Teaching Robots to Move, Let Alone Dance

An Interview with Amy LaViers, director of the RAD Lab

Amy LaViers is the director of the Robotics, Automation, and Dance (RAD) Lab at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The lab seeks to leverage embodied, choreographic practice in the development of expressive robotic systems and in the study of human motion. Amy and her team work to build machines that help, extend, and move in harmony with people. Here, she shares her thoughts on how dance can inform how to make robots move more effectively.

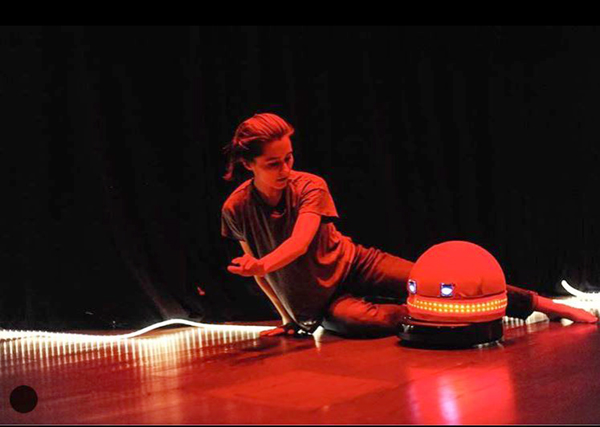

Amy LaViers performing alongside the DD robot platform in Time to Compile (www.timetocompile.com) at the Granoff Center for Performing Arts at Brown University at the Conference for Research on Choreographic Interfaces (CRCI) in March 2018; credit Keira Heu-Jwyn Chang (@SpatialK).

~~

Can you share a bit about your own history and how you came to combine dance and robotics?

I grew up dancing and was a member of the Tennessee Children’s Dance Ensemble before going to Princeton University to study dance and engineering as an undergraduate. My interest in robotics began when I connected the field to choreography. In a course on dance writing, I saw a clip of Twyla Tharp discussing her work with two different styles of dance. I realized then that the quantitative tools in my mechanical engineering courses, particularly those in dynamics and control, were analyzing the same thing: patterns of bodies moving through space and time.

How did the RAD Lab come about?

I started the Robotics, Automation, and Dance (RAD) Lab after finishing my PhD at Georgia Tech in my first faculty post at the University of Virginia (I’m now at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). Both these schools are research institutions where faculty teach alongside building robust research programs funded through government, industry, and foundation grants and contracts; the RAD Lab is my research group. I’ve always known that the lab would include robotics and dance, and I added the term “automation” as a broader idea of what a robot is. I’m in a minority of roboticists who subscribe to the idea that a paperweight is a robot. Moreover, I notice that the term “robot” does not have scientific roots (I discuss this with my collaborators from the arts in this paper), and I always want my group to treat robots like the machines and tools that they are; hence, the broad idea of “automation” is an important grounding concept for the lab.

Can you elaborate on one or two of your favorite projects that have come out of the RAD Lab?

Every project in the lab bolsters and grows the others: I cannot pick favorites!

A project that dance artists may enjoy learning about – which has fractured and grown into many subprojects – is my collaboration with Catie Cuan, a dance artist who has recently relocated to the Bay Area to study mechanical engineering at Stanford. This project began with Catie’s residency in my group and has become an active research project and startup company. We’ve toured a piece, Time to Compile, which has both a live performance and interactive installation component. Within these presentations of the work, we’ve also collected data from audience members who elect to participate in a research study. The work has been published at a few conferences with two culminating journal papers in progress.

Links to learn more:

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-05204-1_49

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-05204-1_40

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8525520

https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=3212888

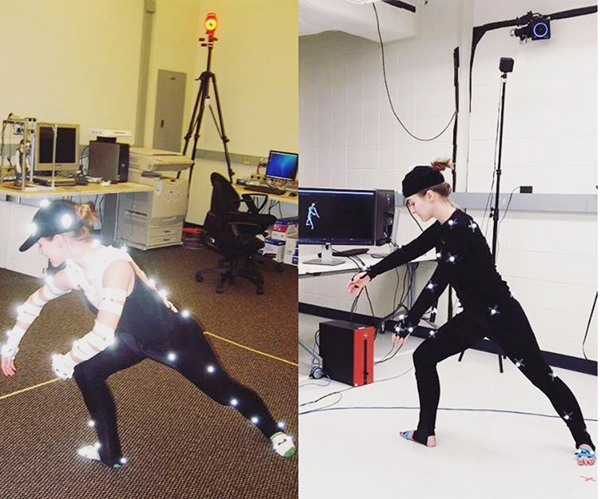

Catie Cuan and Amy LaViers in the RAD Lab in July 2017 during the lab’s annual summer workshop; credit: Riley Watts (@eberginger) who was also teaching at the workshop along with CMA Catherine Maguire.

Another project, one that is reaching the end of a phase, is that of my most senior PhD student, Umer Huzaifa. He has developed a simulation of planar biped that generates forward locomotion, creating variable motion styles with a novel, core-located source of actuation. This design has also been prototyped by a team of undergraduates under Umer’s leadership. This project shows how gait – even on artificial systems – communicates information to human viewers, which, as dancers well appreciate, is highly variable depending on context. This is a sort of unusual finding in robotics, given that many researchers aim to apply affective labels, e.g., happy and sad, directly to artificially generated motion trajectories. In my group, we are working to extend prior work, adding nuance to such models with a descriptive taxonomy inspired from Laban/Bartenieff Movement Studies. This approach is also informed by my experience writing about dance, where descriptions of movement have to be paired with culture and context to understand a particular piece.

