Assessing Opportunities

An Interview with Amy Seiwert

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Amy Seiwert is the artistic director and choreographer of Imagery, a contemporary ballet company based in California’s Bay Area. In addition to a long performing career, Amy has choreographed for ballet companies across the country. She shares her ideas on why men receive more opportunities in ballet’s hierarchical world than women, and what might help women get a foothold.

“Home in 7,” Choreographed by Amy Seiwert in 2011 for Atlanta Ballet; Photo by Kim Kenney

~~

As a young dancer, what was your ultimate goal? Did it extend beyond performing?

I went to a performing arts high school and choreographed my first piece when I was 16 years old. The idea that choreography was something you had to have finished dancing in order to do was not an idea I was raised with. I was fortunate in that respect. As I pursued performing and also got more opportunities to choreograph, I knew it was something I wanted to keep doing.

Because there are so many more females than males in ballet, did it seem like your male colleagues were more encouraged to have aspirations beyond performance careers?

As a young girl training in ballet, my mother was told to take me out because my knees didn’t straighten. (They do.) This was when I was maybe 11. Had I been an 11-year-old boy, I would have been on full scholarship. The lack of empowerment girls feel in ballet at a very young age and at an age when they’re developing cannot be undercut.

On the flip side, an 11-year-old boy who decides he wants to pursue dance often has to go against family and societal pressure, which means stepping out of his comfort zone – something you surely have to do as a choreographer.

Do you believe the reasons why men routinely hold positions in power in the ballet world are coincidental or endemic?

We can continuously go into the debate of whether or not we live in a meritocracy, but I think we need advocates and opportunities for women choreographers. I danced professionally for 19 years, and in those 19 years I only did one piece on a mainstage by a woman. That’s notable. I’ve had people tell me there are as many women choreographers as men, and they might be right, but they are working on a smaller scale and not getting the opportunities to present on the mainstage as often as men. The amount of resources they have are less.

In a situation that has to remain anonymous, I know of a male ballet dancer who was threatening to leave a company, and the directors offered him the opportunity to choreograph for the next season. It was a carrot. Opportunity became a benefit given to the company’s star, who had no choreographic experience. The people in the organization who were choreographing at the time, honing their craft, were passed over.

The “why” is complex and nuanced, but at least we’re having the conversation. It would be lovely to see companies like New York City Ballet or San Francisco Ballet getting into the conversation more. In City Ballet’s defense, when they got backlash last year for talking about their risk-taking with all white male choreographers, they finally did include two female choreographers this year. And there’s a rumor San Francisco Ballet will invite someone next year of a different gender. But we’re talking so many years in between seeing a piece by a woman on that stage, and that’s ridiculous. They’re just not looking hard enough. It’s got to be a priority, or it’s never going to change.

“Carefully Assembled Normality,” Choreographed by Amy Seiwert in 2007 for Imagery; Photo by Andrea Basile

What might help more female dancers become interested in directing and choreographing?

I was involved in a situation where a company was doing a choreographic workshop to give opportunities to their dancers, and not one woman in the company signed up. I sat down with them and asked, “Ladies, what’s going on?” This was a company that had actually commissioned quite a few women. I asked why not one of the female dancers was interested. It was a little heartbreaking, because one of the woman in her mid-20s responded, “Why would anyone care what I have to say?” I told her, “What you have to say is important, and only you can say it.” But this speaks to a culture where women experience a lack of empowerment in general.

Potentially one of the reasons you hear this conversation in ballet versus modern dance is because modern dancers tend to go to college more often, and take choreography courses. There’s an intellectual rigor that’s applied to the creative process that is lacking in classical ballet dancers’ training. It will be interesting to see what happens because with the economic downturn of 2008, a lot of ballet dancers went to college. There weren’t many jobs. They went to Juilliard or the University of Utah, and are now getting hired into companies. They are used to making creative choices and taking creative chances. I’m interested to see how that changes the field.

When I was dancing, a ballet dancer was supposed to be an empty vessel. We were supposed to do whatever the person in the front of the room said. In this post-Forsythe era, dancers are now commonly asked to improvise and make creative choices to manipulate material. This practice is much more common than it was even 10 years ago. Training young dancers on a pre-professional track to be comfortable improvising is going to help them further their careers as performing artists, as well as make them comfortable with their own creative voices. Hopefully that equals more women stepping up to the table.

Talent in ballet has long been assessed through a male lens. How might female choreographers bring a different lens?

I develop a lot of partnering in my choreography. However, I am 5 ft. 2 in. and can’t actually lift anyone. When I go to create, I get in there and do all the partnering with the guy. They have to listen both with their ears and kinetically to what I’m doing. It’s funny though, because often they will start to take over, and I have to say, “Hey, let me lead.” If you think of it in terms of male-female partnering where oftentimes the man is just manipulating the woman, my approach comes from a place that’s more balanced. Even if it looks like traditional partnering, in my choreography the woman might be initiating all the movement because it came from me. It changes things visually as well as changes the energy in the room.

