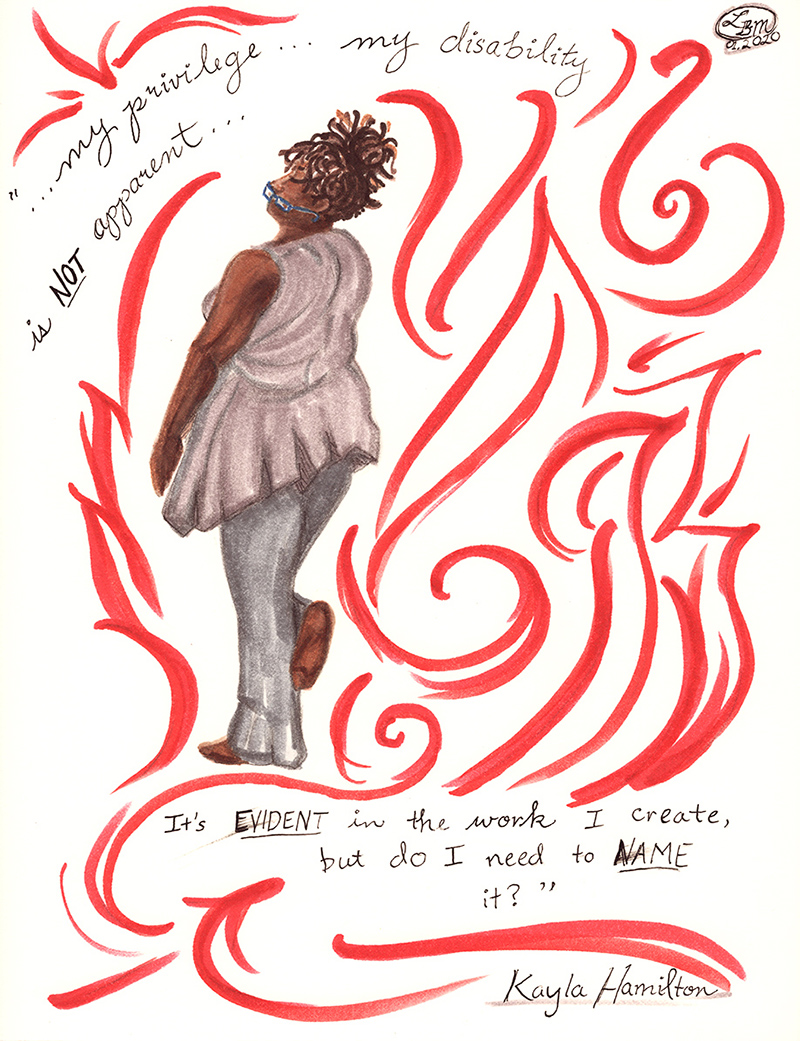

Kayla Hamilton: “Do I Need to Name It?”

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Kayla Hamilton is an artist, producer, and educator originally from Texarkana, TX and now residing in Bronx, NY. She earned a BA in Dance from Texas Woman’s University and an MS Ed in Special Education from Hunter College. She is a member of the 2017 Bessie-award winning cast of Skeleton Architecture, and dances with Sydnie L. Mosley Dances, Maria Bauman-Morales/MBDance, and Gesel Mason Performance Projects. She teaches master classes around the US and received Angela’s Pulses’ Dancing While Black 2017 fellowship. Under the name K. Hamilton Projects, Kayla self-produces her choreography, organizes community events, and writes arts integrated curriculum.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

Image description: Kayla is depicted standing in the left upper corner of the image facing back and looking over her left shoulder. Her eyes appear closed and blue glasses hang low on her face. Her right foot is hooked behind her left calf. She is wearing gray. Red swirls of energy decorate the space around her, along with the quotes, “…my privilege…my disability is not apparent…” and, “It’s evident in the work I create, but do I need to name it?”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

When I was about three, I was watching television and my parents noticed that I sat really close to the screen to see it. They took me to a doctor, who told me I have amblyopia. Basically, my left eye was severely near-sighted. In order to see, I needed to get really close to things. Growing up, I knew my glasses were super thick and I went to the eye doctor frequently, but I didn’t realize my sight was different than my peers. My parents put me in dance as a way for me to be active and not feel different than other folks. I took basic ballet, tap, and jazz in middle-of-nowhere northeast Texas. I fell in love with it.

I went to school and got my bachelor’s degree in Dance. Immediately after undergrad, I produced my own concert before I moved to Washington DC. It wasn’t a requirement, but sort of a capstone. I wanted to do something before leaving my home state. It was entitled Running with Myself.

I was in DC for a few years. A highlight was producing another show called Shift: Choreographers Taking Flight. I brought out one of my professors from undergrad to perform with some graduate students. Then I transitioned to New York City, where I am now. Here, a highlight is dancing with Skeleton Architecture, a group of Black female and gender-nonconforming performing artists. Another highlight was winning a Bessie award for outstanding performer as a part of the collective.

