The U.S. Department of Arts and Culture: “Why Don’t We Have One?”

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

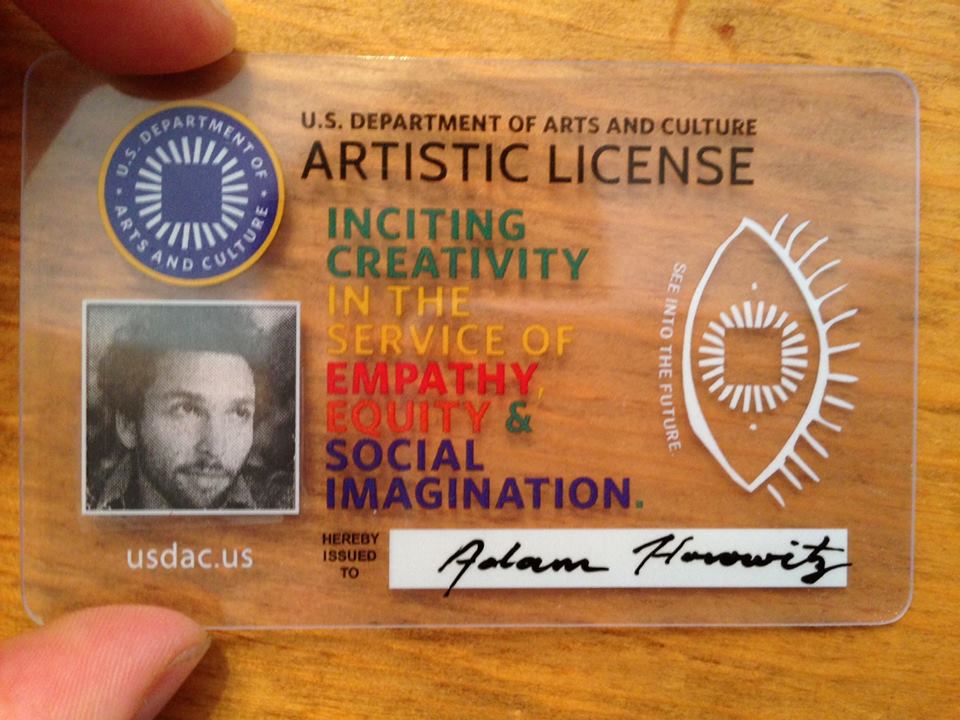

Adam Horowitz’ easy-going personality belies the scope of his work. The original dreamer and schemer behind the United States Department of Arts and Culture, he’s adept at talking about his work, but not overly eager to self-promote. However, when pressed, he does have some pretty great things to say.

~~

What was the seed of the United States Department of Arts and Culture?

My favorite thing in the world is being with other people in some kind of creative setting, making something greater than the sum of our parts. That is what I did a lot of through theater. It was the usual… musical theater, plays, this and that. But then I had the opportunity to have some out-of-the-box experiences. I ended up living in Poland one summer doing Grotowski training and rigorous physical theater. From there I landed in Peru, working with an ensemble that creates theater based on the stories of the people. It was politically engaged work that was pretty powerful to see. That led me to Denmark and Odin Theatre – they create sites of cultural barter, the idea being we all have culture. We created our own theater pieces and set up sites of exchange. These experiences got me deeply interested in how to cultivate containers for creative exchange.

Then I was living in Columbia on a Fulbright grant working with the Ministry of Culture. They had cultural centers all over the country, and I thought, “A robust and progressive cultural government agency… why don’t we have one?”

I printed out hundreds of posters for a thing called the United States Department of Arts and Culture. I made up the name. I put it into Google and nothing came up. The idea lingered; I couldn’t drop the string of words. There was no imagination for this entity.

Two years passed. I worked with different nonprofits and social enterprise organizations. I worked with a group called Ashoka, which is all about ‘scaling up solutions to the world’s most intractable problems.’ I said, “Yeah the arts!” And they said, “Mmm we don’t get it.” I said,”Aaaaah! That’s a problem!” Even in progressive organizations, I found that there was a lack of understanding of the value of the arts in bridging communities, cultivating empathy, and creating ways of thinking that allow us to imagine and create alternatives. It wasn’t on their radar; it’s not on most people’s radar.

The question became, given all the amazing practitioners, programs and projects I knew of, how might we begin to connect and amplify this whole field of work? How might we take this string of words – The U.S. Department of Arts and Culture – and begin to articulate the values we wish such a department had and perform it ourselves? We launched in October 2013, and started doing public programming two years ago. Since then, we’ve had 10,000+ participants in 40 states.

What are some personal highlights you’ve experienced doing this work?

I love seeing it come to life. I love hearing people’s dreams about what this is and could be. I love hearing why this resonates with people and why it’s filling a need.

