The Credibility and Accessibility of Professional Dance

LIZ DURAN BOUBION is the artistic director of Piñata Dance Collective and co-director of ¡FLACC! Festival of Latin American Contemporary Choreographers. Here, she reflects on the dance ecosystem and its multiple biases when it comes to professional dance. Her responses are part of a larger series dissecting what it means to be a professional dancer. To read other perspectives on the topic, click here.

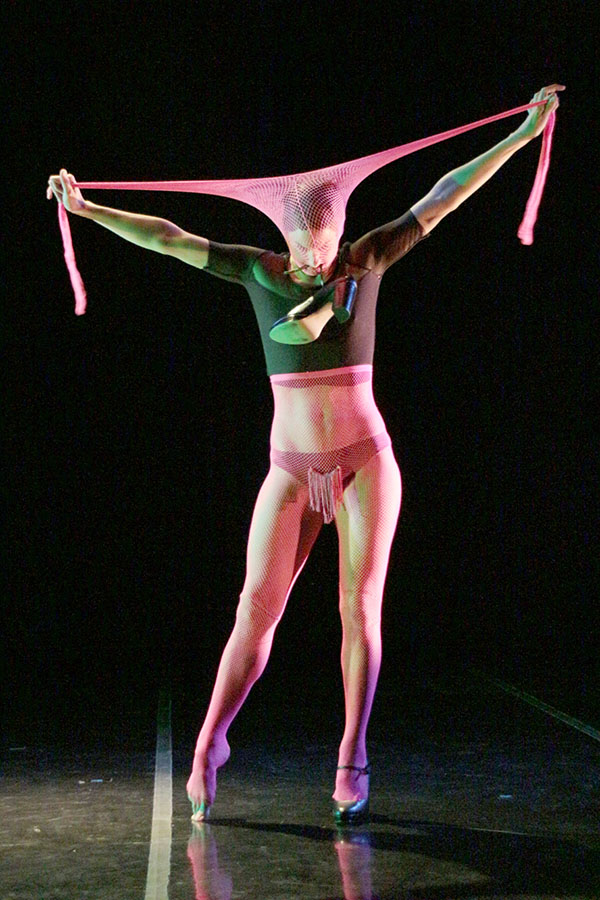

Photo by Su Pang

~~

What does your current regular dance practice look like?

I consider myself an experimental and interdisciplinary dance artist with a foundation in contemporary modern-release technique. I support this foundation with ballet, contact improvisation, somatic methodologies, Pilates, yoga and occasional cross-genre practices such as writing, singing, musical engineering or costume design. Recently, I started learning aerial bungee as part of a human-piñata installation I am working on. As a second-generation Chicana, queer and female choreographer raising my son in the Bay Area, I am interested in how multiple layers of identity reveal themselves through the body and can be supported within the language of dance theater.

I’m a dancer in my 40s and, while I would love to be in the studio every day, now that I am a presenter of the Festival of Latin American Contemporary Choreographers (FLACC) heading into its 5th year, much of my work is in the business of art: writing grants, developing alliances with local and international arts organizations, having production meetings, tackling administrative tasks, budgeting, publicity, etc. I am also a dance educator teaching creative movement, beginning ballet and yoga to children, contact improvisation and modern dance to adults, leading on-going motivational movement classes to seniors with memory loss, and I work as a Registered Somatic Movement Therapist (RSMT) based in the Tamalpa Life-Art® Process (TLAP) founded by Anna Halprin and her daughter Daria Halprin. TLAP is a movement-based expressive arts therapy model that has been instrumental in my healing process and in providing resources for my pedagogy and choreography whenever possible.

Would you call yourself a professional dancer?

Only when I spent a year dancing in Europe did I realize I was a professional dancer. After I graduated from the dance department at CSU Long Beach at age 21, I didn’t see myself as a professional because I only got paid a couple times for performing and I never felt I was dancing enough. While working three part-time jobs, I kept taking class and doing small projects, but I had some personal life challenges that took my dance path off the performance track and into the realm of dance therapy and somatic healing. Four years later, at 26, I sold my car and traveled to Europe to dance professionally (for pay) for a year in Germany. I showed a solo at a dance festival in Wurtzburg, I was hired as a dancer for the Frankfurt Opera, and I danced in several project-based companies while I was there. I was always paid for performing in Germany and was told that I was a professional dancer several times. It was a stark contrast to dance in a country where being an artist actually placed me somewhere in society, with a certain amount of status and privilege. Even though I was barely making ends meet in Germany, being a dancer was perceived as a viable profession that made me feel valued. Dancing for free simply was not an option.

When I returned to the US, dancing for free became the norm for me again, but I knew I was a professional dancer at that point. Everything I have done since then, including solo improvisations, dancing for other choreographers, offering performance labs to target populations, creating the Piñata Dance Collective, performing my work in the US and Mexico, deepening my research in somatics, teaching, curating and presenting, have all been part of my professional career. It has grown to include working for pay and working in larger venues and universities as I evolve.