Then there was DoublePlus at Gibney Dance, which was curated by Alice Sheppard. I shared the evening with fellow disabled artist Jerron Herman. It was beautiful and magical; I get teary just thinking about it. I’m at a place in my life where I’m starting to recognize my disability and acknowledge it as part of my identity. For so long, it had not been until complications started to compile. I began to think, “Oh shit, this is real. There’s no hiding behind it.”

Finally, I was part of I Wanna Be with You Everywhere, a festival curated by and for disability artists. It included writers, poets, and dancers. I choreographed and performed as part of a shared evening with Alice and Jerron. Although we performed separately, it was so powerful to have three Black disabled bodies sharing the space.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

I don’t really take modern dance class anymore. I find there’s a lot of spatial anxiety with taking modern dance classes; I get disoriented being upside down or doing floor work. Plus, I’m just not that into it. I do take traditional West African dance class multiple times a week.

Right now, I’m focusing more on choreography. I’m interested in asking questions about surveillance and how it strips and heightens our identities, especially in the context of Blackness, gender, and disability. I’m also interested in interrogating intersections of race and disability: Is Blackness performative disability? How do we de-center sight as a primary source of consumption? Are there different ways of using description of aesthetic and accessibility? Where’s the push and pull of traditional description? Many descriptions are what I consider to be technical, dry, and boring. I created a piece where I’m doing the same movement over and over again but describing it each time in a different way.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

That’s where my privilege as a disabled artist lies; my disability is not apparent. Most people find out about my disability after they meet me.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

I find that people make assumptions not connected to my disability, but with my body type. Although times are slowly shifting, I still don’t look like a traditional standing dancer. I am a larger body; I have 36 triple D boobs and wear a size 18 or 20 in pants. However, people don’t associate me with having a disability, whereas someone who uses a wheelchair might face preconceived notions about what they can and cannot do. People only find out about my disability later when we go somewhere and I have to hold their hand tightly. They’ll notice and I’ll say, “Yep, can’t see.”

With regards to press, I would suggest to just describe what it is that you see. Take away your preconceived notions. The goal of the writer is to uplift the artist. It carries so much weight in our field. Focus on the mood, the feeling, and the conceptual aspects of the work, not on whether you can imagine yourself doing that if you had that disability. No one cares.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

Hell no. Teachers who don’t identify as disabled need training so when a disabled student walks into their classroom, they’re not like, “WTF.” Here in New York, there’s Gibney Dance that supports physically integrated dance as part of its broader programming, but disabled dancers need our own training center or institute. Disabled artists need to be teaching, and not only other disabled artists. Buildings need to be accessible. People who do not identify as disabled need some literacy about what to do when disabled bodies come into the room. And most of all, again, we need our own education centers.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

That’s a hard question. There must be some level of rigor, push, talent, and challenge in disability artists to function in non-disabled dance spaces. If I were a ballet dancer, I personally would not go into American Ballet Theater, for example, because I can’t do what they can do. They have a long history and tradition of doing things a certain way. If a disabled artist can do something that satisfies the demands of the highly codified techniques of ballet or that particular company, then go ahead. If not, why don’t we create our own spaces? That way, we can invite others in, rather than trying to enter pre-established spaces.

This happens with different identifiers: Blackness, queerness, etc. They become the only one in that community or space and then become tokenized. This becomes another set of issues.

What is your preferred term for the field?

I’m still figuring this out for myself. I don’t like “handicapped.” “Mixed abilities” sounds a little crazy to me too since we all have a mix of abilities.

As someone acknowledging my identity, it gets confusing. I’m not sure what’s appropriate and what’s not appropriate. Which communities use which terminology? I know for myself what I prefer, but if I’m around other disability artists, I’m less sure what to say. Because my disability is non-apparent, I’m not sure where I land sometimes within that community.

I just re-wrote my bio; one version says, “visually impaired dancer,” and another says, “disabled dancer.” I’m not sure if it’s necessary to put disability forefront. I don’t put “Kayla Hamilton is a Black, fat, female dancer…” You know what I mean? It’s evident in the work I create, but do I need to name it?

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

Yes, I do think so. Things are popping up. Grants are becoming more available and sometimes accept video and audio instead of just being in written form. People are acknowledging that not everybody accesses information the same way. Residencies are also popping up. Curatorially, our voices are starting to matter more, and people are acknowledging we deserve to be heard. I think we are making progress.

Any other thoughts?

For me, having Alice Sheppard in my life as a mentor and someone to look to as a model has been instrumental, especially as I step into my own identity and in terms of my artmaking. She in particular has been instrumental in the push and challenge I’m going for in my artistic practice.

Photo by Travis Magee

Image description: Kayla is standing on a sidewalk with buildings and cars in the background. Her feet are wide apart, and her arms and hands are by her chest as if she is pushing something away from her. Her hair flies around her face. She is wearing jeans and a sweater. The photo is in black and white.

~~

To learn more about Kayla’s work, visit www.khamiltonprojects.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!