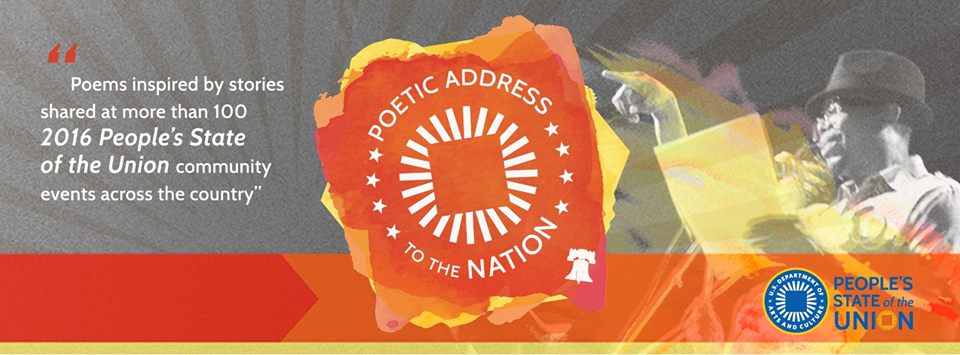

One particular moment when I said, “Yes, this is working,” was last year when we did the Poetic Address to the Nation. That’s the culmination of the People’s State of the Union. There were story circles in 150 places. They were uploaded online, and then poets turned it into the Poetic Address. The experience was so energizing. It felt like we truly accomplished a quixotic and grand idea of weaving together the voices of hundreds across the nation into a poetic expression that captured a pulse.

What are some of the challenges you face?

There are so many. There’s no blueprint for what we’re trying to do. There are many inspirations and influences, but this feels new, figuring out how to connect the technology with the values and practitioners.

A challenge, but one I feel we’re succeeding at, is how do we put out creative invitations that anyone can respond to in their own way, but have them collectively make sense as a gesture?

Then there’s the life/work balance. In startup mode, there are no bounds to the amount of work. I am not the only one of my colleagues who have dedicated so much time. At a certain point it’s not healthy. We’re starting to get to the balance, which has to do with resources to support the work. That’s an obvious challenge.

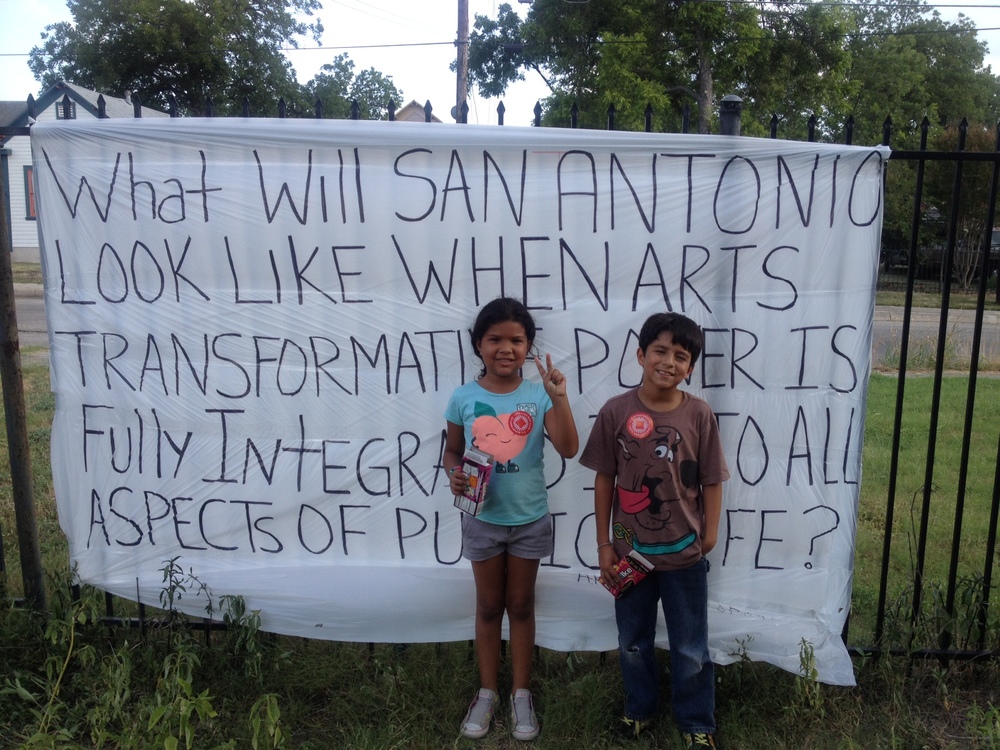

One of the broadest challenges is just making the issue matter. We have to frame the public interest in arts and culture as an issue people can get behind. Every neighborhood is teeming with creative folks and talent, so what kind of investment and infrastructure should we be doing at the city, state or federal level?

What does success look like in this endeavor, especially since the scope is endless?

