Isabel Cristina Jiménez: “Dance is Freedom”

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; TRANSLATED BY LORIEN HOUSE; FACILITATED BY BRENDA POLO; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Isabel Cristina Jiménez is a plastic artist and butoh dancer in Bogotá, Colombia. Isa graduated from the Academy of the Arts Guerrero-Bogotá in 2014, where she studied plastic and performative art. She was introduced to butoh in 2010 by Ko Murobushi, and has studied with Brenda Polo, director of Manusdea Antropología Escénica. She has participated in various butoh laboratories including, in 2014, a residency at Casona de la Danza. In 2016, she won the Bernardo Páramo prize. She also participates in solo and collective art exhibitions; in 2017, her work was exhibited in Pascual Noruega.

Listen to the audobook recording of Isabel Cristina Jiménez’s interview here!

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

Para leer en español, desplácese hacia abajo. (To read in Spanish, please scroll down.)

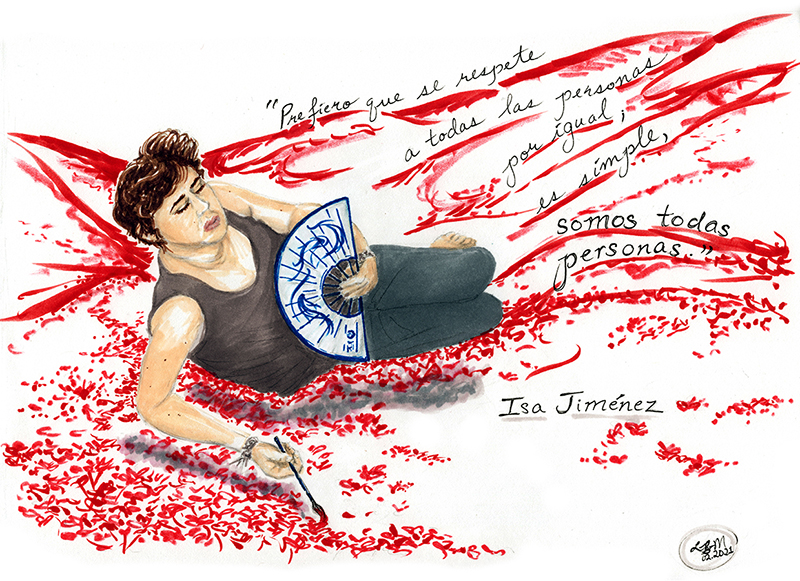

Image description: Isa is depicted lounging on her side propped up on her right arm in a hillside of red which she is painting with a paintbrush in her right hand. Her left hand holds a blue fan to her chest. The quote, “Prefiero que se respete a todas las personas por igual; es simple, somos todas personas” (translation: “We should respect everyone equally. It’s that simple; we’re all people.”) sits on the red hills.

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

I took my first butoh workshop in 2010 with Ko Murobushi at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. The workshop was called El Poder Oculto de la Memoria (The Hidden Power of Memory). In the workshop with Master Ko, we jumped, fell on the floor, laughed, and hugged each other. I especially liked the exercise called “the feline,” where everybody walked around as if we had one eye in our heads. In another exercise, we dropped to the floor as if dead, and then watched each other from the viewpoint of death. Many of the exercises were hard for me, but I did them the best I could.

In 2012, I participated in another butoh project called Chaturanga Hamlet at the Academia Guerrero. We started the creative process with Professor Juan Manrique by drawing on square pieces of wood in black and white ink. Then we assembled a chessboard out of the drawings, which we used in the dance. Each one of us moved on the chessboard like the different chess pieces. We used white makeup on our faces and hands – Professor Adriano applied it with his airbrush. It tickled! Professor Ximena Collazos did our costumes, dressing us in black plastic with red tulle on our heads.

