Charlene Curtiss: “They’re Missing the Best Part”

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Charlene Curtiss, founder and director of Light Motion Dance Company in Seattle, has been choreographing, performing, and teaching integrated dance since 1985. Charlene has taught dance at the University of Washington Medical Center and Harborview Medical Center, as well as performed in various national and international venues. Her work has been featured on NPR, NBC’s Today Show, ABC News, CNBC, CNN, PBS, Reuters, and Seattle television stations. Her original dance technique in front-end chair control redefined the choreographic terminology of integrated dance. She is also a licensed attorney.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

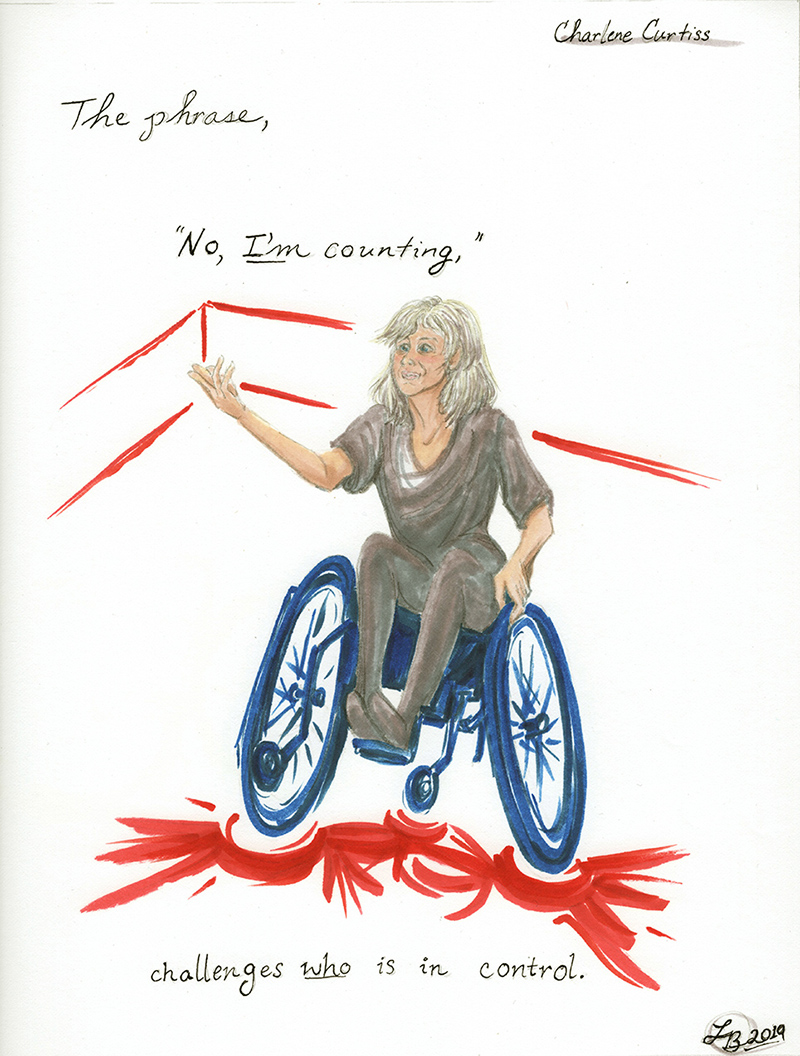

Image description: Charlene is depicted facing the front left diagonal of the frame in her wheelchair, her right arm extended palm up in front of her. She is wearing gray and her blue wheelchair rests atop red swishes of energy with the quotes, “The phrase, ‘No, I’m counting’ challenges who is in control.”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

I was a gymnast before I was injured in a gymnastics accident in 1968. For a few years after my injury, I walked with crutches and short leg braces. Then I slowly got involved in wheelchair sports, but the idea of dancing hadn’t occurred to me. In the 80s, I went to Rio de Janeiro where I met this Brazilian man who had these drummer friends. I was with them when this big lightbulb went off in my head. We were on top of some mountain with this wonderful breeze. They were playing incredible music on drums, and I started moving my upper body and arms. I got carried away and had a wonderful afternoon just exploring movement. When it was all over, my friend said to me, “That was a long time coming back, wasn’t it?”

When I got back to the states, I started working with my wheelchair on a technique I call front-end chair control. It explores movements with the front end of the chair off the ground. I eventually hooked up with my dance partner, Joanne Petroff, and it all went from there.

There have been hundreds of highlights. The Peabody Institute, a conservatory for music in Baltimore, contacted me in the early 90s to do a project together where I would control the music with the movement of my chair through sensors on my chair and body. Different notes were connected to different movements, which then created sounds. The composer worked with me to design the choreography in order to create the sounds we wanted to hear.

We did so many unique shows. Atlanta Ballet asked us to set a piece on them. We combined some of the wheelchair dancers in Atlanta with the stand-up dancers in the ballet company. We also performed internationally – Russia, Australia, Ireland, Portugal, Canada, and Mexico.