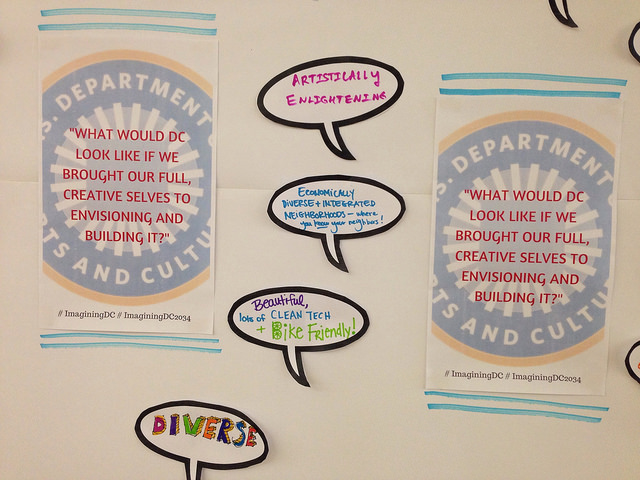

When we first started, we wrote a press release from a conference that takes place in 2034 where we announce we’re disbanding the USDAC because we’re now obsolete. We have big dreams, from artists regularly embedded in hospitals and public institutions to arts bodegas on every other city block. It’s not our work to create all that, but we’re helping to build the momentum and frame the possibility.

There’s a lot of success we cannot define centrally that happens on the local level. We can’t anticipate where all the local branches will go, but success has to do with shifting the conversation so that this work is not seen as a frill, but is truly a public good invested in at all levels.

What difference do you perceive USDAC has made?

The best answers to that question come not from my mouth but from the people who have taken part. We have quotes from our Cultural Agents who say they felt alone doing their work, and now they feel like they are part of a national network, which gives them a platform to take their local organizing to the next level.

I’ve seen a certain infectiousness of ideas. In some of the places we’ve been active, other local organizations start doing “imaginings.” They’re taking the values and spirit of social imagination and doing it outside our programmatic bounds.

We’re honestly at the very beginning.

I find dance is often underrepresented in the cultural milieu. From your perspective, how does dance exist in this rhizomatous imagining?

In terms of people in the network, dance is represented, though we’ve hardly done any medium-specific action with the exception of the Poetic Address. We’re still trying to figure out what kinds of invitations can engage. It’s in our longer term goals to create investment in cultural spaces and dedicated community cultural centers where an array of dance traditions can exist.

Our focus is largely on the participatory, and in this respect I think people are more accustomed to jumping into a visual or musical context. Bringing your whole body in is the next step, and it’s perceived as difficult for many people. It’s so critical though. I think that’s part of a culture shift at large, is re-embodying ourselves and creating spaces where our whole selves are welcome, and that includes our bodies.

Art is centralized in urban environments; smaller communities often have smaller economies, and thus less art. What is USDAC’s stance in terms of accessing smaller communities?

This is a super important question for us, and we’re trying to very intentionally not be an urban centric organization. That’s what’s so fun about these national actions we do; the dot on the map of Des Moines, Iowa equals the dot of Ribera, New Mexico equals the dot of New York City.

Story Circle in Detroit; Photo by Erin Shawgo

We’re learning a lot in terms of how to use technology. That’s been essential for everything we’ve done, including our reach into more rural communities. I’m acutely aware of the barriers to participation that happen when you have to be on a certain internet platform and download a file in order to take part. The internet can enable increased access and participation, but it’s not equally accessible to all.

We don’t have the bandwidth to really engage with tons of people who want to be doing cultural planning in their small towns or big cities, but that happens with our Cultural Agents. They host imaginings in their communities and then figure out how to use local cultural resources.

How does elitism in the arts sit beside this much more accessible vision?

I think of it as an ecosystem in which all parts play a critical role to the health of the system. Michael Rohd, a civic engagement theater practitioner, talks about a spectrum in which there are three parts: studio practice, social practice and civic practice. Studio practice is training in order to develop your art to share. Social practice is saying, “I’m an artist and I have an idea that involves a wider community.” Civic practice is, “I have a set of tools I want to put at the disposal of the community, but they dictate the needs.” All of those are essential. At USDAC, we’re not trying to say what kind of art is valid, but we are shifting the focus toward one side of the spectrum. There are many institutions and networks dedicated to the studio side of the spectrum, and fewer on the social and civic side. Meanwhile, our social crises only grow more urgent, and I do believe artists have a role to play.

~~

Adam Horowitz has worked with numerous organizations at the intersection of arts, education and social change, including the Santa Fe International Folk Art Market, Ashoka, Bowery Arts + Science and The Future Project. He has worked with ensembles in Europe and in South America, presenting original work in forests, churches, public plazas and living rooms, as well as traditional theaters. He is an artist-in-residence at the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics at NYU and the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. Adam holds a BA from Yale University and was a Fulbright Scholar in Colombia, where he wrote about performance and politics for Theater Magazine, devised original theater pieces with teens, and printed out hundreds of posters for an imagined entity known as the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture…