Creative Dexterity in Higher Education

BY SHANNON OLESON

Shannon Oleson is a freelance dance artist, educator, and researcher currently based in London, UK. Below is an overview of her research on creative dexterity in higher education taken from her full thesis. This research was submitted as part of her recently finished Master of Fine Arts from Trinity Laban Conservatorie of Music and Dance.

~~

The initial idea for this research was based on my dance training in both the United States and the United Kingdom. I felt dance training in the US was more technically based, while training in the UK was based more in creative development. I wanted to understand what training was the best for becoming a professional dancer, finding the gaps in my training and then filling them in. There are far more dance program graduates than there are professional dance positions. I wanted to see what traits choreographers most value in dancers and where these same traits are taught in higher education. I wanted to quantify these traits, to help both myself and other dancers become employable.

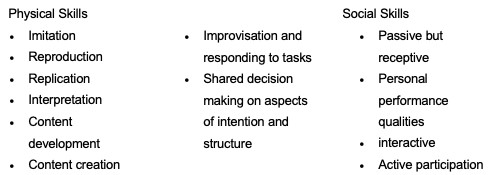

This led me to the research of Jo Butterworth’s didactic spectrum and Rowe and Zeitner-Smith’s research on creative dexterity in higher education. Rowe and Zeitner-Smith defined creative dexterity as “an ability to shift between levels of engagement with the choreographic process” (Rowe & Zeitner-Smith, 2011, p. 41). Butterworth defined these dancers’ skills as needed to successfully shift in a variety of choreographic relationships:

Because Butterworth’s didactic spectrum speaks to varying levels of engagement in the choreographic process, and Rowe and Zeitner-Smith defined creative dexterity as shifting between processes, it seemed that these traits could be used to encompass creative dexterity. I set out to see if and how these traits were developed in higher education, and where creative dexterity is embedded in higher education curriculum. Alongside interviews, I engaged in a personal investigation reflecting on the professional engagements I had throughout 2018-2020 to see where these traits of creative dexterity were in my own practice and to evaluate the different dancer-choreographer relationships I have worked in. Evaluating these relationships helped me understand the different ways to be responsive in a creative practice and guided my contribution in a variety of choreographic processes.

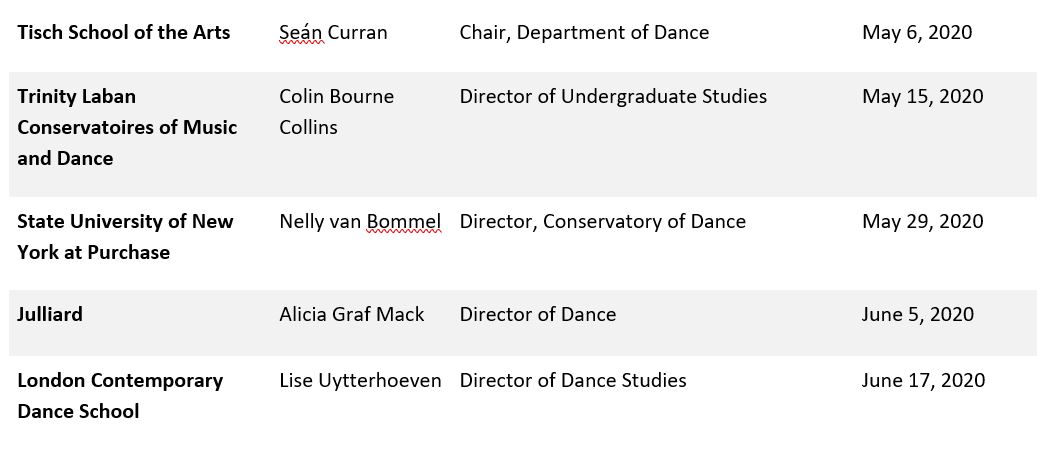

After identifying the aspects of creative dexterity, I interviewed artistic directors, directors, and department chairs at various dance institutions, asking how creative dexterity is taught in their programs. I interviewed:

All interviewees were kind and open to talking about their programs in detailed and informative ways. All interviews were no more than one hour. I conducted open-ended questions to allow the program heads to speak more freely on what they found important for their program. When interviewees went off topic, I let them continue to speak on their tangents to hear more about what they value in their curriculums. These interviews do not provide a comprehensive understanding of the programs, but are a selection of their ethos and philosophy in their departments at the time of the interviews. All interviews were recorded and transcribed so that comparisons and common themes could be analyzed, evaluated, and reflected on.

From the interviews and my personal investigation, I quickly realized that the ‘dancers skills’ traits from Butterworth’s (2004) didactic spectrum did not fully support all aspects of creative dexterity. The definition Rowe and Zeitner-Smith defined and the terms from Butterworth do not fully encompass the characteristics and ideas from my talks with these institution’s leaders. There needed to be additional qualities of creative dexterity to fully represent what the interviewees were describing. These additional qualities not only make up a great performer, but make a dancer more adaptable and able within the professional dance sector.

Interviewees spoke of the dance techniques offered in their programs. The common techniques were ballet, Cunningham, improvisation, and composition. Institutions offered different amounts of those techniques, varying from one to four years, as well as additional techniques that differ from institution to institution. The importance for dancers to be technically diverse and receptive to choreographers was widely acknowledged. For example, I personally felt the need for diverse techniques when working with the choreographer Karole Armitage. She worked with the ‘dancers as interpreter’ (Butterworth, 2004), wanting the dancers to copy her and add a bit of themselves. Then she would pick the dancer that emulated what she wanted. The rest of the dancers would work to imitate what the other dancer did.