In that project, all the women played the role of Ophelia. Ophelia throws herself to the floor, opens her jewelry box, and begins putting on her jewelry. There were a lot of movements associated with the jewelry scene. Ophelia hides her face with her Japanese fan. We (the Ophelias) said: “I’m crazy with love,” and, “They have broken your heart,” as we pulled our hair with our hands and ran around the stage on tiptoe. My hair was short, so I pulled it as much as I could. Then we fell, as if fainting, and our princes cried for us. Sixteen of us participated in Chaturanga Hamlet. It was a wonderful process. A lot of us fell in love – me with Caliche (Carlos Rojas) for example. In 2013, Carlos and I got more serious, and we’re still together.

Chaturanga Hamlet was presented in Bogotá in the Academia Guerrero at the Teatro Libre. I was a little nervous; it was my first time in a theater. But my co-performers and I pulled together and concentrated, and when we entered the stage and began to move, the nervousness left me completely. We also presented it in the Zona T – a street in Bogotá – and in the Teatro del Ágora in the Academia Guerrero.

In 2014, we did a nine-month butoh residency and performance called Odds (which stands for “opportunity” or “advantage”) in the Casona de la Danza in Bogotá. We worked with Victor Sánchez, Lorna Melo, Ximena Feria, María Teresa Molina, Nicole Tenorio, Fernando Polo, and Brenda Polo. The training was very difficult. I often got up at 4:30 a.m. in order to get to the studio by 7:00 a.m. We jumped, did turns in the air, practiced the “prayer,” the “egg,” and the “worm.” We fell to the floor. We explored what it was like to disappear into the windows. We experienced the feeling of being trapped. We sweat a lot during the practices!

The residency was hard for me, but I didn’t give up. My colleagues helped push me. But in fact, I didn’t want to stop. Every day I felt better. I loved jumping, feeling the tremble in my body, feeling good energy, concentration, breath. I felt free. We left each practice exhausted and sweating, but happy with what we’d done. The residency was also good for my work in the plastic arts – I painted two butoh dancers during that time.

In 2017, we did the performance La Metamorfosis with a grant from Bogotá Diversa for the group En-Trance. There were 30 of us – different ages, from different areas. There were even some children from a foundation. And a lot of people with diverse abilities. We helped each other constantly. There was always someone to help a person in a wheelchair by carrying them up to the third floor (there was no elevator), or helping those who had visual impairments climb those stairs each day.

We’d arrive at practice and immediately make a circle on the floor, each one of us in a star position (arms and legs extended) with feet touching. We’d breathe deeply together. There were people in wheelchairs, people with crutches, people with visual impairments. It was wonderful dancing with them and learning from them. For example, I used a blindfold in order to move without being able to see. I felt dizzy, and a little scared, but not much. With my eyes blindfolded, I could actually feel more.

We did our first performance in front of the Museo Nacional de Colombia. Later, we performed in the Plazoleta of the Universidad de Jorge Tadeo Lozano. The freedom I felt when we performed in the street was wonderful. There were so many emotions at once: moving my body, feeling the space around me, being outside, and performing alongside my friends. We all felt so happy doing this creative work together!

Our next project is called El Agujero Negro. We’re going to start it online at first, because of COVID-19. I’m anxious to move again and to feel that freedom again!

How would you describe your current dance practice?

I practice butoh with Brenda Polo. I also draw and make paintings. For me, both are important. Dance is a form of therapy for my body, because it makes me feel more alive, energetic, and free. And then I like to express those experiences by painting the human figure – nudes and dancers, and my life in Colombia. In my work you can see a lot of paintings of dancers, especially women.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

People congratulate me. They say: “What beautiful dancing. I like your dancing!”

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

If I see a person dancing in a wheelchair or with crutches, I think, “These people can dance. They can feel their arms, their bodies.” Seeing people with different capabilities dancing is cool. It inspires me to continue my practice.