What do you believe is necessary for a dancer to call themselves professional? Is part of being a professional getting paid?

I think it is necessary to both achieve a certain level of mastery of your craft and to choose dance as a career path. Some would say, dance has to choose you; it has to be something you can’t avoid. Or something that you always follow as it unfolds in your life. Whether as a dance educator, choreographer, performer, movement therapist, writer or dance historian, these are all professional tracks. It doesn’t always mean you get paid for your work as an artist but we are constantly training, collaborating and developing as artists in the community. Everything we do as dance professionals feeds into the tapestry of experience. Writing these responses for Stance on Dance is not a paid opportunity, but it is an investment in my art as a professional. It supports what I do and supports the field at large. There is something about being socially engaged, rather than in isolation, that is included in the title.

From my experience, I think there are real financial challenges for modern, experimental, contemporary and social change dancers in that there is often a deliberate choice not to be an entertainer, dancer-for-profit, or selling the body in a certain way. I remember adopting that philosophy as an anarchist/feminist dancer, making a shift from feeling objectified and artistically restricted as a competitive dancer in high school, to being an “artist” in college. It took me many years to realize that I do value dance as a form of entertainment and that one can have monetary value as an entertainer without being reduced to a product. I wish I had not equated commercial dance with the commodification of my female form. It is still an art and can be fun, clever and shiny. So, I respect the aerial dancer working for corporate parties, for example. Or the music video dancer who can do it all. Or erotic, pole, burlesque, drag and vogue dancers. Contrary to my former beliefs, dance doesn’t always have to be a service to others, as a somatic healing art, a social experiment or a political response. It can be a job to keep a roof over your head. There is no shame in that.

The competitive nature of the audition process was also a huge deterrent in my early career philosophy, so I did very few. In contemporary dance, it is known that if you attend the classes of the choreographer, you will eventually be asked to join the company organically. In my case, it was true to a certain extent and then I became a mother, which interrupted my focus again and sent me on a much more self-created dance path which came with more financial challenges. I think I am coming to terms with being a late bloomer as a dance professional but I am glad my creativity carried me though.

Is there a certain amount of training involved in becoming a professional dancer?

Absolutely. I’m a snob in that way. Like any profession, there are long hours of developing your craft and it takes dedication, time and learning to be a dancer. Whether it is the trees, wind, YouTube, or the culture you grow up in that teaches you how and why you move, there is a relationship to the spirit of dance and to the field of dance at large, that can grow you professionally. It doesn’t matter what the dance style is; it is how it has informed your body that allows you to carry it. One can be born with a natural ability to dance but there is always a practice leading to professionalism, I believe.

According to the 2016 New England Foundation for the Arts National Dance Project’s report “Moving Dance Forward,” 80 percent of respondents said they were doing project-based work and 50 percent said they were doing solo work (there was room for crossover). Do you consider project-based and solo work to be professional?

The cost of living and the lack of funding for the arts forces many artists to work alone or work very fast with who is available for a single project. There are very few salaried positions. However, there is an enormous amount of generosity, creativity and love that allows us to make work within this inherently social art-form. From individual monetary donations, to commissioned work, to artist residencies, to self-made costumes and work exchanges, there are many forms of in-kind donations such as: donated studio space, free professional consultation, cross-promotion by fellow artists, or the many volunteers who help out during a production. All of this and more supports the professional artist where our government doesn’t or when grant funding can’t cover costs. It’s a major hustle that definitely impacts our work as artists, but we become very resourceful.

For example, in order for me to make a month-long residency in Mexico feasible in the summer of 2014, I had to sublet my apartment, have my 13 yr-old son stay with his father while I was gone, and I held a benefit showing at Shawl Anderson Dance Center where I was given free space and publicity, raising about $1,400 for travel costs and artist fees. When I arrived in Jalisco, the artist residency included an apartment and a small stipend in Chapala, but it was a little too far from Guadalajara, so I contacted my friend, Maria Di Maruka, who knew the artist Lila Dipp, who knew Ailyn Arelles and Ramón Vázquez, who produced my show at a live-work space and connected me to the dancers and musicians at the Centro Cultural de Barrio San Diego where I took classes and held auditions for the show. I was really supported from all directions without any grant funding at the time. I paid 12 artists and two tech staff small stipends and I was invited to return to teach and perform in Guadalajara the following year. I also made life-long friends.

Do you think the definition of a professional dancer is different than it was 25 or 50 years ago? If so, do you have any ideas why it might have changed?

I’m noticing the semantic difference between “professional dancer” and “dance professional.” Today, I think we could be seeing the definition of a professional dancer embracing a broader spectrum of dance styles internationally, which is more inclusive of diverse backgrounds and body types. And the dance professional can encompass numerous career tracks within the field.

Also, I believe the approach to teaching is becoming more anatomically sound and emotionally healthy, making it more sustainable for dancers physically and psychologically.

