Stand Up for Racial Equity

BY CHERIE HILL

Note: This essay was first published in Stance on Dance’s spring/summer 2022 print issue. To learn more, visit stanceondance.com/print-publication.

When I think about activism and when I became committed to advocacy and social justice, I think back to my elementary school years. The first large-scale injustice I experienced was the 1992 Rodney King beating and riots. I can still visualize the fuzzy tape and King down on the ground surrounded by officers. I can sense the fear and confusion deep in my gut. My family lived in Los Angeles County at the time, and my mom and I drove to Compton about every two weeks to get our hair done. A couple of days after the riots, we visited our hairstylist, and I saw the aftermath of a communities’ rage up close. Burned objects and trash lay on sidewalks; nervousness, anger, hesitancy, unknowingness, and damage permeated. So this is what injustice is for Black people, I thought. I was 12 years old.

As I came of age and became more serious about dance as an artist and educator, I found myself attracted to arts and social justice. I discovered my primary theoretical lens, Black Feminist Standpoint theory, in graduate school. Developed by sociologist Patricia Hill Collins, this theory emphasizes the perspective of African American women. I could make dance pieces that focused on the Black female experience through this framework, including my own experiences. I also grew in understanding the implications of race, gender, and class through my minor in African American Studies and graduate certificate in Women and Gender Studies. As a result, creating art that reflected social change became essential and inspiring.

In Boulder, CO, I participated in my first equity training. I had signed up to volunteer for a domestic violence shelter, and volunteers were required to participate in three weekends of anti-racism and discrimination training. It was intense. The workshops laid out stereotypes and biases primarily based on race and gender through interactive seminars, dialogues, videos, and reflection circles. I’ll never forget how one of the organization’s directors spoke about racism slowly killing her. With passion, she shared how her interactions with people who challenge her, discriminate against her, and maltreat her due to being a woman of color cause severe stress. Stress leads to health problems and unhappiness, leading to a shorter life span. Prior, I had never viewed racism this way. Racism as a stress factor made a lot of sense. My upbringing, and experiences like these, helped convince and prepare me to be an equity advocate.

Photo courtesy of Cherie Hill

I have discovered that advocating for race and equity can feel good and not so good. Sometimes when I call out wrongful policies or inequitable decisions, I do not think twice about it. I know my push for equity will positively impact. Other times, I feel nervous and worry about what people think. I sense impatience from some of the people in the room. If you are a Black person or POC, this may resonate.

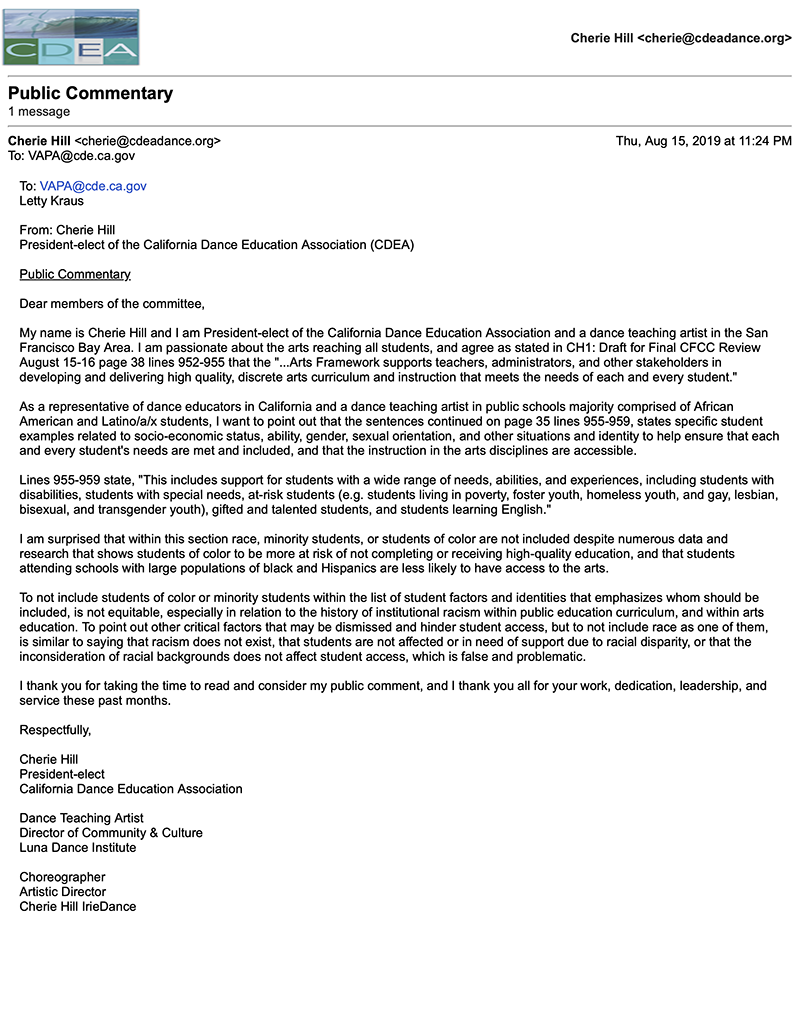

I recall my first year on the California Dance Education Association (CDEA) board, which was my first time being a “president.” As president-elect, I helped represent our membership by visiting the state capitol to observe and comment on the 2020 California Arts Standards Framework draft document. The framework is a guide to support public school educators using the PreK-12 arts standards.

