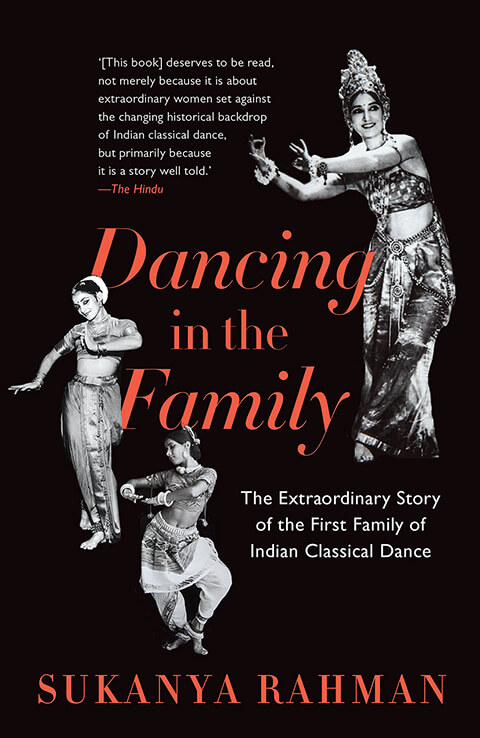

Three Generations of Indian Dance Pioneers

An Interview with Sukanya Rahman

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Sukanya Rahman is an Indian classical dancer, visual artist, and writer based in Maine. In 2019, she published her family history, Dancing in the Family, which details the history of her mother (Indrani Rahman) and grandmother (Ragini Devi), both icons of Indian classical dance. The incredible story starts with her American born and raised grandmother leaving her Minnesota white family to pursue Indian dance in the 1920s, and takes the reader on a wild international ride across borders, experiencing political upheaval like WWII and the Partition of India, and navigating the throes of family drama, all in the name of dance. Here, Sukanya reflects on what resonance her family’s story continues to have.

Indrani, Ragini and Sukanya at the Three Generations’ Performance, New York University Theatre; September 29, 1978

Photo: George Shakespear © Sukanya Rahman/Ram Rahman family archives

~~

Can you share a little about how and why you came to write Dancing in the Family?

I always had this crazy family story, so it was always in the back of my mind to write about it. All through knowing my grandmother, I kept asking questions. Her answers were always fantastic. She was an American from Minneapolis. To become an Indian dancer and live most of her life in India was quite extraordinary. I got down to writing after she died when we got her papers, letters and albums. I also wanted the story preserved for my children. Now my grandchildren are interested. It was really for them, though people would also ask me questions: where are you from, what do you do? I thought it would be much easier to write it down than repeating the story over and over.

What was your process? You mention in the forward that your mother was open about her story but that there was a lot of mystery surrounding your grandmother. How did you go about unearthing her story?

I learned about my grandmother from her letters. I don’t know how anyone can write a book these days without letters, since people have switched to sending emails. That was my most precious resource. She had also written books on Indian dance dating back to 1929. There was a lot of dance information in her books, though she didn’t reveal too much about her personal life. She’d mention traveling with a nanny while my mother was a baby, and my mom would say there was no such nanny. I had to sift through a lot.

The book was in gestation for many years and had many incarnations. I found a publisher through a university press, but they were trying to turn it into an academic book. My mother was alive then, and she and I felt it should be a family story. It should be a human-interest story, not a dance history, though that creeps into the book as well. It took a long time. Now it’s in its third publication, and I hear from the publishers it’s doing well.

How did writing the book inform your own sense of self, either as an artist or just as a person? Did you come to better understand part of your own story through writing this?

Not really. I just did it without thinking of myself. It was really the process of telling the story.

You wrote of your grandmother’s budding love of Indian dance: “She came to understand that Indian dance was a form of worship and not entertainment” (page 21). I’m curious your thoughts on how to value and appreciate other cultural dance forms than our own?

When we performed in the US, the audience reaction was loving it for what they see. I felt that the audience understood the spirituality of the dance. If a performer really dances from their internal experience and not as entertainment, it comes to the audience in that way. That being said, there’s nothing wrong with being entertained by the dance.

Much later in my career, I had a small grant from the NEA to study with a master guru in Bangalore. He was descended from a tradition of musicians and dancers attached to a temple in Tanjore. The experience was most enriching. At one point, my guru asked us to travel from Bangalore to Tanjore to his village temple. I went with my husband and children, and I danced in front of his altar, which was in his house attached to the temple. His whole family were temple musicians and dancers. That day, I performed for no audience, just laundry and cows. I danced in front of the small altar for Krishna, and my guru was singing and chanting for me. At that moment, I realized what our dancing was about. These dances were performed in the inner sanctum of the temples when the deity wakes up, is bathed, is fed. It was part of worship. I danced on a mud brick floor with a dip in front of the images on the altar. My guru said the hole has been formed by hundreds of years of dancers stamping on that spot.