The interviewees also spoke of wanting and encouraging students to be in creative collaboration. Institutions require collaborative projects and have collaborative processes with guest choreographers. Most institutions also encourage students to use studio space to make their own dance works on their own or with their peers. Some institutions promote collaboration across disciplines, having dancers work with musicians, designers and other production specialists. The interviewees stressed the need for collaboration in projects and in daily classes. Dancers need to be comfortable working with choreographers who want to ‘co-create’ and ‘co-own’ dance works. For example, in rehearsals for “Snow White Re: Imagined,” the dancers, including myself, worked with musicians, composers, and producers. With a variety of backgrounds, mutual understanding was difficult. Composers were constantly changing music and timing, which made it difficult for dancers to set work. Understanding others, working together, and collaborating across disciplines is imperative in the dance field, and the need to practice and collaborate at an undergraduate level helps prepare dancers for the professional world.

In previous creation processes, I’ve been asked to create content with a specific style in mind. My lack of experience creating material left me feeling inadequate compared to the other dancers. This was due to a myriad of variables, but the difficulty I had feeling safe to try new things was limiting. No interviewees spoke directly to ‘teaching’ a safe environment, but all the institutions defined a notion of absorption, willingness to learn, and the ability to process information clearly. It is possible to assume that a safe environment is needed to encourage risk-taking, collaboration, and allow new ideas to intertwine. This assumption of a safe environment in higher education is essential to the development of creatively dexterous dancers.

New ideas offered by higher education professors play a role in encouraging self-reflection in classes to help students understand what they are learning. Professors can also provide a multitude of ways to offer information so that dancers are able to process and learn in different ways. At the Hofesh Shechter Intensive, the teachers changed daily, and while all the teachers were teaching the same principles of movement, each teacher relayed the information to the dancers in a different way. Sometimes the teachers would provide specific tasks to follow, while others would give ideas and let dancers interpret them. The difference in higher education programs and professional training programs is that, in higher education, professors are expected to articulate what and how dancers are learning. Additionally, higher education programs in the US now understand the importance of creating well-rounded dance artists, rather than dancers who are solely technically diverse. This is contrary to my original hypothesis. UK programs offer as much technical training as the US, leading me to believe that the UK dancers are as technical. Intensives and professional training outside of higher education may lack development of the whole artist, leaving out conceptual frameworks and therefore leaving more of the development of creative dexterity to the dancer.

This led me to believe that creative dexterity is not necessarily something that can be specifically taught, but rather something innate which can be developed through professors and experiences. Creative dexterity is being developed in all institutions, but the institutions’ definitions of creative dexterity and Butterworth’s dancers’ skills leave gaps in the traits that define creative dexterity.

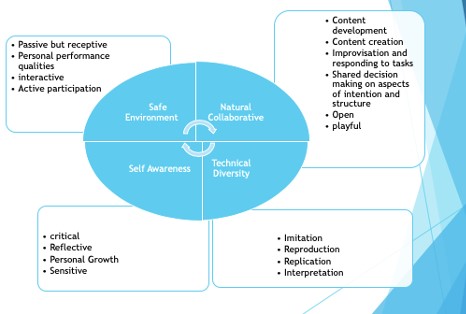

I propose that creative dexterity is a myriad of things but most specifically a mix of environment, self-awareness, technique, and creativity. Included below is a chart with my proposed amendments of creative dexterity. It includes many of Butterworth’s traits, but includes additional criteria as well. My proposed reframing creates subdivisions of creative dexterity with skills that could be developed in each subcategory. These are not the only skills that contribute to the development of the subcategories of creative dexterity, but are a mixture of Butterworth’s traits and qualities that came up in the interviews.

In this way, creative dexterity is not teachable as a whole, but many of the components can be cultivated and nurtured individually within safe learning environments. As dancers continue to learn, create, and grow in higher education, they then learn to cultivate this environment for themselves and can continue to develop creative dexterity in themselves and others in professional settings. This reframing of creative dexterity can also be used for professionals to identify strengths and weaknesses, allowing dancers to see the skills needed to become the best dance artist they can be.

Figure 3.1 A Reframing of Creative Dexterity, By Oleson, 2020

There are many unanswered ideas and thoughts that could be used for further study. My research looks at where creative dexterity is embedded in higher education learning from an overview. What could be investigated further is seeing how specific teachers support the development of creative dexterity in specific classes and through specific dancer-choreographer relationships. Much like my experience with David Waring’s class, the need to approach a class from a creative understanding rather than a verbatim imitation changed my ideas of dance and opened my mind. How and where is this evident in other classes? Would different approaches change dancers’ ability to take in information in a variety of classes? Would it change anyone’s approach or help understanding and learning?

This research on creative dexterity could be taken further to help students find programs that best suit them. It could also be continued to ask choreographers what they are looking for in terms of creative dexterity and see if my definition and framing of creative dexterity remain true or if additional criteria are needed. Hopefully, training is aligned with professional needs. This research could aid choreographers in understanding their preferred ways of working as well as guide students in their own engagement in dance. This research could be used to help choreographers identify their preferred way of working with dancers and the skills they are looking for in auditions or matching with other companies to set work so that expectations and understanding are clear.

Creative dexterity is not only a physical quality but a mental openness and curiosity that develops in creative dancers. This research could be used to support psychological studies on openness and isolating the mental aspects of creative dexterity for a broader use outside of dance.

~~