As I sat in the room (public visitors had to pre-register and remain quiet during the committee proceedings), I felt pings of intimidation; it was my first time in the California Department of Education building. However, after a few hours of listening to the framework committee discuss revisions, my ears perked up when I heard them review a section in chapter 12 that cites specific identities and populations of students. The section reads:

The Arts Framework supports teachers, administrators, and other educators and supporters of arts education in developing and delivering high-quality, discrete arts curriculum and instruction that meets every student’s needs. This includes support for students with a wide range of needs, abilities, and experiences, including students who are English learners; at-promise students… lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning (LGBTQ+) students; advanced learners; and students with visible and nonvisible disabilities (California Department of Education, n.d.37).

I was happy that students needing more support were explicitly stated, but I wondered why racial and ethnic minority students were not included. Numerous education studies have found that Black and Hispanic students are the least likely to have access to the arts. In addition, due to systematic racism, Black students face more challenges and barriers to receiving a high-quality education. I felt that these and more factors qualified minority students to be included in this clause.

Later that night, I prepared my public comment to be read before the framework committee. I felt nervous. The next day as I read my letter, my hands shook, my heart raced, and my voice cracked. I did not want to be “that person” bringing up race, but I was.

Upon completing my full public comment, I exhaled a sigh of relief. A few people thanked me, some avoided me, but I did what I felt I needed to do on behalf of my students. I was proud of myself, as nerve-wracking as it was. Gratefully, my work in racial equity does not always feel so precarious.

A copy of Cherie Hill’s public comment submitted to the California Department of Education’s 2020 California Arts Framework Committee.

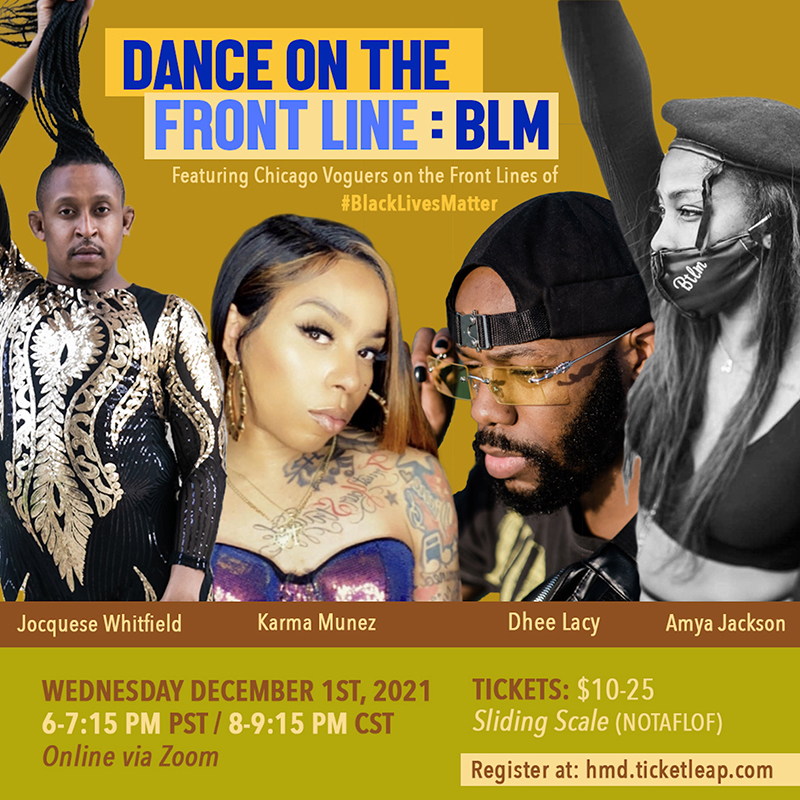

In 2021, HMD/The Bridge Project presented an Anti-racism in Dance series, and I curated the event Dance On the Front Line: Black Lives Matter, inspired by the 2020 racial uprisings. The event provided up close and personal interviews about the experience and life of artists who danced and protested for Black Lives. Finding speakers took many months because many of the dancers who danced on the front line of the protests’ names and contact information were not documented. I searched through articles and social media videos to find dance activists and asked fellow dance colleagues for any connections. When I found someone’s contact information, it was usually their social media handle. I would send them a direct message, hoping they would see it and respond. Thankfully, I was able to get in touch with three voguers from Chicago who protested in support of Black and Black Trans Lives Matter.