Links to learn more:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12369-019-00514-1

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/7523617

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/7523618

What are some of the biggest limits in robotics that you’ve come up against?

The movement of machines! Machines do not move like humans, and we don’t totally know why. I write about this more here.

How can robotics inform dance in ways one might not expect?

I write about one aspect of this in a recently published book here. My chapter discusses how formalized models for style of motion can give a backboard, of sorts, for dancers to bounce their ideas off, hopefully generating new ones. In this particular chapter, the formal model I discuss is a finite state machine, which represents a strict discrete ordering of motion that I have used in artistic performances to specify motion sequence for dancers and machines.

Conversely, how might dance inform robotics in ways one might not expect?

Dance provides an informative lens and critical set of technical tools for roboticists. Dancers are technical experts in the process of making meaning (for humans) out of movement. As robots move out of the factory, we want their motion profiles to inform human viewers about their internal state. This is a job hand-made for dancers. Wherever you live, I can almost guarantee that there is a roboticist struggling to make a machine execute movement that strikes human viewers as “correct,” “natural,” or “harmonious.” It’s a problem for choreographers to solve. The somatic perspective of dancers (awareness of how our bodies move and how we experience that) is also important, and I write more about this here.

Left: Amy LaViers in the Georgia Robotics and InTelligent Systems (GRITS) Lab in January 2009; credit: Amir Rahmani. Right: Amy in the RAD Lab in January 2019; credit: Roshni Kaushik.

In your experience, how would you characterize the dance world’s relationship to technology? Do you find a lot of interest or pushback?

This is a big question! One of the most inspiring places I’ve been is to Sydney Skybetter’s annual Conference for Research on Choreographic Interfaces at Brown University. Sydney and his organizing team bring together artists and technologists from industry, academia, and independent practice. This gathering is an annual reminder of the interest in new technology, the value for a different way of working, and support that provides opportunity for experimentation. Moreover, many attendees offer insightful criticism to the way that technology is made, which is crucially informed by their observation of context, including gender, race and privilege, meaning-making, and embodiment.

Conversely, how would you characterize technology’s relationship to dance? Do you find the arts are trivialized or appreciated in spheres that are more STEM oriented?

I rarely see that same, meaningful respect flow from engineering. And, often, when respect or support do manifest, it can do so in a destructive way. I’ve heard engineers who have worked with some of the dance world’s most accomplished artists describe these projects as “just for fun.” The collaboration can often be treated as lip service to something they abstractly know to be important, but they often don’t give real value to the utility of dance and the expertise of dancers. This is something I myself struggle with too! If you look at the spending pattern of my lab, many more dollars go to engineers than artists. Part of this is the nature of being in a mechanical engineering lab. But part of this is simply a reflection of the context in which we live. Our whole society places a lot of economic value on the role engineers play in developing technology, often overlooking the contribution of artists without which new devices and tools cannot thrive.

So, allow me to offer some unsolicited practical advice. Artists working with engineers can find an intimidating backdrop where “technical” skills are opaque and rarified, but they should work to assert their own value and expertise. For one obvious example, dancers need to get paid! For another, when consulting on an engineering project or paper, in many, if not all, cases, it is appropriate to be a co-author, even if the artist did not derive the equations or write the code (moreover, it may be that the artist cannot even understand the code or the equations… so what! As one of my longest collaborators and teachers, Cat Maguire, would say: This is just one way of knowing!) because their ideas infuse this work with a critical piece of value and utility: connection to human experience, choices of motion in time and space, and nuanced voices on how context may affect a given experiment – to name a few examples.

What’s your next project/focus?

I’m continuing from right where I started: trying to understand, generate, and identify patterns in the motion of bodies. My student Roshni Kaushik is studying how remarkably simple artificial systems do a good job of imitating human movement according to human viewers. She brings her own expertise and training in classical Indian dance, which is a wonderful contrast to my own expertise that is allowing us to explore style, culture, and internal conceptions of movement design. I am also excited to be welcoming Kate Ladenheim as my lab’s next artist-in-residence this summer. These projects highlight the intertwined roles that generating robotic motion and understanding human perception play in my group’s work.

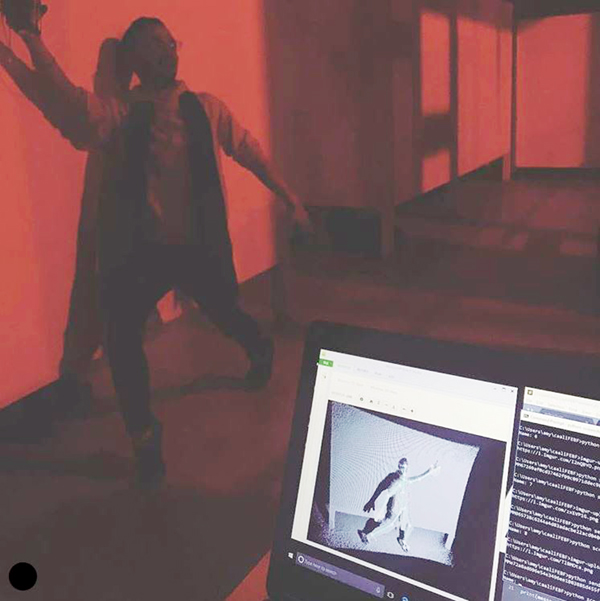

Former RAD Lab student Ishaan Pakrasi at the Hairpin Arts Center in Chicago, IL in February 2019 working on startup company caali (www.caali.xyz); credit: Amy LaViers.

~~

To learn more, visit radlab.mechse.illinois.edu.