Choreographing Invisible Labor

An Interview with Thomas Choinacky

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Thomas Choinacky is a queer interdisciplinary artist who creates avant-garde performance in Philadelphia. Here, he discusses his piece, Forehand Down the Line, which highlights the agility, absurdity, and queer movement of ball people in tennis. He shares how and why he investigates invisible labor and how it relates to queer identity.

While Forehand Down the Line has been postponed due to the coronavirus, it felt important to publish this interview anyway, particularly as it relates to invisible labor.

Forehand Down the Line rehearsal with Shizu Homma, Mal Cherifi and Alexandra Espinoza

~~

Can you tell me a little about your dance history – what kinds of performance practices and in what contexts have shaped who you are today?

I originally entered dance through theater. My bachelor’s degree is in theater, and I was particularly interested in physical theater. After graduating, I moved to Philadelphia. The work of Headlong Dance Theater was a space where I started to reevaluate what theater meant to me. I realized I wanted to use my body in new and integrated ways. I ended up working for Headlong for a number of years in an administrative capacity and built a relationship with the founders, David Brick, Andrew Simonet and Amy Smith. They were supportive of my artistic life. We talked about their artistic process, and those talks deepened my own artistic process.

I wanted to be more connected to my body, so I realized I needed to create my own score that I could always turn to when I felt disconnected. Between 2011 and 2014, I developed a practice around how my body responds to architecture. It ended up shaping the way I move and the pieces I make in so many ways. It’s called A User’s Manual, and it’s based on a book by Georges Perec, the French writer who wrote Life: A User’s Manual, in which each chapter highlights a single room in a giant apartment complex. I love the book. It inspired me to ask what it means to inhabit space and how my body is influenced by space. With this score I think and consider the space in my body in addition to external architectures.

How would you generally describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

It’s queer. It’s meditative. It’s spatial and architectural. It’s often autobiographical. There’s play. I often draw on my personal archive. I think about lineage: How I can perform lineage as well as what lineage I am pulling from when I tell a story?

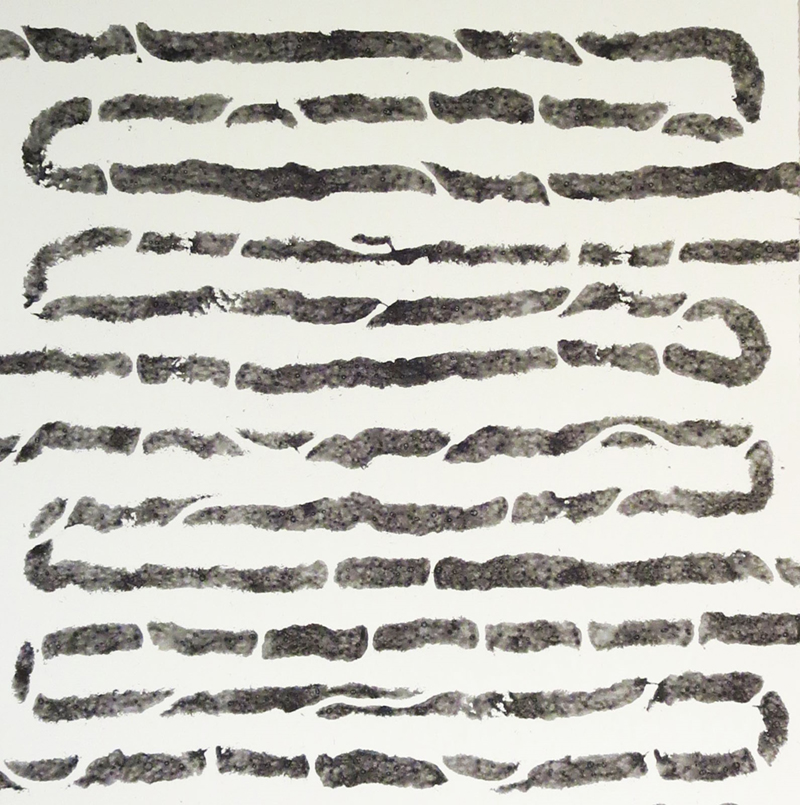

I’m also interested in failing at symmetry. I have a painting practice that is very choreographic; there’s lots of movement in it. I paint with a tennis ball as the painting tool. I try to make these patterns that are symmetrical but are always imperfect. There’s no such thing as perfect symmetry, and that plays into my choreography as well. When I set the same movements on different bodies, the movements end up different. An artist can attempt symmetry, and yet it can never truly exist.

