The Discussing Disability in Dance Book is Published!

By EMMALY WIEDERHOLT, in conversation with SILVA LAUKKANEN

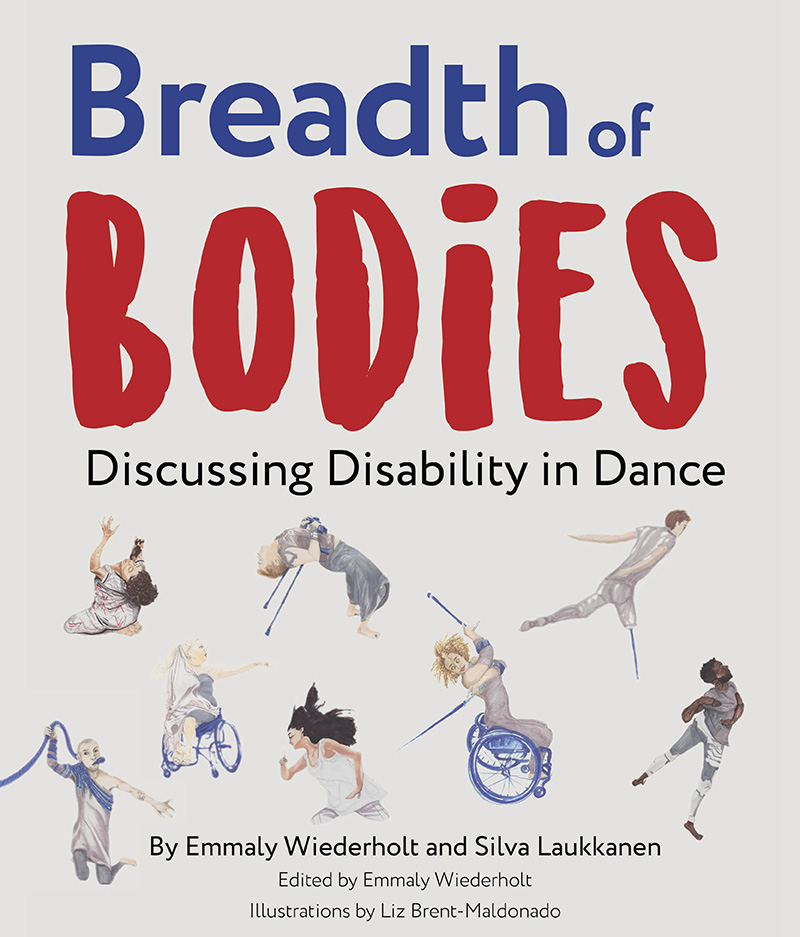

We are thrilled to announce that Breadth of Bodies: Discussing Disability in Dance is published and available for purchase! We are excited to offer the book in print as well as in ebook and audiobook format. Additionally, all 35 interviews will eventually be published on Stance on Dance where they can be accessed for free. This book has been five years in the making and we are honored to share it with our community. Below is the book’s introduction. We hope you enjoy and are motivated to make dance more accessible to those with disabilities in your own communities.

Image description: The cover of “Breadth of Bodies: Discussing Disability in Dance” in blue and red bold typeface with small illustrations of the dancers Erik Ferguson, Christelle Dreyer, Nastija Fijolič, Toby MacNutt, Alexandria Wailes, Alice Sheppard, Evan Ruggiero, and Jerron Herman (L-R). Designed by Christelle Dreyer.

~~

One in four people in the United States has a disability that impacts a major part of their life, according to a 2018 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1 There are few dance environments that mirror that statistic. And because the dance world would be stronger and richer artistically if it did, my colleague Silva Laukkanen and I have compiled these interviews that seek to document the lived experience of the dancers who are making that shift happen.

I began this project after choreographer Alice Sheppard invited me to see her touring piece DESCENT in 2017. I was unable to do so but instead suggested an interview with her for my publication Stance on Dance. I had known Alice from my experience performing with AXIS Dance Company in 2009. Alice had since become an independent dance artist, and I was intrigued to learn more about her journey creating a piece that was specifically choreographed for two women using wheelchairs.