People who don’t know anything about dancers with disabilities might be surprised to see them dancing, but they’ll also feel proud. They might feel freedom. They’re going to have positive responses.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

There aren’t many in Bogotá. I think we need more classes for people with different abilities – for example, those with wheelchairs, those with visual impairments. And I think classes should be for everyone together, regardless of different abilities, not separated into this or that group.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

Yes. Having mixed groups enriches everyone. I also think that grants and scholarships should be for everyone, regardless of ability, and that everyone participates together. What’s important is the person, and what she wants to achieve. People with different abilities and no money can also dance and achieve their dreams with much success.

What is your preferred term for the field?

I don’t like “disabled” [“discapacitada” in Spanish]. I’m a normal person like everyone else, so I don’t like that word at all. We should respect everyone equally. It’s that simple; we’re all people. I prefer “diverse capabilities,” or we can call it “inclusive dance.” I don’t like terms like “lame” or “crooked” either. They’re horrible. I don’t like the discrimination I feel in those terms.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

Yes, there are more opportunities than before, but I wish there were even more.

Any other thoughts?

For me, drawing and painting are like therapy. But dancing is different. Dancing is feeling my body, feeling the vibrations. Dance is freedom. It’s a unique sensation. Now that we’re unable to go out and dance together due to the quarantine, I really feel that need.

When I can’t dance, I feel discriminated against. It’s like a form of bullying – it makes me feel trapped, like I can’t move. There’s no movement in my body, no vibration. When I can dance, I feel space and freedom.

Isabel Cristina Jiménez, Photo by Ernesto Monsalve

Image description: Isabel leans into the frame and smiles. Her face is painted white and she has a big red bow tied atop her head. Other people and lights are blurry in the background.

~~

To learn more about Manusdea Antropología Escénica, visit www.manusdea.org.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

This interview was conducted in March 2020.

~~

Isabel Cristina Jiménez Tenorio: “Bailar es Libertad”

Isabel Cristina Jiménez Tenorio es una artista plástica y bailarina de butoh ubicada en Bogotá, Colombia. Isa (nombre artístico), se graduó de la Academia de Artes Guerrero-Bogotá en 2014, en donde estudió artes plásticas y performativas. Se introduce en la danza butoh en el año 2010, con el maestro Ko Murobushi, y ha continuado sus estudios con Brenda Polo, directora de Manusdea Antropología Escénica. Isa, ha participado en varios laboratorios y obras de butoh, incluyendo, en 2014, una Residencia Artística realizada en la Casona de la Danza. En 2016 fue ganadora del premio Bernardo Páramo con la obra “Secuestrados y Mujer Desplazada.” También ha realizado varias exposiciones de arte individuales y colectivas, en el 2017 expone en Pascal Noruega.

~~

Por favor, cuéntanos un poco sobre tu historia con la danza. ¿Cuáles fueron algunos de los puntos más memorables de esta historia?

Mi primer taller fue con el maestro Ko Murobushi en el año 2010, en la Universidad Nacional de Colombia. El taller se llamó, El Poder Oculto de la Memoria. En el taller hicimos varios ejercicios de butoh, como caminar muy lento, brincar, hacer caídas. Nos reíamos, nos abrazábamos. Me gustó mucho el ejercicio del “felino” – todos caminamos como si tuviéramos un ojo en la cabeza. En otro, caímos al piso como muertos y nos miramos del punto de vista de un muerto. Muchos ejercicios eran difíciles para mí, pero los hice como pude.

En el 2012, participé en otro proyecto de butoh que se llamó Chaturanga Hamlet en la Academia Guerrero. Primero hicimos un proceso creativo con el profesor Juan Manrique, dibujando con la tinta china negro y blanco sobre pedazos cuadrados de madera. Ensamblamos un tablero de ajedrez con los dibujos, y lo usábamos en la obra. Cada uno caminaba como un personaje de ajedrez diferente. Nos maquillamos de blanco la cara y las manos; el profesor Adriano de aerografía nos maquilló a todos con su aerógrafo. Fue divertido, hacia cosquillas. A nosotros nos vistió la profesora Ximena Collazos con el plástico negro y el tul rojo en la cabeza.