According to the NEA, there is less funding for the arts now than there was 25 years ago, so this has had an impact on the whole ecosystem of dance. And while there is now a thing called “crowfunding,” I think it is more competitive overall.

Are there instances when people apply the term “professional” to a dancer or group of dancers when you feel it shouldn’t be applied?

This is dangerous territory. I would hate to offend anyone. But it’s a dynamic conversation.

It makes me think of male athletes who become paid contemporary dancers on salary with only a year of formal dance training under their belts and little knowledge of the form. But then again, what is dance? They have essentially been training all their lives with an intense physical practice that has developed a highly intelligent body to learn steps very quickly. What is more central to that conversation is how men in this country are discouraged to dance professionally and how it creates a gender imbalance for the field overall.

I would also say it is an unfit title for someone who is making money by appropriating or plagiarizing material from cultures outside their own or from other dance professionals in the field without crediting them. There are several untrained dance entrepreneurs leading entire communities of people to free their bodies via social dance or exercise. They are making a huge impact increasing the accessibility of dance to the general public while earning a profitable living from the practice. Some of these trademarked dance forms are methods that actually can carry a lot of wisdom and change people’s lives. It only gets tricky when the wisdom is borrowed or taken from other traditions or from other dancers without any permission.

Vice versa, are there instances when people don’t apply the term “professional” to a dancer or group of dancers when you feel it should be applied?

Yes.

Erotic, burlesque, pole, vogue, drag and queer dancers etc. are professionals and can be highly skillful technically or artistically.

Cultural dance forms, ceremonial dances rooted in Indigenous traditions, or dance/movement as a therapeutic and healing modality can be professionalized, performed, taught and hold monetary value.

Dance improvisation can also be developed as a highly sophisticated skill in performance and taught in academia or elsewhere.

How might your cultural perspective – where you live, where you’re from, what form of dance you practice – influence what you think of as professional?

To elaborate on my earlier statements, the art of dance (and theater) is generally visual and centered on the body and its politics. Issues of race, class, body type, age, ability, gender, culture, geography and other influences effect the credibility and the accessibility to certain dance genres for many aspiring dancers. However, where there is creativity and commitment, anything is possible.

As mentioned above, I am a queer, female, Chicana, divorced, low-income, single mother and dancer. I was raised the youngest of seven in the suburbs of LA county with a Mexican-American father who grew up poor in a culture that believed dancing was only a hobby for Mexicans and was instead for privileged, rich, white people. There was some truth in that. My Euro/Canadian mother believed that it was too late for me to be a dancer because I didn’t have formal ballet training until I started college. There was some truth in that too… but thank goodness, they didn’t block me from taking on the challenge. If I had listened to their cultural beliefs, I would not have formed a life as a dancer, which has given me a powerful language to communicate thought, emotion, energy and metaphor. It’s a language that crosses borders and cultures connecting me to people internationally. I would not have found a personal place of belonging, a source of strength, joy, freedom, healing, knowledge and wisdom, right inside my own moving body. I would not have helped others do the same. I have developed a unique skill set that I am passionate about sharing. It has not come without enormous effort and challenge, and I am simultaneously aware of my privilege based off my skin color, body type, education and eventual formal training that I embarked on at a relatively late stage of my physical development.

Admittedly, I have not yet reached my professional goals. With a BA in Dance, an MFA in Interdisciplinary Art and a certification in the Tamalpa Life-Art Process, I still do not have job security teaching in higher education. I am living month to month in my Oakland apartment, on Medi-Cal, dancing on a precarious edge of time as a project-based choreographer, presenter and dance educator. It feels like I am still hustling, but dance is at the center of my life. Some people think this is a measure of success but I am still climbing. Thank the lord, I am still dancing in good health, which is more than many dancers at my age, and I’ve remained committed to the coalescence of technique, somatics and cultural wellness as a form of livelihood that supports who I am. My cultural background and my life experiences are all resources with which to create art and to help others learn, connect, grow and achieve. By curating, presenting and teaching, I am working to provide more accessibility to the art-form and hopefully more accessibility to funding as well.

What do you wish people wouldn’t assume about the dance profession?

That you can’t dance past 40. Or with a disability. Or with a kid.

That you have to start training when you are pre-pubescent.

That it requires classical training.

That it is only for entertainment.

That we aren’t artists.

That all male dancers are gay.

That all female dancers are straight.

That dancers are dumb.

That it is easy.

That it is only a hobby.

That we don’t need to be paid for our work.

Photo by Yvonne Portra

~~

Liz Duran Boubion, MFA, RSMT, is the artistic director of Piñata Dance Collective and co-director of ¡FLACC! Festival of Latin American Contemporary Choreographers. She has been choreographing and teaching in the San Francisco Bay Area since 2001. Her work embraces the temporal nature of the body and a shapeshifting attention on identity politics, mental health and strategic cultural curating. She teaches on-going dance classes to youth, adults and to elders with neurodegenerative diseases. Visit www.lizboubion.org and www.flaccdanza.org for more information.