There were three different festivals of integrated dance we were invited to that were just getting started in those years. One was in Atlanta at the Paralympic Games, one was at the Boston International Dance Festival, and the third was in Los Angeles at the VSA Art & Soul Festival. What was so exciting about those festivals was seeing other integrated dance companies because, in Seattle, we were pretty much it.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

Things have changed in the past five years for me. I’ve had a couple of surgeries and my dance time is nothing like what it used to be, but we are still dancing and teaching. We do more teaching now, which is rewarding in and of itself. What I’m doing to stay fit is an upper body workout and stretches, and of course dancing. I used to swim, but not so much anymore.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

The reactions have not changed much over time. There has always been a perplexed look. If I just say, “I do integrated dance,” people don’t know what that means, so I have to tell them what integrated dance is and how it works. Unless they’ve seen it, they still don’t grasp it. I tell them, “You’d like what I do if you saw it.”

We did a performance last year and I heard a comment I’d heard before years ago. The audience member came up to me and said, “I didn’t see the wheelchair in your piece.” They’re trying to say it as a compliment, but I think they’re missing the best part.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

Joanne and I plus another dancer we work with, Debbie Gilbert, used to go on tour through the schools and give shows or lecture demonstrations. I remember one teacher coming up to the three of us but only talking to Jo and Debbie, even though I was right there, and telling them how great they were to include me, even though a lot of the choreography was mine. We decided that when stuff like that happened, Jo and Debbie would defer people to me. We even got in the habit of me giving an introduction and sometimes running lead as a way of taking away the opportunity for the disabled person to be seen as being politely included.

Then there’s the inspirational narrative. What disabled dancer doesn’t run across that? Over the years, my response to that has changed, ebbed, and flowed. Sometimes, I’ll respond, “I think you’re such an inspiration.” I’ll turn it back on them. When I was an athlete doing wheelchair sports, stand-ups always wanted to turn me into the super girl who was an inspiration. That has changed in sports because people are more familiar with wheelchair sports. But they are not familiar with wheelchair dance, so people still feel inspired. I suppose it’s good they’re inspired, but are they inspired because of the dance itself or because a disabled person is doing it? And yet is there really a difference?

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

Absolutely not. Adding classes at the university level would be a really good start, although dance departments so rarely have faculty who can teach integrated dance techniques. There are many dance techniques that are common to both mainstream and integrated dance, such as counterbalance. Still, most of the quality wheelchair dance instructors work in the private sector, typically as part of a professional integrated dance company. Several of those professional companies offer classes on an ongoing basis, such as AXIS in the Bay Area, Dancing Wheels in Cleveland, and Full Radius in Atlanta. Light Motion, along with Whistlestop Dance, offers classes periodically as drop-in workshops or as part of an educational residency in the schools in the King County area. An ongoing weekly class where students could simply drop in on a regular basis gives dancers the best opportunity to learn.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

It’s great to have festivals that are all about showcasing integrated dance. Those are unique and extraordinary experiences. But integrating dancers with disabilities into the mainstream is also very important and shows something else: It highlights equality, acceptance, and new ideas.

Integrated dance has finally risen to the level where we can start being critical about it. Some of it’s good, and some of it’s bad. It’s not “all good because it exists” anymore. There’s finally enough integrated dance that we can start to have critical dialogues, and people who have an educated eye for integrated dance can initiate those dialogues. My husband is one of those people. He’s been watching integrated dance for decades and can call it when it’s good or when he doesn’t like it. But a lot of people who are unfamiliar with integrated dance wouldn’t dream of saying it’s not good. I think that’s an important step.

What is your preferred term for the field?

I don’t like “handicapped dance.” I don’t really get caught up in whether it’s “mixed abilities” or “integrated” dance. It’s not so much about what it’s called so much as what it is. They started calling it “physically integrated” to differentiate between physical disability and mental disability. That becomes important when you’re trying to advertise for a public workshop, because you don’t want to misrepresent what you can offer.

It’s difficult to come up with a language that encompasses so much, so we just have to continue to explain.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

Of course it is and it’s very exciting. However, there doesn’t seem to be as many festivals showcasing integrated dance companies as there used to be. Maybe I’m just not as aware since I travel less now. It got to where I just hated flying! There’s also less funding in the arts. On the other hand, there are certainly some spectacular companies, both nationally and internationally, doing wonderful work.

One performance I saw in Boston by Candoco Dance Company had a quadriplegic dancer on the floor, on purpose, who was getting ready to get back into his chair. Two stand-ups came to pick him up – one under his arms and one under his knees. One of the stand-ups started to count, “One, two, three” to signal when to lift. The wheelchair user interrupted, “No, I’m counting,” and then counted very slowly to test them, “One… two… three.” Then they picked him up. This became a tagline for Jo and me for years. The phrase, “No, I’m counting,” challenges who is in control. It’s so vital in integrated dance.

Who’s in control especially comes up in choreography. Jo and I co-choreographed everything. If she wanted to do it one way and I wanted to do it another, we would dance it out until we found the best workable solution. As a result, our choreography was well-balanced. When a stand-up dancer comes in and tries to choreograph by saying, “This is how it should be,” they’re wrong half the time. Movement that works is obvious, but movement you have to fight with to make it work is obvious too. When integrated dance companies teach and/or perform, the audience can see the equality of the movement, and that’s the education they gain. It changes people’s perspectives.

Any other thoughts?

Integrated dance is an extraordinary and exciting career path. I feel very fortunate to have found my way into the field. It’s been so very rewarding for so many years.

Photo by Richard Ross

Image description: Charlene is depicted leaning back in her wheelchair over the back of her dance partner, who is in a lunging crawl. Charlene’s arms extend above her torso and above her head. Both dancers smile at the camera. The photo is in black and white and the two dancers are wearing unitards.

~~

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!