The Class My Mother Built

BY LUCY GENT FOMA

Despite my mother insisting I finally go to bed, I peeked my head out of my bedroom door. It was almost one in the morning, but nobody from our dinner party had gone home yet. They were still telling stories about growing up in Africa or about the wild camp where they had just taught. Our guests were all Africans: dancers, drummers and performers who my parents would invite to stay with us and guest teach my parents’ dance class. Their stories lured me out of bed. My mother threw me a scolding look and then opened her arms for me to come sit on her lap while the tales spun to their raucous conclusion.

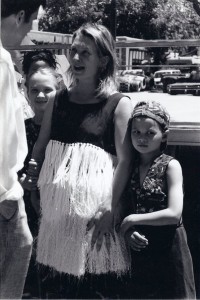

My earliest memory of dancing was in a performance with my parents around age five. An ensemble of women adorned in African print skirts and cowry-shell embroidered black sports bras made up the chorus. I had a small solo in my own miniature cowry-top; I knew how to do one of the fancy steps even some adults had trouble doing.

My earliest memory of dancing was in a performance with my parents around age five. An ensemble of women adorned in African print skirts and cowry-shell embroidered black sports bras made up the chorus. I had a small solo in my own miniature cowry-top; I knew how to do one of the fancy steps even some adults had trouble doing.

African and Haitian dance have always been part of my life. My parents started teaching in Santa Fe before I was born. I went to my first Haitian dance camp and ceremony at age 18 months. As my mother tells it, “We went to a ceremony in New York City, with mostly Haitian people, and it was the children’s part of the ceremony. You ended by rolling and writhing on the floor — something you had never seen anyone do, and you were the only child who danced. All the Haitian mamas and papas were laughing.”

As kids, my younger brother and I rarely took my parents’ class, which has happened every Monday, Wednesday and Saturday for the past thirty years. Instead, we stayed with a baby-sitter just outside of class, either playing in the dressing room or getting to watch local channel 2, the only TV allowed. I took it for granted — an institution that would never change. It wasn’t until I went away to college when I really started to understand how unique my mother’s dance class is.

It’s a running joke in our family; my mom routinely tries to describe someone by saying, “He used to come to dance class.” We laugh because nearly everyone I’ve ever met “used to come to dance class.” Santa Feans and tourists alike know there’s an awesome African and Haitian dance class on Saturday mornings in the Railyard. It would be hard to miss because the drumming pulls at everyone within a mile radius. Inside of the sun-filled studio my father built, seventy to ninety people regularly gather to dance and connect with each other.

More than just missing the chance to dance while I was on the East Coast, I missed the space my mom holds. Dance class is her life, a full-time job she has trained for since her own childhood attending the School of American Ballet in New York City. It’s all she’s ever wanted to do and something in which she invests many hours of thought, preparation and care every week.

More than just missing the chance to dance while I was on the East Coast, I missed the space my mom holds. Dance class is her life, a full-time job she has trained for since her own childhood attending the School of American Ballet in New York City. It’s all she’s ever wanted to do and something in which she invests many hours of thought, preparation and care every week.

An hour and a half before class starts, she’s still planning what she’ll teach, rehearsing steps and choreography on her wooden kitchen floor. Then she begins working herself into a higher energy state by drinking coffee, showering and bopping around to Michael Franti blaring on her radio. When she gets to the studio, she clears the space with incense as people trickle in. She asks everyone to clear their sight by passing water across their foreheads from a bowl she provides. “Leave all the outside stuff outside, we’re here to dance,” she explains, and it works.

By the end of class, I always feel lighter. Sometimes I can’t even tell you which dances we did by the next day, but I can always recall the smiles and hugs I shared, who gave news about their child’s success at school, or whose mother is having a surgery and needs our thoughts. The majority of the people who dance with us have been part of our community for a decade or longer. They are my fellow parents of toddlers and my friends’ mothers, the people who we invite to summer parties and who bring apricot preserves to share when fall is coming to a close. To say I have affection for these people is an understatement. I treat dance class and all the individuals who make up this community with upmost care. They are the heart of our lives, and that heart would not beat without the class my mother has built.

Photo by Jennifer Esperanza

Lucy Gent Foma studied at Smith College and Cornell University, researched dance in Senegal on a Fulbright, and currently works at Bandelier National Monument as a transportation scholar. She returned to her hometown with her husband to raise their daughter and help her parents run their family business, the Railyard Performance Center. She is releasing her first book in spring 2016, Funded! Find out more at www.lucygentfoma.com.