Curating the Craft of Choreography

An Interview with Christy Bolingbroke

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

In 2013, with funding from the Knight Foundation, DANCEClevand began a series of stakeholder meetings in order to establish a new National Center for Choreography, to be located at the University of Akron in Ohio. Today, that center has come to fruition, and is finding its footing under the helm of artistic director Christy Bolingbroke. Christy reflects on some of the opportunities and challenges unique to her position.

Christy Bolingbroke, Photo by Neil Sapienza

~~

Why create a national center for choreography?

Choreographic residencies aren’t a new idea but, in the past, residencies have been offered through a dance company, venue, or a center that offers classes. Residencies are often offered in addition to an organization’s existing programming. At this moment, with more project-based dance artists in the field, we need centers that are focused solely on the craft of choreography.

What was the impetus behind the center?

The lore is that almost 10 years ago, Pamela Young, executive director of DANCECleveland, had an audience with the Knight Foundation. They asked her if she had any big ideas for dance. She responded that France has 19 choreographic centers, and we have only one here in the US, the Maggie Allesee National Center for Choreography in Florida. It’s time we had a second.

This sparked an ongoing conversation and ultimately a feasibility study. They did their due diligence and included so many wonderful stakeholders, including Jennifer Calienes, the founding artistic director of MANCC. She helped with the infrastructure in addition to proving there’s the capacity in terms of funding and space.

What is the significance of basing this center in Akron, OH?

The Knight brothers, who founded the Knight Foundation, grew up in Akron, so the city is one of eight across the country where the foundation is deeply invested. There’s a special love and commitment on the part of the foundation toward Akron.

When I think of Ohio as a whole, it’s worth noting how many dance companies have been based here in the past half century. DANCECleveland is the second oldest presenter in the country.

There used to be a ballet company in Akron — Ohio Ballet — founded by Heinz Poll, who was a German figure skater. He built a lot of appreciation and support for dance in and around Akron. It is largely because of his indelible mark on the city that the university expanded its arts building to include more dance studios.

Ohio Ballet is no more, but it left a vacuum of available dance space at the university. In fact, one of the seven beautiful studios on campus is dedicated specifically for the Center’s use.

Separate from dance but specific to Akron, the city has a big research and development vein. It’s known for polymer science; at one point, Akron was the world’s rubber tire capital. The National Center for Choreography taps into the innate interest in research and development that has defined Akron for a long-time.

As artistic director, what are some specific projects you are initiating through the center?

I look at my role as an opportunity to do something new. It would be very easy to repeat other residency models and just add more to the mix, but I want to find what doesn’t exist yet on the national level.

We are doing some early creation residencies starting with Tere O’ Connor this summer, and our hope is to soon offer similarly product-oriented residencies, like a technical residency, because we know that production value is something that continues to be of concern in the dance field, especially with the exploration of video and multimedia.

Work by Tere O’Connor, Photo by Paula Court

Beyond that, I’m interested in how we can amplify space and proximity for artists who want to explore an idea bigger than just their next project. For example, there’s the Dancing Laboratory, which will initially center around BODYTRAFFIC, an LA-based company that commissions two or three pieces a year. The commissioning model generally suffers, because the artist must write the grant without knowing what the work will be yet, they raise the funds, and then put all the energy and resources into a few weeks, and expect the commissioned choreographer to make an amazing work. Sometimes it is, and sometimes it isn’t; there’s no room for failure or trying new ideas. We decided we want to disrupt that system, as well as offer additional opportunities that would cultivate female choreographic talent.

So what we’re hosting are three female choreographers who will join BODYTRAFFIC in Akron over the course of two weeks in September. Each choreographer will have three days in the space just to get to know each other and the dancers. They don’t have to make a piece; they can teach each other or do improvisation or writing exercises — whatever they would normally do to build a creative practice and get to know each other. The subtext is that we hope BODYTRAFFIC will later commission at least one of these female choreographers, but it’s perfectly fine it they decide not to. The Dancing Laboratory is for creative, rigorous play, and positive failure.

Beyond dance-making, I want to support discourse. It’s great if dance is getting made, but if it’s not getting seen, talked about, and chronicled, then to what end? We know we’re losing dance writers, and a lot of traditional publications aren’t carrying dance coverage anymore. There are lots of questions about who dance writing is for: a general audience? Other dance practitioners? Academics? How is the writing distributed if not through traditional print media?

As an offshoot of Tere O’ Connor’s creative residency, we put out a call for dance writers, as Tere himself has made writing an important part of his practice. We received 60 submissions — from academics, choreographers who write, bloggers, professional writers employed at the remaining publications, and presenters. It made me realize we had struck a chord. The idea is to cultivate a dialogue with Tere in order to get a sense of where we want to go and possibly create a larger platform to create more dance writing residencies in the future.