During the online event, the artists shared video footage of their protests and details about what prompted them to dance in front of rows of police cars. We learned more about how these protests and videos viewed all over the world impacted their lives. They also shared insight into the history and style of voguing, and the people they are influenced by. The conversation turned out to be refreshing and authentic. When asked why I would want to curate an event like this and why in 2021, I responded:

“The public murder of George Floyd galvanized an international movement for Black Lives Matter. Although it took place over a year ago, the effects of last summer’s uprisings ripple throughout our arts ecosystem. Prompted by the rawness and power of folks taking their demands to the street, more and more organizations are beginning to shift toward greater equity. But the work is far from done” (Cristi, AA. 1).

The pandemic and racial uprisings led to essential conversations around race, and leaders uncommitted to equity were called out with some stepping down. Arts administrators witnessed some dance organizations implement internal policy change and exhibit greater awareness around race and privilege, but creating equity for Black lives and those on the margins is still a huge aspiration.

HMD/The Bridge Project’s Dance On the Front Line: Black Lives Matter, flyer designed by Karla Quintero

My commitment to advocacy and equity would not feel complete without applying it to my artistry. During the pandemic, I continued my research in eco-feminism and Black Feminist Standpoint theory, and I came to know the work of Kenyan environmental activist Wangari Maathai. Wangari’s life story helped me better understand the intersectionality of colonization, oppression, and the environment. Taking over people means separating them from each other, disconnecting them from their land and resources, and eradicating them of their culture. Maathai once said, “All people have their own culture, but when you remove that culture from them, then you kill them in a way. They may be alive physically, but you kill them” (Merton, Lisa, and Alan Dater).

To share Wangari’s incredible work through my art, I directed the project “Earth Echoes,” which included the new dance film Seeds of Hope and an online panel event featuring majority-Black women working in the arts and environment.

In my creative process for Seeds of Hope, I made dance phrases connected to the knowledge and history that Wangari shares in her documentary. For example, Wangari talks about deforestation and how it is a chain that disempowers and harms people. First, cutting trees leads to a lack of water, leading to a lack of firewood, the inability to traditionally cook, and the forced consumption of highly processed food, ending in sickness, disease, and death. In response, I choreographed a dance phrase that traveled linearly through space, emphasizing this invisible chain with my body.

Another dance section is a structured improvisation I call the Planting Trees Score. The dancers spread the soil, throw the seeds, gather and pack the dirt, carry the sprout, and place it inside the earth. We experimented with performing this score multiple ways, using different body parts, counts, duration sets, and sequence orders.

A photo still from the film Seeds of Hope, choreographed by Cherie Hill and performed by Hill and Lashon Daley, filmed and edited by Alexa Burrell

Standing up for equity and inclusion is critical. As dance artists or administrators, there are numerous ways we can advocate for social justice. I am grateful for the opportunity to support racial equity in my roles as a dancer, and I encourage those reading this to find the moments where you feel inspired to do the same. Equity is not a choice if we want our field to be inclusive and vibrant; it is necessary to benefit us all.

~~

References:

California Department of Education. “California Arts Education Framework – Visual & Performing Arts (CA Dept of Education).” California Department of Education, https://www.cde.ca.gov/ci/vp/cf/. Accessed 25 March 2022.

California Department of Education. “California Arts Education Framework – Visual & Performing Arts (CA Dept of Education), Chapter 1 page 37.” California Department of Education, https://www.cde.ca.gov/ci/vp/cf/. Accessed 25 March 2022.

Cristi, AA. “HMD’s The Bridge Project Presents A Conversation with Voguers Around Dance and Social Justice.” Broadway World, 27 October 2021, https://www.broadwayworld.com/san-francisco/article/HMDs-The-Bridge-Project-Presents-A-Conversation-with-Voguers-Around-Dance-and-Social-Justice-20211027. Accessed 25 March 2022.

Merton, Lisa, and Alan Dater, directors. Taking Root: The Vision of Wangari Maathai. Marlboro Production, 2008.

~~

To learn more about Cherie’s work, visit www.iriedance.com.

Cherie Hill is a dance educator and choreographer whose art explores human expression in collaboration with nature, music, and visual imagery. She has published research in Gender Forum, The Sacred Dance Journal, Dance Education in Practice, andIn Dance, and has presented at multiple conferences including the International Conference on Arts and Humanities and the Black Dance Conference. An advocate for equity, she has presented work on embedding dance and equity into practice at NDEO, National Guild for Community Arts Education, and Alameda County Office of Education conferences. Cherie has held artist residencies with Milk Bar, the David Brower Center, and CounterPulse’s Performing Diaspora Residency Program.

This essay was first printed in Stance on Dance’s spring/summer 2022 print issue. To learn more, visit stanceondance.com/print-publication.