Actions and Iterations of An Indigenous Female-Led Future

BY JACQUELINE SHEA MURPHY

This past July at the New Moon Ceremony in Berkeley, California – which was called for in the “Indigenous Women of the Americas Defending Mother Earth” treaty – treaty signer Pennie Opal Plant spoke of two things needed in this time of planetary crisis. We need direct action: showing up and putting our bodies on the line to stop desecration. And we need artists and visionaries, those who envision a future beyond this destructive cycle of greed and resource extraction, to step forward and ask: What is the world we want to see?

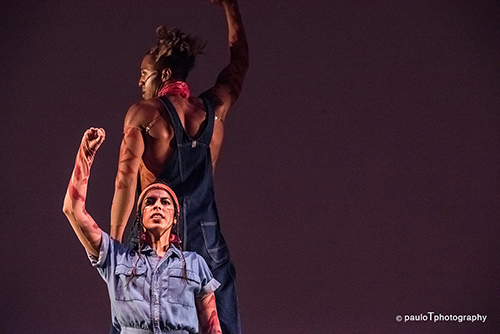

Photo by Paulo T

This was the 23rd such ceremony since the signing of the treaty on September 27, 2015. “We call upon our sisters and their allies around the world to gather together on each new moon to pray for the sacred system of life, guidance and wisdom,” the treaty reads. It calls, in other words, for the ongoing, resilient, focused dedication of Indigenous women leaders to gather in ceremony and solidarity at sites all over the world, in whatever conditions (it was blustery and cold for this July’s gathering, wind whipping off the bay), to ask for guidance and envision paths to a more balanced earth.

Plant’s voice speaking excerpts from this treaty are part of the soundscape of Dancing Earth’s latest work, which is comprised of an interrelated body of ecological dance pieces that started with the company’s “Of Bodies of Elements” in 2009 and has been manifesting anew in various forms and places over the past year.

I first saw this new work in July 2016. Entitled “SEEDS: Red Generation” at the time, it was performed at Riddu Riđđu, an Indigenous festival held annually in Olmmáivággi, Sapmi (Sami land), in northern Norway. I next saw a version called “WAAWIJEKIDEWAN/We Stand Together” at an academic dance studies conference in Pomona, California (The Society of Dance History Scholars/Congress on Research in Dance or SDHS/CORD), where I helped curate an evening of indigenous choreography. A few weeks later in San Francisco, the piece was billed as “TREATY-MAKING: We Stand Together,” as part of FLACC (Festival of Latin American Contemporary Choreographers) at Dance Mission Theater, and was soon after reprised in a different configuration as part of the D.I.R.T. festival (Dance in Revolt(ing) Times) in April 2017. Another iteration I saw came in March 2017, presented at Minneapolis/Saint Paul’s Ordway Theater as part of “Oyate Okodakiciyapi,” an Ordway community engagement series. At each site, Indigenous leaders from the region participated in the performance: two young Sami women dancers at Riddu Riđđu, Pomo Dance Captain David Smith in Pomona, and Costanoan Ohlone leader Kanyon Sayers-Rood at the San Francisco venues.

Photo by Tim Trumble

At the Ordway, the piece opened to a striking set, with Minneapolis-based Dakota elder, leader and healer Janice BadMoccasin at the center of the stage while other dancers bunched in pod-like cloths and hoop dancers flanked the stage. Striking filmed projections of the dancers on canyons and mesas in Jicarilla Apache territory filled the back screen of the theater space. The stage seethed with movement, dancers at times writhing upward towards the light, seeding space not just across the horizontal but, later, vertical in the form of stunning aerial work that extended the space skywards.

The various iterations of the piece all included excerpts from the Indigenous Women of the Americas Defending Mother Earth treaty. Some were remixed with poems recorded on site at Standing Rock, and with songs, including AudioPharmacy’s “Corporate Terrorism” and Frank Waln’s “Oil 4 Blood.” Each also included sections honoring water, through sound and dancers’ movements; labor, with dancers in blue denim work suits carrying each other; and beauty within, as the dancers emerged out of their suits as plants, intertwining.

The pieces not only reference recycling, gardening and using what you have where you land, they also enact this in their own structure, drawing from previous Dancing Earth choreographies and replanting them in new ways, thus growing appropriate to the terrain, the available dancers, the stage space, and the message that needs to be made in that moment. Like the New Moon Ceremonies, the piece is an ongoing endeavor and commitment, with regular iterations that come into form in relation to the space, who shows up, what’s needed, and what the conditions and capacities of the moment are. The piece has a template and plan, but it’s not a set work for a certain number of specifically-trained dancers with an immutable score that begins when the lights go up and ends as the curtain falls.

Photo by Jacqueline Shea Murphy

Indeed, if you hang around, where the stage begins and ends begins to feel somewhat arbitrary. In the Ordway production, dancer Lupita Salazar handed out seeds. Afterward in the lobby, I overheard Tangen speaking with someone about how in “real” life Lupita is a farmer. In Pomona, after the piece ended, the dancers left onstage laughed and cleaned, enacting the work they do to make each performance possible. The dancing is often still happening even as the “show” ends. And it will continue, both seen and unseen, on and off multiple stages and for a diversity of audiences, while it is needed.

At the talk-back after the performance at the Ordway, Rulan explained that the impetus for the piece is to envision a different world than the one we are in – and not just to envision it: to also embody it. Envisioning a better future, as Pennie Opal Plant remarked at the July New Moon Ceremony, is part of what is needed from artists and visionaries right now. Dancing Earth does this by showing us all a vision of a future (as well as present and past) in symmetrical balance. Yet as I see it, it engages the other part of what Plant said as well: It is a direct action in the here and now. The piece speaks passionately and accessibly about the “oil for blood” destruction that corporate capitalism and its extractive practices are wreaking on Indigenous communities and the planet.

All of Dancing Earth’s work engages with young Native dancers (as well as elders and dancers with a wide variety of body types and abilities). These dancers embody not just a future vision of a more balanced world, but an experience of one now. The work, in other words, is not so much an envisioned Indigenous future as it is an Indigenous inhabitation of the present (albeit alongside the destruction of extractive capitalist coloniality). And, for those of us following, we experience what a future led by a strong, tenacious, dedicated, Indigenous woman leader, actually already is.

Rulan Tangen, Photo by Ørjan Bertelsen

~~

Jacqueline Shea Murphy is an associate professor of dance at UC Riverside.