En el Chaturanga Hamlet, todas las chicas hicimos la persona de Ofelia. Ofelia se tiraba al piso, abría su joyero y se empezó a colocarse sus joyas. Había muchos movimientos acerca de esta escena de las joyas. Con su abanico japonés, Ofelia se escondía el rostro. Decíamos: “Estoy loca de amor,” y “Te han roto el corazón.” Nos cogíamos los cabellos con las manos hacía arriba y corríamos de puntas por todos lados. Yo tenía el cabello corto y también lo estiraba para arriba. Después, nos desmayábamos y nuestros príncipes lloraban por nosotras. Éramos 16 compañeros de la Academia quienes participamos.

Fue grande ese proceso. Varios compañeros nos hicimos novios—yo con Caliche (Carlos Rojas). En el 2013 Caliche y yo ya fuimos más serios. Hasta ahora (2020) somos novios.

Chaturanga Hamlet fue presentado en Bogotá, en la Academia Guerrero, en el Teatro Libre. Yo tenía un poquito de nervios; era mi primera vez en un teatro. Me fui a concentrarme junto con mis compañeros. Cuando entré en la escena y empecé a moverme, se me acabaron los nervios. También nos presentamos en la Zona T—es una calle de la ciudad de Bogotá—y en el Teatro del Ágora de la Academia Guerrero.

En 2014, hicimos una residencia de butoh de nueve meses que se llamó “Odds” (que significa: oportunidad, punto de ventaja), en la casona de la danza en Bogotá. Trabajamos con Víctor Sánchez, Lorna Melo, Ximena Feria, María Teresa Molina, Nicole Tenorio, Fernando Polo y Brenda Polo. El training fue muy duro. Madrugaba mucho a las 4:30 a.m. para llegar a la casona a las 7:00 a.m. Brincabamos, hacíamos giros saltando. Practicábamos la plegaria, el huevo, el gusano, y las caídas al piso. Explorábamos desaparecer en las ventanas y sentirnos atrapados. ¡Sudábamos mucho en las prácticas!

Fue duro para mí, pero no me rendí. Mis compañeros me animaron, y yo tampoco quería dejar mis prácticas. Cada día me sentía mejor. Me encantaba hacer los brincos, sentir el temblor del cuerpo. Sentía la buena energía de la concentración y la respiración. Me sentía libre. Salíamos cansados y sudando, pero contentos de haber hecho esta práctica. La residencia también fue bueno para mí creación en las artes plásticas—incluso pinté un par de bailarines butoh.

En 2017, hicimos el performance Las Metamorfosis, con la Beca Bogotá Diversa del grupo En-Trance. Fuimos unas 30 personas. Veníamos de distintas partes y éramos de edades diferentes, incluso habían niños de una fundación. Y personas con capacidades diversas. Nos ayudábamos unos a los otros—siempre había alguien para cargar a un compañero y su silla de ruedas hasta el tercer piso (no había ascensor), o a ayudar a los compañeros invidentes a subir al tercer piso.

Cada día cuando llegábamos, hacíamos un círculo tendidos todos en el piso, en posición de estrella (con brazos y piernas abiertas), todos conectados hasta los pies. Respirábamos hondo, juntos. Había gente con silla de ruedas, con muletas, invidentes. Fue lo mejor bailar con ellos, y aprender de ellos. Por ejemplo, yo usaba la venda (en los ojos) para andar sin poder ver. Y sentía mareo, y un poco de miedo, pero muy poco. Teniendo los ojos vendados yo podía sentir más.

Hicimos el primer performance en frente del Museo Nacional de Colombia, y luego en la Plazoleta de la Universidad de Jorge Tadeo Lozano. La libertad de salir a la calle para la performance era genial. Me sentía muchas emociones a la vez, moviéndome el cuerpo, sintiendo el espacio, estando allí con mis amigos. La pasábamos felices por el encuentro y el trabajo creativo.

