Making Work from A Military and Māori Perspective

An Interview with Maaka Pepene

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Maaka Pepene is a dance artist in Aotearoa/New Zealand and a choreographer for Atamira Dance Company, a Māori contemporary dance company. Here, he described his choreographic process and some of the themes that guide him, as well as how his background on the streets and in the military inform his values and approach.

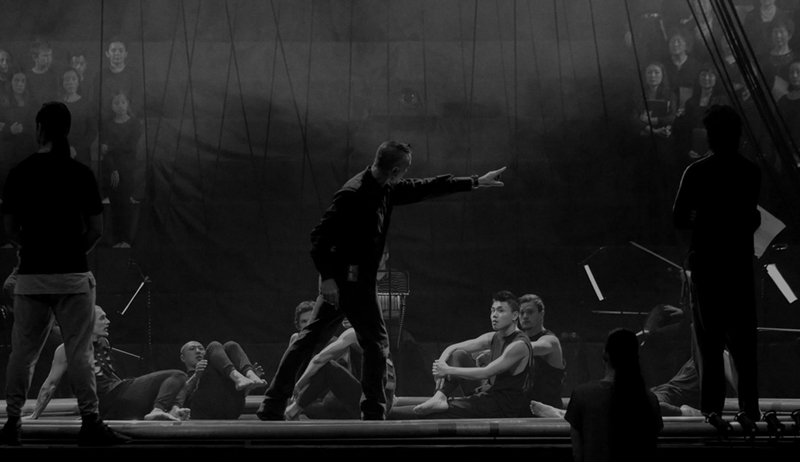

Photo by Matt Gillanders

~~

Can you share a little about your dance history – what kinds of performance practices and in what contexts shaped who you are today?

I started dancing when I was 25 or 26 after I left the army, and I was trained in contemporary dance by some amazing New Zealanders, such as Douglas Wright and Michael Parmenter. In the early 90s in a place like New Zealand, the contemporary dance scene was quite new. People thought I was a stripper when I told them I danced, and it became challenging to explain. I did martial arts and also spent a lot of time on the streets and picked up that body language, even though I am contemporary trained. It became easier to call myself a movement technician in the sense of taking any movement and expressing myself through it.

My first language was Māori so, growing up in a predominantly Pākeha city, I was shy expressing myself verbally. Instead, I was quite physical with contact sports and martial arts, as well as street fighting, crime and drugs. I joined the military to get away from all that. I was trained as a rifleman, but I was predominantly a scout and a tracker, so I did very physical activities.

In the army, it was easy to be focused and directed. After the military, I was directionless. After being turned down from a job, I saw a notice on a bulletin board for a government-run school teaching dance Monday through Friday for six months. I applied, got in, and discovered the freedom of expression.

One of my teachers told me to be more sensual in my movement. I thought she meant sexual, so I had to look up what ‘sensual’ meant, which was ‘affected by or pertaining to the senses.’ I could relate; as a scout in the army, I had to be aware of my surroundings by using my senses.

I became a member of Taiao Dance Theatre, which was part of the renaissance in Māori arts in the late 80s and early 90s. My wife, Justine Hohaia, was one of the founding members of Atamira Dance Company. I would go along to help and eventually started dancing there as well. A lot of our dance companies in New Zealand are pickup companies, so the small community of dancers go from one company’s project to another. I’ve danced with Touch Compass, Auckland Dance Company, Black Grace and Pacific Sisters. The first time I choreographed a piece was in 1992, but really, I started choreographing as soon as I started dancing.

Photo by Matt Gillanders

How would you generally describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

What drives me is honesty and truthfulness. I give ownership to the people I work with, so they give 200 percent. I try to give as much information to get everyone onboard with the concept of the work, so we can be as truthful and honest as possible.

The early part of my life was about survival. The essence and detail it takes to survive on the streets forces you to be a chameleon. The best performers are those who can transport themselves and move through different worlds. We’re fortunate in Māori that we are able to move through worlds, our own and Pākeha dominating society. I think that’s what has helped contemporary Māori today. They’ve been able to merge knowledge and move forward. As human beings, we either evolve or die.

What does your choreographic process look like?

My process is what I’m feeling strongly about just in daily life. An idea sits in the back of my head and starts wanting to be pushed out. I start writing and talking about it, getting a clear idea of what the seed is. Justine is a big part of the process; we sit and talk. We come from different places and have different points of view, so she can help to clarify and act as a sounding board.

From there, I start researching. It’s important to get as much information as possible, since knowledge is power. It took me awhile to realize that. I love research and learning. Once I know what the seed is and research it, I find what is relevant and what is not. It starts to grow like a plant.

When I get with my collaborators, I give them a lot of information. I’d rather give too much information than too little. I try to get them as invested as possible. The great thing about working with different people is we all have different processes. I like seeing information from a different perspective.

