Experiencing the Body as Physical Resource

An Interview with Olive Bieringa

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Olive Bieringa is the founder and a collaborator alongside Otto Ramstad of BODYCARTOGRAPHY PROJECT, which creates dance in urban, domestic, wild, and social landscapes, and whose work is rooted in experimental dance, somatic and socially engaged practices. Olive is a choreographer, director, performer, somatic movement therapist, video artist, producer and curator from Aotearoa/New Zealand, currently based in Norway. She is a registered ISMETA somatic movement therapist and educator, a certified practitioner and teacher of Body-Mind Centering®, a Shiatsu practitioner, and a certified DanceAbility teacher. Here, she discusses the scope, themes and values of her dance practice.

action movie at Weisman Art Museum, 2018, Photo by Boris Oicherman

~~

Can you tell me a little about your dance history and what kinds of performance practices have shaped who you are today?

I grew up in New Zealand in a home that was immersed in the visual arts. I was always making stuff but, in terms of the possibilities of what dance could be, my options were limited. It wasn’t until I left and started traveling that I learned about experimental, improvisational and somatic dance practices. The desire to study the body and movement propelled me out of New Zealand. I had thought I would just paint and make sculptures, but I wanted to do something with my body while I was young.

I discovered in the Netherlands two very experimental dance schools that were operating in the early 90s. I ended up at one of them, CNDO, what later became the European Dance Development Center, in Arnhem just outside Amsterdam. For four years, different guest teachers would come in and work with us intensively. The focus of the work was experimental and post-modern. I have a degree in improvisation and composition. In the frame of that education, I became interested in the materiality of the body, the relationships between my body and another being’s body, the differences we have, and how our experiences are informed by what we perceive is possible.

When I came out of school, I was interested in how what I had been studying in dance spaces and private spaces might make sense in the context of the larger world. I started sharing practices in pubic spaces. I returned to New Zealand after living in the Netherlands, Israel and London. I was trying to make sense of all this evolution and learning that had happened within me, as well as trying to make sense of how I could share some aspect of that with my community in New Zealand. It’s incredibly beautiful there. I didn’t want to spend all my time dragging people into the theater. I wanted to bring dance practices out into public spaces and get people engaged and excited about the work. Examples of that kind of early thinking and practices included teaching a lot, having contact jams in public spaces such as in business suits in the middle of the city, a slow motion walk down a mountain dressed in orange, or working with some of Lisa Nelson’s Tuning Scores to build an ensemble practice that could play itself out in different urban spaces. My work became about finding ways of creating a bridge between the inside and outside of the body, transforming our perception of the city, what was possible in public space, and what we defined as dance.

felt room in rehearsal, Photo by Presley Zigos

I eventually moved to San Francisco because I felt like I didn’t want to be alone at that moment with all my experience in New Zealand. I wanted to be part of a larger community of movement researchers and dance makers more aligned with my curiosity. I discovered the world of integrated dance while attending a Diverse Dance Research Retreat on Vashon Island outside of Seattle, an event created by Karen Nelson and her collaborators. Diverse Dance was a weeklong event where about a third of the participants were differently abled. There was no structure other than mealtimes. We would live together and dance together. People would propose research or facilitate a workshop or warmup in addition to having different care roles and responsibilities. It was an amazing opening experience for me. Going to that got me into a much broader question about the possibilities of dance and movement research that I wanted to unpack.

I met my partner Otto Ramstad at Diverse Dance. He and I have a shared aesthetic. He was wandering around in Minneapolis with a blindfold on doing experiments with his senses. I asked, “Why are you doing that by yourself?” Together, we had a very aligned appetite around making, experimenting and looking critically at site specific work. We are also quite dedicated to the practice of improvisation. And here we are 20 years on.

How would you describe your aesthetic to someone unfamiliar with it?

We make lots of different kinds of things, so I’ll just describe some of them. The first piece, action movie, might be invisible to the surrounding public. One audience member and one performer take a walk through the city, an art museum or on a frozen lake. action movie is a practice in making magic through the simple act of walking and opening and closing our eyes. The performer guides the viewer, mostly through touch, inviting them to open and close their eyes at specific times through the use of the calls “open” and “close.” The performer plays with the texture and speed of the touch and the calls to reveal the surrounding landscape through different perspectives. Sometimes the dancer is the protagonist inside the visual frame of the audience. Sometimes the audience member experiences the stillness and movement in the world. The piece invites us to explore how touch, sound and vision function in the construction of a dance, in this case a very intimate one. action movie creates a context in which we can be present with strangers, nonverbally, and have a deeply embodied experience as performer and as viewer.

