Bill Shannon: “Space, Light, Time, and The Human Condition”

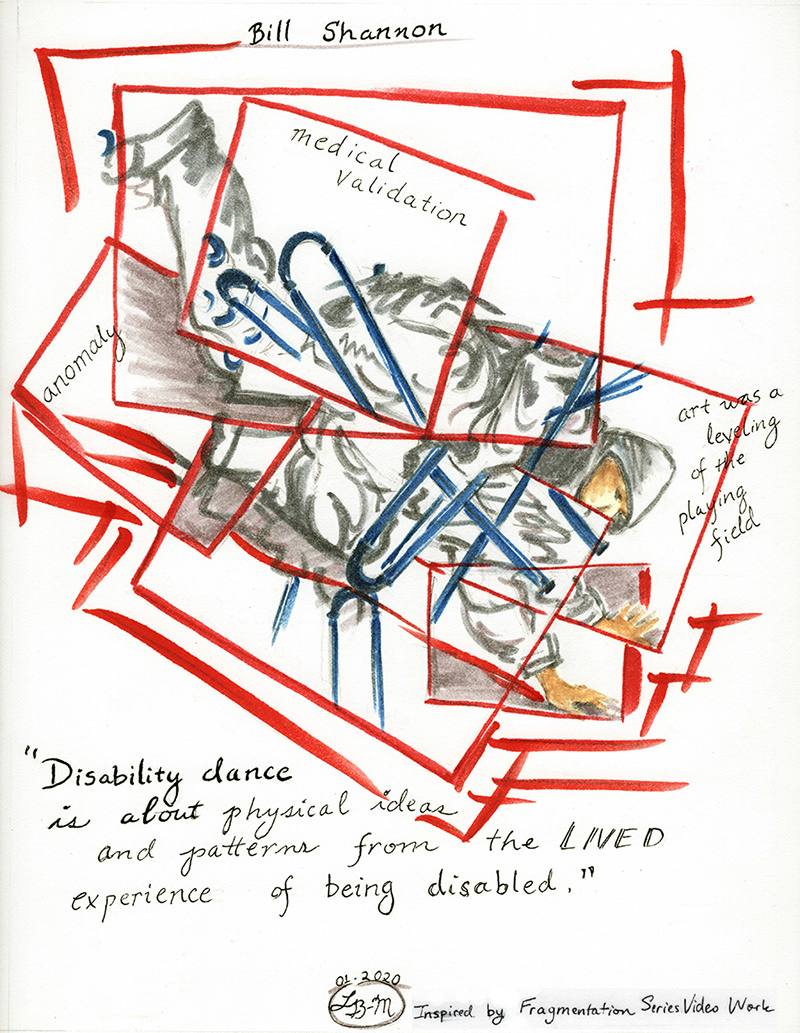

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT; ILLUSTRATION BY LIZ BRENT-MALDONADO

Bill Shannon is an interdisciplinary artist who explores body-centric work through video installation, sculpture, linguistics, sociology, choreography, dance, and politics. He has been awarded a United States Artist Award in Dance, a Guggenheim Fellowship in Choreography, a Foundation for Contemporary Art Fellowship in Performance Art, and has worked for Cirque Du Soleil. Bill created a specific movement vocabulary through his use of crutches and became a fixture at underground dance clubs for his contemporary kinetic expressions of hip hop and skateboarding. His singular style of mobility, performance, and dance required multiple new crutch designs to sustain technical advances in his movement.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!

Image description: Bill is depicted as if refracted through a kaleidoscope. He is wearing gray and using blue crutches. His head is mid right of the frame, his feet are top left of the frame, and his limbs are multiplied and amplified between. Red squares outline the various refractions of his body along with the quotes, “anomaly, “medical validation,” “art was a leveling of the playing field,” and “Disability dance is about physical ideas and patterns from the LIVED experience of being disabled.”

~~

How did you get into dance and what have been some highlights in your dance history?

Dancing was a part of my family life as a child. My parents were fulltime antiwar activists and organizers in the 70s and 80s. There were lots of meetings and protests with parties afterward where there was often live drumming. I remember dancing as young as five years old with my brace on my leg. My earliest connection to dance was the connection to music and the fact it extended from family and community.

I do not self-identify as a dancer. I identify as an interdisciplinary artist. I dance on crutches due to a physical disability, and that dancing is part of a larger body of performance and visual work. I look at my work as a pie sliced into different sections. The dance “slice” became more artistically successful than my other pursuits as an artist, though all the slices remain equally important to me.

Back to my childhood, art was a leveling of the playing field. In gym or recess, I was behind or picked last. Art class was a place where I could excel. It became my favorite thing in school. I was also very physically active. I was mainstreamed before mainstreaming was even a thing. My parents petitioned the schoolboard where I grew up in Pittsburgh for me to attend a school where there were no other disabled kids.

In the mid-80s, I lived and breathed hip hop and skateboarding culture. In the 90s, I started creating performance art with wearable sculpture under the name “Crutch.” It wasn’t disability dance; it was political performance art. When I moved to New York, I was re-immersed in the house, hip hop, and club music scene and started skating on modified “rocker-bottom” crutches. I entered competitions where I would dance on crutches in hip-hop, boogaloo, or house styles. In hip hop culture, you’re competing in a context of bravado and larger than life personality. My crew in NYC was called The Step Fēnz (pronounced “fiends”), who I met while street skating. They gave me the moniker “Crutch Master.” I was dancing very competitively against other dancers with similar grandiose handles and I considered it over time as an honor. The moniker fit for where I was as a street-based dance artist but was less fitting in other creative contexts. I retired it later when I stopped dancing competitively.

I was around for the birth of the disability dance scene and the early formation of companies like AXIS and Light Motion, as well as for the bourgeoning hip hop summits, conferences, and festivals. It was a split identity for me. Disability dance was primarily white and doing ballet and modern; I didn’t fit in culturally. Then there was hip hop, in which I was often one of the few or only white or disabled people entering the circles but did fit in culturally as far as relationship to music, fashion, language, and most critically the freestyle ethos of hip hop. These two worlds had very little crossover. I didn’t really fit in with the disabled dance community, and I was also an anomaly in the hip hop community. While accepted and appreciated by those respective and disparate communities, I never felt truly accepted as central to either.

How would you describe your current dance practice?

My practice has always been about solving problems. Currently, I’m working on the challenge of video art as a wearable medium through 3D printing by collaborating with a hardware coder.

Prior to that, I put together four group pieces that were concerned with the problem of translating the endless cipher of street dance into the proscenium. While I was doing those group works, I was also touring a solo with a DJ called Spatial Theory, which went through the elements of my movement style on crutches, like a journey through the challenges of presenting the many aspects of my invented form. While doing the solo and group works, I was also performing a series of street performances called Regarding the Fall exploring sociological phenomenology in relation to complex representations of disability in public space. The street performances led into presenting recordings of those street works to a secondary audience in a video lecture format to frame the invented lexicon I had evolved to discuss and define the problematic nature of the phenomena addressed in that work. The feedback from the street series and the lecture series from academia, critics, and audiences fed into Shannon Public Works Trilogy Window Bench Traffic, which was a series of street performances focused on authenticity of audience experience viewing street-based work without disrupting the street. I also had a series of fabrications of different crutches to support the challenges of the evolution of my dance and video installations for dance contexts as a visual art practice. Through all the above projects, there was also an ongoing series of line art drawings based on my conceptual pursuits in my artmaking called Notes on Performance. That’s the kind of interdisciplinary spectrum I continue to work within to this day as a dance practitioner.

When you tell people you are a dancer, what are the most common reactions you receive?

I don’t tell people I am a dancer. When people ask what I do, I tell them that I’m a trans-disciplinary or interdisciplinary artist and my work revolves around questions and conceptual pursuits.

If I don’t want to explain all that, I say I did choreography for Cirque du Soleil and I dance on crutches, which is a misrepresentation. Then they say, “Wow, really?”

What I did in dance was a technique 100 percent based in disability from childhood and based on the assumption of four points of weight distribution. It’s not a translation of another form; it is based entirely in disability movement history and influenced by kinetic and stylistic elements of hip hop and skate cultures. When I started dancing, disability dance was centered institutionally on wheelchair dance. If you were not using a chair or were able-bodied, you did not fit in very well. That was early on. In the past decade, I’ve experienced the shift of disabled dance into a broader spectrum of abilities and an alignment with queer theory and intersectionality. This transformation pushed the whole understanding of what a dancer is to the field of dance to a new place. Dance, to me, remains at its core the creative use of space, light, time, and the human condition.

What are some ways people discuss dance with regards to disability that you feel carry problematic implications or assumptions?

Because I was one of the earlier dancers with a disability to be covered by mainstream media, like the Village Voice and the New York Times, I was written about in ways I don’t think would happen now. Writers and journalists have evolved to some extent. Because I’m not just a dancer and I also do visual art where my body is not a factor in the work, I’ve been able to experience writing about my work when my body is in it and when my body is not in it. The most problematic element in the former is the idea that the impetus for the creativity is the challenge of disability and not just an inherent desire to create. At the root of that is, “Nothing could stop them,” or, “The condition drove them to…” That kind of language gives the credit for the impetus to be creative to a specific catalyst around disability. I find that especially true in dance because dance, even when it’s not about disability, is couched in the challenge and landscape of the body.

The main thing I would say is to be careful of writing about the artist as a human-interest story. When I read articles about disabled artists, I often feel that they are trapped in a human-interest story, wherein the first three or four paragraphs are about the human-interest of disability and those details and, by the way, there’s some art. That phenomenon needs to be looked at critically.

I invent language around my experience, and one of the terms I’ve come up with is “medical validation.” Until you validate the nature of the disability in medical terms to an audience, they are not listening to what you are saying. They are wondering what the medical details are of the disability. I noticed how, in my live performances, I’d see people searching through their programs. Or their gaze would shift – they’d see I kind of use my legs and wonder if I really need crutches. I realized that if I do an introduction medically validating my disability and explaining my technique, then most people understand better how to appreciate my work. The ambiguous nature of my disability necessitates some form of validation of the use of crutches as an assistive device and not just a dramatic prop.

Do you believe there are adequate training opportunities for dancers with disabilities? If not, what areas would you specifically like to see improved?

Dancers with disabilities are few and far between. What needs to happen to make things better for disabled people to even believe that they can have a dance career is what needs to happen to make things better for everybody: Medicare for all, tuition free schools, student debt relief, military budget reduction, drawdown of the extraction energy model, etc. Without these core changes, dancers with disabilities will have difficult lives and less access to training.

Would you like to see disability in dance assimilated into the mainstream?

No.

What is your preferred term for the field?

Because my arts community is sometimes uneducated yet also genius, they might not know the “right way to talk” about things yet are truly great people. I refuse to worry about terminology first or even second. Preferred terms come and go so I try not to get too attached to one or the other.

I don’t think there’s an absolute right way to talk about disability though obviously there are some unacceptable terms that are derogatory.

In your perspective, is the field improving with time?

In the US, UK, Canada, Japan, Sweden, Germany, Finland, etc. – these Westernized, capitalist, or democratic-socialist systems – there are layers of support with different entry points for disabled dance makers. So yes, talking in this spectrum of humanity, the field is improving. In other parts of the world, however, the arts are diminished. All our advances in the US exist in a political bubble of human rights that ends at the tip of a warhead attached to a drone buzzing over the heads of poor people in other less accessible parts of the world.

Any other thoughts?

In one of my latest works, I taught able-bodied people the patterns and technique of my disability-based choreographed movements. If you’re trying to learn a disabled form that is rooted in four points of distribution based on a crutch user, but you only have two points as legs without crutches, you’re put in the same position as a disabled dancer translating a dance created for able bodies onto their own disabled selves. Thus, the work became a political statement about disabled dance in history as it relates to the able-bodied canon. I am arguing through the process of this work that you don’t need a disabled body to perform a disabled dance. Disability dance is about physical ideas and patterns from the lived experience of being disabled. If others want to translate it to their able-bodied selves, it doesn’t make it an able-bodied form; it simply modifies the original.

Image description: Bill is pictured wearing a white jumpsuit with a cityscape and pink cloud in the background. He is perched atop his crutches, which form a triangle under him. His left hand is extended and pointing to the left of the frame.

~~

To learn more about Bill’s work, visit www.whatiswhat.com.

To learn more about the Discussing Disability in Dance Book Project, visit here!