In the military, you don’t get that kind of conversation. It’s been like that in different companies I’ve danced in as well. Once I get with the collaborators, the process is driven by honesty as well as being aware that the seed may germinate into something else.

The movement is there from the beginning. Indigenous storytelling doesn’t delineate between dance and song. The idea and the movement all start at the same time. Sometimes the movement even comes first. It might be a pedestrian movement, or just the light of a moment. I’m not even aware of it sometimes. There’s an improvisational element as well. Improv comes from trying to find what that original feeling was, the essence of it.

Photo by John McDermott

Are there certain themes or issues that feel important to you to keep tackling or addressing in your work?

What is pushing me along at the moment and has for a few years is the idea of hope. If we don’t have hope, we don’t have the possibility of evolving. In all societies today, we have suicide, illegal drugs, inequality, and intolerance of others. Hope keeps pushing me forward, because otherwise I wouldn’t be here today. I’ve been to the depths on my own personal journey, and I still see the good around me.

We live in a small village down the end of a peninsula with two Indigenous meeting houses, called marae, where people come together. There’s a whole physical connection to living here. We can go fishing off the rocks just a few minutes away. These are my wife’s tribal lands. Learning from the elderly people informs me as well. It all forms what interests me and what I’m working on.

Is there a specific piece in your repertoire you’d like to share more about that you feel is a good representation of your work?

My first full length work was called Memoirs of Active Service, which expressed my time in the military. It wasn’t about the fighting itself; it was about the in-between time. I wanted to honor not only my time in the military, but also my grandfather’s time in the military in WWII, as well as families and veterans of other conflicts.

The essence of the work is a love story about my grandparents and their longing for each other during the conflict. I am the guardian of my grandfather’s diary from WWII. The choreography is based on the diary, some of which I created to keep the flow of the story going. It starts before the war with common folk and sheep shearers coming together. I establish the characters in the work: three men and two women. The men represent father, son, brother and husband, and the women represent mother, daughter, sister and wife. I establish them before the war in their community, and then the war breaks out. There was one battle scene, which I called butoh haka. The rest of the vignettes were in between fighting, as well as showing the roles the women had to take on in the men’s absence.

Photo by Kathrin Simon

It was satisfying personally to tell these stories and be as honest about them as possible. A big part of the work was how songs bring us together and lift us in the darkest times. The responses from audience members afterward were incredible. It made lots of people cry.

My other full-length work, Te Houhi, was about the knowledge of why we are the way we are. With Indigenous people, we have wanted to go back to our ancestral lands and ways of life, while others have looked down on us and said that was so long ago. Those people don’t understand how that disenfranchisement has affected Indigenous people today. My grandfather was protesting the land that was taken illegally. Trauma becomes intergenerational. One of my tribes recently received an apology from the government for what happened to our people. For example, we were called “sinful people.” When you are called something like that for a period of time, the effect is huge. Te Houhi was about trying to understand my people’s truth and express why these challenges are in front of us.

What are some shifts (if any) you’ve experienced with regards to representation of Indigenous/ Māori voices in dance?

It’s an interesting question in part because of where I live. Auckland is a four-hour drive from my home, so I don’t see much contemporary Indigenous/ Māori arts right now, and I don’t go online often. However, I used to work backstage at a big venue where I’d see the same show over and over. It made me ask why I liked or didn’t like different aspects of the performances. I got to see a lot of different works from around the world and, from that perspective, I think contemporary Māori art is in a good place. It’s progressing and being challenged. Movement is in the curriculum at schools, so it’s become more acceptable. There has been a shift.

When I started teaching workshops at schools through various companies, there’d be the ballet mums with their kids in leotards and jazz shoes, and then there’d be the lower income kids from single parent families or abusive situations, who I’d try to connect with through hip hop, breakdancing and capoeira, which a lot of them were into. Since I used to be one of those kids, I wanted to let them know there are so many options out there, so give it a go. It comes back to hope. We need it more so today than ever.

What’s your next project? What are you working/focused on now?

As part of a new work with Atamira, I’m going to this idea of iwi, which is like a tribe but also the bones of a body. I’m using it from the vantage point of stripping back to the bones. We have bad problems and it affects all levels of society and our environment. We’re stripping away the essence of the land. It all goes hand and hand, the body of the planet and the body we live in.

I don’t think of taking my work out into the world beyond my sphere of influence. For me, it’s just about storytelling. In most Indigenous cultures, myths are huge. They are guidelines for what we should do. I’m not just talking about for people of color; I’m talking about people throughout millennia. It’s okay if a story reaches only one person. I’m not trying to target a huge audience; I’m just trying to express myself.

Photo by Serena Stevenson

~~

To learn more, visit atamiradance.co.nz.