Work by Tere O’Connor, Photo by Paula Court

That dovetails with another residency I want to offer. We also need stronger administrators to help artists distribute their work and build partnerships with presenters. One of the things we hope to explore soon is what a creative residency for a dance administrator would look like. This would be an opportunity to develop strategic plans, discuss resources, and invest in capacity around the art form.

From my own experience, the dance world is increasingly project-based and less company-based. How do you see the Center balancing the needs of project-based choreographers with the needs of company-based choreographers and directors?

In the New England Foundation for the Arts National Dance Project’s report “Moving Dance Forward,” they did a broad survey of the dance field. Out of the survey respondents, 80 percent said they were doing project-based work. Some artists might still desire and subsequently develop a fulltime dance company, but there are lots of examples of dance artists who purposefully choose to work on one project at a time.

The challenge with a choreographic center is to create structures that are adaptable for both project-based and company-based artists. The project-based artist is looking for enough time and resources to subsidize themselves and their collaborators to come together and skip the day jobs for the time being. They can have an uninterrupted period in which to be creative. Many choreographers have mentioned how difficult it is to put together a rehearsal schedule of freelance company members. There are too many moving parts; you end up with a few hours here and there. Coming together with uninterrupted time at the Center can catalyze the creative process.

For a company, especially if they have their own space, there’s a different kind of value. It’s a recognition of the quality of their work. We have a generational problem in our field: more established choreographers are competing for the same limited funds as emerging choreographers. There needs to be a balance. I’m trying to be mindful of not only supporting emerging, mid-career or established artists. I want to spread the wealth.

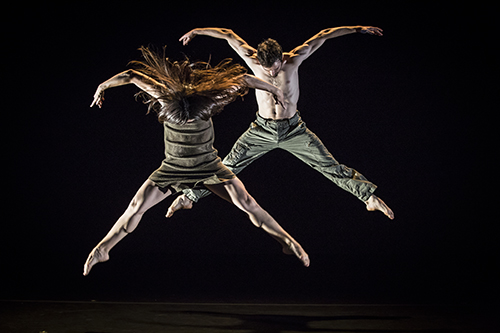

BODYTRAFFIC, Photo by Christopher Duggan

What do you perceive is your role as director, especially in terms of being a curator versus presenter?

Because presenters must sell a certain number of seats in order to present artists, they can be a bit myopic in terms of what they can and can’t offer. However, NCCAkron is not presenting performances, so my measurement of success is not based on ticket sales. I’m asking myself how I want to express a job well done. I think it arises from really listening to artists. Instead of saying, “You get a residency because your work is amazing,” residency opportunities like the Dancing Laboratory look a bit more holistically at the issues and shared interests of different artists, and what would happen if they could dialogue about those issues and interests. It’s not with the expectation they create a work together, but that they learn from one another.

I also want to be a bridge between artists and audiences, especially in terms of strengthening and advancing the art form. The challenge in any dance community is getting local audiences to follow dance beyond the companies they know. Thus, I want to offer a social experiment in the style of a book club. It’s an invitation for dance aficionados and novices alike to join us and commit to engaging with dance once a month over a ten-month period. Sometimes we’ll sit in on a rehearsal of an artist in residence at the Center, sometimes we’ll go see a local show by a regional company, sometimes we might even read about choreographic processes. The idea is to create a consistent group that sees and discusses work together in order to create a series of reference points beyond the dance artists they already like or know. We’ll see what we discover.

By what parameters will you measure your own success?

When you start something new, it’s exciting, and then you get some things going that are established, and with that comes the expectation that you will always do those things. Those expectations make you less nimble to try new things. It’s like creating and manifesting your own catch-22, and I’ve seen many dance institutions go through that. Then, when there are threats or shifts in the field, the larger institutions grapple more with those threats than newer institutions because they’ve built up infrastructure to protect that one definition of success. So one of my goals is to always stay nimble and adaptable. I don’t want to get stuck saying, “We’ve done ‘this,’ so we have to keep doing it.” We need to regularly ask, “Is ‘this’ working for us still?” Or, if it is working, find ways to get others on board so we don’t have to be the sole keepers of that success. That responsibility can crush an institution from being adaptable. Not being too normalized would be my goal.

BODYTRAFFIC, Photo by Tomasz Rossa

~~

For more information, visit www.nccakron.org.

2 Responses to “Curating the Craft of Choreography”

Thanks for reading and commenting Christy Funsch! Hope you’re well!

Thanks Emmaly,

For your always-insightful scouting and writing. Congratulations to Christy B and the new NCC Akron for the exciting new programming. Love the idea of the ten-month “dance club!”

Comments are closed.