Mi próximo proyecto se llama El Agujero Negro. Y vamos a iniciarlo en línea debido al COVID-19. Porque quiero moverme, ¡quiero esta libertad de nuevo!

¿Cómo describirías tu práctica del baile actual?

Practico el butoh con Brenda Polo, y también soy artista plástica. Dibujo y pinto cuadros. Para mí, las dos cosas son importantes. La danza es una forma de terapia para mi cuerpo, porque me siento más activa, enérgica y libre; mi cuerpo se siente más vital. Me gusta expresar estas experiencias pintando figuras humanas, basadas en el desnudo, en bailarines, y la vida que tengo en Colombia. Entre mi obra tengo muchas mujeres bailando.

¿Cuáles son las respuestas más comunes que recibes cuando dices: “Soy bailarina.”?

La gente me felicita. Me dicen: “qué bonito danza. Me gusta su danza!”

¿Has encontrado problemas con la manera en que la gente habla, o ve a las discapacidades en la danza?

Si, yo veo una persona con alguna diversidad física en el baile, como una persona en silla de ruedas o muletas, yo pienso: “estas personas pueden danzar. Pueden sentir sus brazos, su cuerpo.” Y ver a estas personas bailar es chévere. Me anima a seguir con mis prácticas.

La gente que no sabe nada de las discapacidades, tal vez van a estar sorprendidos viendo estas personas bailando, pero también orgullosos de verlas. Pueden sentir una sensación de libertad. Este baile va a tener respuestas positivas de la gente.

¿Crees que hay oportunidades suficientes para el entrenamiento de bailarines con discapacidades? Y si no, cómo se puede mejorar?

No hay muchos lugares en Bogotá para eso. Yo creo que debemos tener más oportunidades para tener las clases, para gente con capacidades diferentes—por ejemplo las personas con silla de ruedas, o invidentes. Y pienso que estas oportunidades deben ser para bailar juntos, no separados.

¿Entonces prefieres que los bailarines con capacidades mixtas se asimilen más en el “mainstream” (baile “convencional”)?

Sí. Tener grupos mixtos es enriquecedor para todos. Y yo prefiero que las becas para talleres, etc., sean para todos y que participemos todos juntos. Porque, lo que importa es la persona y lo que ella quiere lograr. Hay gente pobre y con capacidades diferentes en todos lados y también ellos danzan, cumplen sus sueños y triunfan con mucho éxito.

¿Tienes un término preferido para la escena de la danza con discapacidades? Y, por otro lado, hay términos que no te gustan?

No me gusta la palabra “discapacitada.” Soy una persona normal como otras, y no me gusta que me digan nada de eso. Prefiero que se respete a todas las personas por igual. Es simple; somos todas personas. Prefiero, “capacidades diversas.” O pueden decir que nuestro “baile es inclusivo.” No me gustan términos como cojo, tuerto, chueco. Son horribles. No me gusta la discriminación que se ve en estos términos.

En tu opinión, ¿está mejorando la escena de la danza con respeto a las capacidades mixtas?

Sí, hay más oportunidades ahora que antes. Pero me gustaría si fueran más todavía.

¿Hay alguna otra cosa que quieres decirnos?

Para mí, dibujar es una terapia total, lo mismo que pintar. Pero bailar es distinto. Bailar es sentir el cuerpo, sentir la vibración. Bailar es una sensación de libertad. Es una sensación única. Y ahora que estamos súper encerrados (por la cuarentena de Covid-19) con mayor razón quiero danzar.

Si, yo no pudiera bailar, me sentiría discriminada. Es una forma de bullying—el pensar que no podemos mover nuestro cuerpo. Me hace sentir atrapada, como si no hay movimiento en mi cuerpo. No hay vibración. Cuando bailo, siento que tengo espacio y libertad.

Foto de Ernesto Monsalve

~~