“It’s Not a Cry,” Choreographed by Amy Seiwert in 2009 for Sacramento Ballet; Photo by Scot Goodman

Do you prefer to be recognized as just a choreographer, or specifically as a female choreographer? Is the distinction important to you?

It’s frustrating because the conversation has been going on for so long. I don’t want anyone to view my work as “female.” But with orchestras, for instance, when orchestras started doing “blind” auditions where the player sat behind a screen, the number of women and people of color being hired by those organizations went up. To me, it would be interesting to assess four pieces of choreography side by side, two by men and two by women, but the viewer doesn’t know who made what. Would the viewer be able to tell who made which piece? This is an interesting question to me: Is my work essentially different because I am a woman? I don’t know.

Often in reaction to the lack of commissions for female choreographers, there are festivals and programs that specifically feature women. Do these ultimately serve women or separate them?

I think we need the conversation. In 2012, I was part of an evening of women choreographers for my company, and we had an interview with Allan Ulrich, the head dance critic for the San Francisco Chronicle. When I said there was a lack of women in leadership positions in ballet, he basically didn’t agree and asked me to make my case. Two things I said gave him pause. First, there’s the fact that in 19 years, I only danced one piece by a woman on a mainstage. Second, my assistant at the time, Joseph Copley, researched stats, and looked up how many companies with budgets over $5 million were commissioning ballets by women. Out of 280 ballets, only 25 were by women.

Do I wish people would just commission women? Yes. Does it need to be in these women-only, “She Says” forums? No, but it’s a marketing angle, so I understand why organizations do it.

Any other thoughts?

Recently, the New York Times ran a piece called “Where Are All the Women Choreographers?” There is something disheartening about these types of articles, because I think, “Well, I’m right here.” There are a ton of women who would love to be choreographing and directing, but are not getting the opportunities. We keep creating when and where we can. Everyone’s goal is just to make their art.

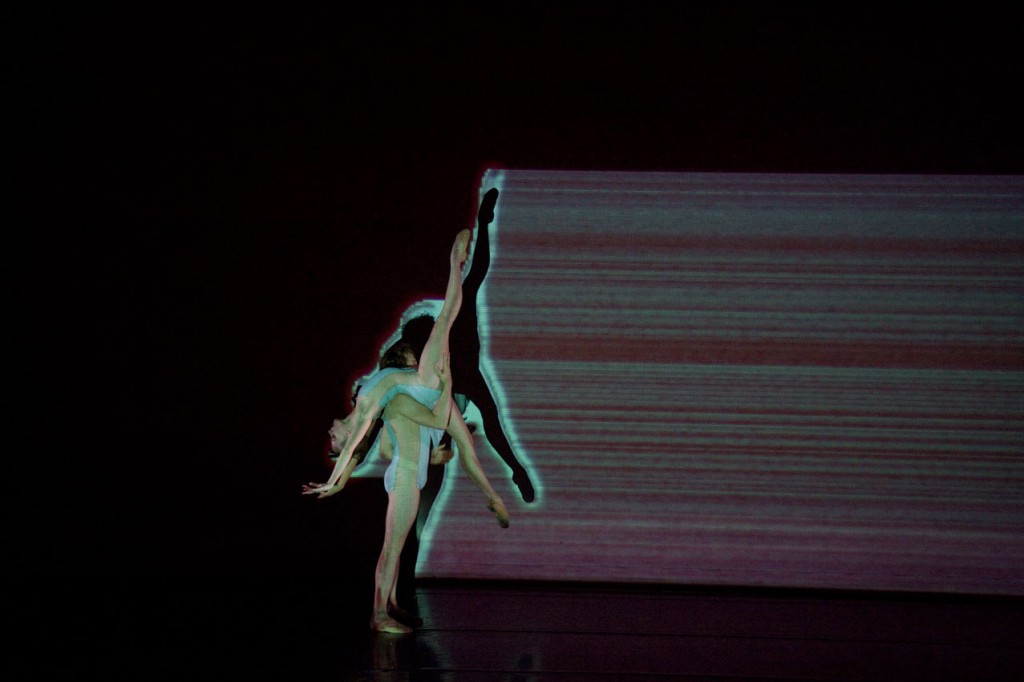

“White Noise,” Choreographed by Amy Seiwert in 2010 for Imagery; Photo by Scot Goodman

~~

Amy Seiwert enjoyed a 19-year performing career with the Smuin, LA Chamber and Sacramento Ballets. As a dancer with Smuin Ballet, she became involved with the “Protégé Program,” where her choreography was mentored by the late Michael Smuin. She became Smuin’s choreographer in residence upon her retirement from dancing in 2008. Named one of “25 to Watch” by Dance Magazine, her first full evening of choreography was named one of the “Top 10” dance events of 2007 by the SF Chronicle. She is honored to have been an artist in residence at ODC Theater from 2013-15, and to have works in the repertoire of Ballet Austin, Ballet Met, Smuin, Washington, Atlanta, Oakland, Sacramento, Colorado, Louisville, Cincinnati, Carolina, Oklahoma City, Dayton, Milwaukee and American Repertory Ballets as well as AXIS Dance and Robert Moses KIN. She is also the artistic director of her company, Imagery.