After the interview, Alice informally shared with me her general frustration with the press. From her years of experience working in AXIS Dance Company and then as an independent dance artist, she recognized a pattern in which reviewers, dance writers, and scholars in dance and performance studies tend to focus more on disability when writing about disabled dance artists, rather than on their art. I thought this was an intriguing phenomenon to dive into.

In 2017, I published my first book, Beauty is Experience: Dancing 50 and Beyond, in which I interviewed dancers ranging in age from 50 to 95. By focusing specifically on aging in dance, I was beginning to have more awareness of access and representation. However, the book was generally inspirational. Here, Alice was proposing a different narrative: Where is the inspiration coming from – the fact that the aging (or in this case disabled) person is dancing, or because of what they artistically have to say?

My friend Silva is a passionate advocate for dancers with disabilities and has taught extensively in integrated dance. For the past few years, she has also been producing the podcast, DanceCast. My intuition in asking Silva to join me in this budding project was her considerable connections within the disability dance community. I also reached out to Liz Brent-Maldonado, a good friend and talented visual artist in San Francisco, to create original illustrations. Liz previously illustrated for Stance on Dance, and I’ve always admired her ability to blend realism and whimsy.

Our interview questions focus not only on each dancer’s history and practice, but also their experience navigating stereotypes, press, educational opportunities, language preferences, and assimilation. Because our questions demand an intimate knowledge of the dance world, the focus of our project became professional dance artists with a significant amount of experience. Though there is great work being done in educational settings for dancers with disabilities, our aim was interviewing those with substantial performance experience. Since teaching and performing are often parallel trajectories in the arts, many of our interviewees have extensive teaching experience as well, but they were selected to be interviewed because of their experience working as dance artists.

Silva and I are aware that the word “disability” does not encompass one experience, and thus tried to include dance artists with different disabilities including those who use a wheelchair, use crutches, are Deaf, are visually impaired, or have an intellectual disability. We additionally reached out to dance artists from various genres and diverse racial and gender identities.

Our selection of interviewees thus reflects larger conversations on racial and gender representation, as well as conversations about access not only in terms of ramps and interpreters, but also socio-economic and geographic access to attend dance classes and performances. There have been many intersections to keep in mind during this project. In the end, Silva and I interviewed 35 professional dancers with disabilities from 15 countries who practice a variety of dance forms and who comprise multiple identities.

This is not a “who’s who” or compilation of all the dancers with disabilities. Instead, it’s a cross-section. As our subtitle suggests, it’s meant to be a discussion of disability in dance. As we neared completion, Silva and I were fueled by the depth and variety of disability dance artistry around the world; there are infinitely more dancers than we could realistically include, and we sincerely hope someone picks up where we left off.

Finally, we want to acknowledge that Silva and I are not disabled and come from places of privilege. We are attempting to use that privilege to host a dialogue we believe should be happening in dance.

What exactly is that dialogue? If dance is art, and art is expression, and expression is predicated on experience, shouldn’t we seek a breadth of experiences? Most dance environments are rather homogenous in terms of types of bodies in the room. The intersection of dance and disability feels like the perfect place to tackle this. Dance is “of-the-body” by definition (meaning it doesn’t depend on an instrument, paintbrush, or camera). An art form that acknowledges the reality of the body and its many manifestations might be more successful in saying something that honestly and profoundly reflects how we live.

We hope this book provides the opportunity to give some thought as to what makes art inspirational, what makes technique beautiful, and what assumptions are commonly made about dancers’ bodies. What would the dance world be like if it acknowledged, embraced, and celebrated having at least 25 percent of its population be dancers with disabilities?

~~

1. “CDC: 1 in 4 US adults live with a disability,” Press release dated Thursday, August 16, 2018, <https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2018/p0816-disability.html>

One Response to “The Discussing Disability in Dance Book is Published!”

Looking forward to reading!

Comments are closed.