Earlier in my life, I studied with Martha Graham. One of the things she would tell us that never left me was, “Whenever a dancer stands ready to perform, that ground is sacred.” If a beautiful dancer performs from his or her soul, the audience feels that. I have felt that watching many dancers. Both my mother and grandmother raised me and my brother watching performances. They always said we should tremble and weep and shake and burst into tears if something really moves us. That’s when the dance has meaning. I also experience that feeling with film, music, art – it’s all sacred. It’s how one perceives something and how one is moved, no matter one’s religion. It’s more a question of spirituality.

Indrani in her first Orissi costume, 1958

Photo: Habib Rahman © Sukanya Rahman/Ram Rahman family archives

Do you see your grandmother as partaking in some form of cultural appropriation, or is that an anachronistic reading? I ask this especially since she passed herself off as Indian at the beginning of her career, though she also helped develop an appreciation of classical Indian dance and music internationally.

That thought never struck me. I took her for whom she was. Growing up, we were surrounded by lots of crazy artists. Those questions never arose. I just took people for whomever they were.

I found it interesting how you wrote that as an adolescent you resented your mother’s all-encompassing devotion to her art and wished she would be more “normal,” and yet later in the book you expressed gratitude that you didn’t have a normal mother and grandmother. Did these experiences affect how you approached your own home/work balance once you became a mother?

I never planned on becoming a mother. It sort of happened, and I took it in stride. We have two boys who are four years apart. Our life was a complete zoo. When you’re a dancer, you do everything at the same time. You can’t wait until your children are off at college to start a career. We would drag them all over the place, traveling with my mother and husband, all in it together. I never had time to question anything deeply. I went from day to day. It was survival. It was crazy and I’m sure my kids would have liked a more normal childhood, though with what they are doing now, maybe we did something right.

Both of them did not want to be artists. They wanted to make money. It was always a struggle trying to get grants. People are always asking artists to do things for free, like give free performances and workshops. But my sons got a good education, and now they are off on their own and doing well. Now my granddaughter is making noise about studying dance. If she truly wants to, I’ll devote myself to that.

Do you have a sense of what your grandmother’s and your mother’s legacy is? Is it tied to a certain place or time? Especially since you now live in Maine in the US, how do those legacies continue from your perspective?

The whole dance scene has changed drastically since their days. It’s much more prolific and all over the place. I told you about the values of performance I learned from my grandmother and mother, but I don’t get that sensation when I go to see a performance these days. I see it more as entertainment now. There’s been huge exposure to Bollywood and people are more interested in being entertained. My grandmother and mother were certainly pioneers in the field and did a huge amount to bring the dance to the public. Once those foundations were laid, there were few performers, but they were all extraordinary and individual, even in the same styles. There was originality; their costumes and approaches were different. This is something I miss now. It’s much more mechanized. There are still some beautiful things to watch, but a lot of that is more in folk dance and martial arts, which aren’t being presented yet as just sheer entertainment.

What do you hope readers take away?

I hope they get the history, what my parents and grandmother contributed to the arts. The new generation has not heard of a lot of the dancers mentioned in my book. I want readers to get a sense of how the three of us – my grandmother, my mother and myself – really pursued what we wanted to do deep down without any question of money. Everything was done on a shoestring. In those days, it was possible, and we did it. It’s more difficult now. Dancers now need a backup job to survive. It’s not an easy field.

Any other thoughts?

For ten or 12 years, I was a consultant with the NEA and traveled all over the country monitoring individual dance artists who were applying for grants. That was an eye-opener. I watched not only Indian dancers, but also modern and ballet dancers. I saw the struggle. Of course now, the NEA has stopped funding individual artists. Even when I got the grant to study in India with the guru, we stretched it. The government had shut down, so I went without any cash, and my husband and children followed. We were staying in a tiny place in Bangalore with very little money. Finally, we got a message that the money had been sent to the American Consulate in Madras. My husband took the train overnight and got the money, which was all in cash, and had to stuff it in his pockets. Coming back on the train in third place, his pockets were bulging. We were finally able to pay some of our bills.

In India, it’s just as hard as in the US to be a dancer, and it’s getting harder, especially now with this pandemic. My heart goes out to dancers and any artist whose life is performing onstage. People are doing things virtually, but it’s still a tragedy.

~~

To order Sukanya’s book, visit here.