Symmetry Study, painting by Thomas Choinacky

Can you tell me about your upcoming performance, Forehand Down the Line, and how the piece came about?

I am a tennis player as well. I went to watch the US Open tournament this past year, which was the first time I was at a professional tennis match. I was amazed by the choreography of the ball people. At the end of every point, the ball people collect the balls and have the balls ready for the server. They are moving the tennis balls around the court at the end of each point to be prepared for the next point. I was fascinated by this job that is unacknowledged because there’s someone who is framed as more important. Their movement is a dance in itself. It’s so specific, but attention isn’t granted to it. But being there live, spectators can look anywhere. It is its own performance.

I asked: What does it mean to take the movement of these people we don’t usually grant attention to, and put them at the center? What does it mean to give that attention and make visible this labor that generally goes unacknowledged?

What is your work process like?

The vocabulary of a ball person is so specific. It’s quite limited, so I pulled from that to create a small movement vocabulary for my dancers. I started to explore from there, taking these gestures and movements and doing them precisely with six dancers at once. From there, we created variations of the movement.

I took a workshop with Jonathan Burrows a number of years ago, and I feel this piece is influenced by principles I gained from that time. It looks at repetition and meditation around a very limited movement vocabulary, using limitation as an asset and not being afraid of boredom.

As the piece develops, it morphs. There are six dancers in the piece, and each performs the movements a little differently. It shifts from them doing the movement as precisely as possible to morphing the movement into the punk or pop version, for instance. There’s the shifting of both the familiar and unfamiliar, the way we know and the unknown.

How does your queer identity play into the work?

Most of the team identifies as queer, and I believe in sharing the stories of queer people. I feel in this work that it goes back to the failing of symmetry: There are people doing similar gestures, yet it’s not possible for them to be the same, and that’s what makes it so exciting. Each person is unique. Even though we’re seemingly telling the story of the ball people, we’re actually telling our own stories. Queer people aren’t often actually seen onstage for who they are.

What do you hope audiences take away from Forehand Down the Line?

I want them to reanalyze what we grant attention to. The broad question of the piece is around attention: What do we miss because we’re focusing on something else? This piece is opening a door to thinking about alternative perspectives. In a deeper way, there’s never just one version of a story. There are stories we don’t see or hear in a public sphere. A live tennis tournament is a public moment, yet there’s no primary attention given to the ball people. What does it mean to shift that? It’s proposing a new value system.

What kinds of audience members do you expect to come? Tennis players or dance lovers, or both?

I had a showing a few weeks ago where no tennis players were in the audience. I wanted to know how it translates, since so much of the piece is tennis lingo. I think someone who knows tennis will get something extra from the piece, but they are not my primary audience. I want an audience of people who are willing to ruminate on these movements. The piece is meditative. There’s something in the finiteness of the movement vocabulary that allows people to see, through repetition, how different the same movement can look on six different bodies. It’s like opening a door to see a variety of perspectives and abilities that were previously invisible.

Looking at your larger body of work, are there certain themes or issues that feel important to you to keep tackling or addressing?

I keep coming back to archive, in terms of my own personal stories as well as cultures I connect to and speak to. I like to look at how an archive or history is built and told. The archive can always change. Me telling one story is a stake in a transformation around what my archive can be, as well as the archive of the people who see my work. I usually do solo work because it’s more financially viable. Forehand Down the Line is the biggest piece I’ve done.

I’ve never actually been a ball person. However, there is something about the labor they do that speaks to me in a deep way. They’re working hard at being agile and fast, and yet it goes unacknowledged. There’s something about this piece that’s my own ritual or exercise in shifting attention and how I personally relate to performance. It teaches a shift in worth and value.

From A User’s Manual, photo Jen Cleary

~~

To learn more, visit thomaschoinacky.com.