in the piece we have a hospital scene, but we also have a party scene to show that nurses don’t only exist in hospitals. I also have projections that help with the narrative, as well as text that was generated based on the interviews. The closest thing to a narrative in this piece focuses on why they became nurses.

Alleluia, why is investigating the impact of colonization on Pilipinx health and caregiving through the lens of Pilipinx nurses’ history relevant or important to explore now?

Alleluia: It was relevant before the pandemic. I’m not dealing directly with the pandemic with this piece, but people are going to infer that because of our reality right now. This story has been happening since at least the 1960s, and it’s still relevant. There’s so much to explore just about the industry in general. This is the first iteration, and I hope to develop it more next year.

Joshua and Jonathan, does Nursing These Wounds resonate with you personally, and if so, how?

Joshua: Nursing These Wounds is personal to me as my father was a nurse. His path coming to it was from the US Navy but the circumstances of his immigration and settlement here in the United States nonetheless was influenced by the same colonizing history between the Philippines and the United States. Though nursing is an essential and honorable profession, and more so now in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, it doesn’t seem to be common knowledge why such a big percentage of nurses in the United States are of Philippines descent. It’s treated as a gag now, but nursing has become the profession many parents of Pilipinx children push their kids to pursue. I believe it is vital for this generation to really examine the roots of why this is and ultimately how that trend not only comes from this country’s need for care workers but is deeply rooted in the American history of exporting human bodies for labor.

Jonathan: Nursing These Wounds does resonate with me personally, namely because my mom is a nurse and many of my family in the Philippines are in some sort of medical field. Throughout my entire life, I witnessed my mom coming home late, working at two hospitals at one point, and always having ICU stories to tell at the dinner table or whenever we got a chance to get picked up by her from school. She was always learning, digging herself into her books, taking seminars, and teaching folks along the way. As glorious as it all sounds, there was so much sacrifice. Her energy was always spent in service of others and that’s where she found purpose and joy for herself in life. She has since retired in 2020 within the beginning of the pandemic. I dedicate my performance in service to my mother and the sacrifices she had to make for us to live a better life through her pursuit in the medical field.

What do you hope audiences take away from Nursing These Wounds?

Alleluia: I hope the audience comes away with an understanding of the long, difficult, and challenging history that continues to this day. And that nurses are individuals. Nurses have become more relevant because of the pandemic, but pre-pandemic, there wasn’t a depth of understanding that these people face difficulties. Hopefully it will ignite their curiosity to look beyond the career to see the human and their needs.

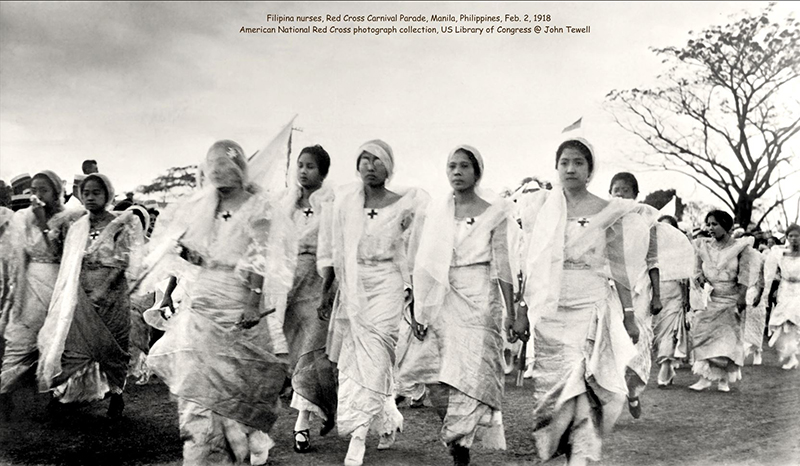

Filipina nurses, Red Cross Carnival Parade, Manila, Philippines, Feb. 2, 1918. American National Red Cross photograph collection US Library of Congress/J. Tewell

Joshua: I hope that audiences take away a new perspective of this very complex profession. I’d like to think with the ongoing reality model our world is designed to follow, one cannot enjoy luxury without it being at the expense of another, and what I’m seeing shift in these current times is a reckoning and hopefully re-imagining of this. I hope too it can help to achieve a greater appreciation and awareness for the many stories that are people’s actual lived experiences.

Jonathan: For the show as a whole, I hope that people get a glimpse of the hardships that nurses face. For my character however, I hope that people take away that you’re never alone, that our spirits and ancestors guide us in whatever path we take and when we most need it.

Any other thoughts?

Alleluia: My work is informed by Indigenous belief in the sacred mysteries; dance can be a powerful connection to ancestral energies. Dance – and all forms of art practice – is a form of meditation and prayer. The practice of ritual or ceremony, like ipat and kanggwana, is a huge influence on my creative process.

Many of the dancers and collaborators in the production are related to nurses, whether it’s their grandmother, mother, sister, or aunt. It’s very close to home.

~~

To learn more, visit www.kularts-sf.org.