Undoing the hegemony of vision as a way to reverse the epistemological phenomenon of what we experience as “truth” is an important concern of several recent works. A realignment of the balance of our senses is a condition for the world to show itself to us on its own terms and is also a wake-up for our consciousness. Experiencing the world in all its dimensions opens what we define as real and true.

felt room at the Weisman Art Museum, 2018, Photo by Boris Oicherman

Another example is felt room, an installation for a gallery space. It’s a four-hour long work with five to seven female performers inside of it, and it was conceived of as a dance for the dark. However, in order to have darkness, there must be some light, so there are deep saturated colors that build and shift the perception as well as a complex multi-channel soundscape. The work cycles every hour through a progression of dark and light as a way to refresh our ability to perceive darkness and transform our seeing. The dance is meant to be felt and heard as much as seen. We’re again looking at all the things dance does underneath creating space for a visual image; how do we use kinesthetic empathy to read what is happening? Touch is an underlying key to much of what we do as dance makers, so how do we share that with the broader culture?

Otto has been developing Lineage, which recently premiered at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. It is a story-telling and dance work with video installation and a larger studio practice around it. He is looking at questions of place and his relationship to his family lineage in Norway looking back four generations. How can he use his dance practices and Body-Mind Centering to learn about his lineage and build a relationship with these people and places?

We make performances, films, installations and festivals. There’s a huge blur between our movement and artistic research, teaching and performance making. There’s a question of how pedagogy becomes a performance, or how to use materials used in a Body-Mind Centering context to bring the audience into their bodies. All these works do that either through language or through the transmission of movement to facilitate a physical experience.

Are there certain themes or issues that feel important to you to keep tackling or addressing in your work?

On a really simple level, one theme is about development and the materiality of who we are. We have all this physicality in our structure that is an incredible resource without imposing other information on top of it. Another theme is how we literally grow ourselves; we develop kinesthesia and touch first, then smell and taste, then hearing, and seeing is last. As we develop, each of those senses brings us higher up in our brain. The high brain changes how we see the world and experience life. It can become quite abstracted. Dancing allows us to hold complexities by getting out of binary thinking and exploring ideas about time, space and place through movement while in our tissue. Perhaps these aren’t themes per se, but principles or values that have become primary in what we make. For example, we’re working on a new project on embryology for art and science museums. We’re moving back in time to embody our embryological development, which allows us to move into the future in a different way. There’s a process and logic that underlies this outrageous thing – that we can time travel – which we can do through our tissue at anytime.

Place of Space residency for embryology project at the Weisman Art Museum, 2018, Photo by Boris Oicherman

Why is knowledge of somatic modalities like Body-Mind Centering important for dance artists?

There is all this resource in our bodies, especially if we’re not only thinking about dance as something we do through imitation – though imitation has value because it’s one way we learn movement and language as infants. I feel that Body-Mind Centering allows me to move between sensation, memory and imagination in a dynamic way. It not only feels good but also helps me move with recognition of my choices and movement patterns. It helps me recognize what else is possible and helps me realize that sometimes the choices I make aren’t always the best choices, and that I can make other choices. It allows me to be generative as a dancer, maker and performer. That level of refinement can happen by tapping into different aspects of my body systems.

What’s your next focus?

We’re working on a big project in Oslo in September called Togethering. It’s a bit of a retrospective because we’re returning to a bunch of one-on-one and tuning score practices for public spaces. We’re doing it in our new city as a way to bond with the place and people and potentially transform the behavior in one neighborhood.

The embryology project, which right now is called the museum of fluid spaces, has just received support from Kulturadet, the Norwegian arts council, and will go into a medical museum and art museums as an installation. That work might take the shape of a 10-day radical embryology laboratory, for example. Dancers and scientists will be sharing the space, having performances, workshops and conversations to create a heightened learning environment. It feels like an installation for a museum context, but also a classroom, dance studio and theater.

~~

To learn more, visit bodycartography.org.

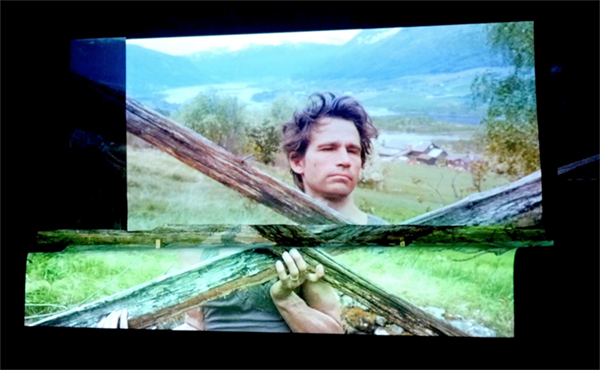

Lineage video still, Otto Ramstad, 2018