On Native-ness, Decolonization, and Iterative Dance-Making

An Interview with Rosy Simas

BY EMMALY WIEDERHOLT

Rosy Simas is a Native contemporary choreographer from the Twin Cities area of Minnesota. Her new work, Weave, weaves through multiple cities and iterations. Here, she discusses white voyeurism of Native cultures, decolonization, and her process of iterative dance-making.

This interview took place via phone on August 9, 2018.

Rosy Simas, Photo by Tim Rummelhof for McKnight Fellowships, 2016

~~

Tell me a little bit about your history in dance.

Before I answer your question, it’s very important for me to always introduce myself. My name is Rosy Simas. I am Haudenosaunee, Seneca, Heron Clan. I consider that to be an extension of my name, because it is the people who claim me, not just the people who I claim. It’s a big part of who I am and how I see myself in the world. The other thing is that I don’t identify as Indigenous; I identify as Native.

How did I get started in dance? I think it’s interesting that people equate social dance and concert dance, as if cultural social dance, which in my case is the powwow dance I started doing when I was a child, is in the same field as contemporary dance, which is the field in which I work today. I think it has a lot to do with our Western views of how we skew things and put everything in the same field.

I think of myself as a dance maker, but I also work in the areas of film and set design. I additionally create visual art, which has been exhibited over the past few years. For myself and many Native artists, there is not a singular focus on one discipline; my artistic expression requires the involvement in more than one discipline, but those disciplines are defined by Western European standards. There’s this idea that if you’re a basket maker, you can only be a basket maker, or if you do bead work, you can only do bead work. But that doesn’t actually fit how most Native artists work. For instance, most people I know who do powwow dance also make their own outfits. Beyond dancing, they also sew and bead. I just want to point out there’s a skewed idea of what is the field.

I do primarily work in the contemporary dance field. I do have contemporary dance training, which began with ballet and modern in the 1980s in high school. I grew up in an urban Native community in the Twin Cities in Minnesota. I later studied contact improvisation and improvisation in the somatic field, so I also have those influences, which are a part of my craft. And there’s also theater, which is part of my interest in stage design. This is my Western training.

I would like to contextualize my work as a choreographer in the field of Native contemporary dance.

Rosy Simas in We Wait In The Darkness, Photo by Ian Douglas, Movement Research at Judson Church, 2014

Too often when people discuss the origins of the fields of Native modern and contemporary dance, those fields have been historically written about as being the supposed fusion of powwow/cultural dances and modern dance, in a very dance-theatre narrative type of mode. This is problematic because there are Native choreographers who are making work, such as Emily Johnson, myself, Tanya Lukin Linklater and others who are important voices in the field of Native contemporary dance, who are not making dance theatre, and not working from such an assumed fusion origin point.

Work is being made which has a Native narrative center, focused on contemporary stories, that exists beyond what non-Native people expect Native choreographers to be making work about and the ways we supposedly should go about making it.

How would you describe your work to someone unfamiliar with it?

My work is very much about attention and listening. It has a meditative quality. I have an aesthetic developed out of attention and intention.

There are many elements to the work. I collaborate primarily with a French composer who works with us intimately, not in the classical way in which the composer makes work and sends it to us. The music, which is called generative, is created during the process in which we are making the dance. The film is created in a similar way. The sound is what I would call immersive quadrophonic sound. The idea is that the audience is in the same soundscape as the performers, so they have a similar visceral experience.

I work a lot with concepts that are both scientific, philosophical, and personal. Right now, we’re working on a piece that looks at the question: How do I know who I am in my body? This is both a simple and complex question. Movement gets generated from that question, and we look at how movement motifs come from a deep internal place to a more external sharing. From there, the score becomes layered.

We start with basic tasks, which might be listening or building a relationship to sound. We work a lot on training the body to have a heightened sense of awareness of sound and relationship to other people. We work as an ensemble before we break out to duets or solos, so we build relationships.

Space and time are an important element to my work in the sense of thinking about how recurring movement generates a particular type of energy, and how that energy moving through space can shift time and how we perceive time. The idea is composing space and time.

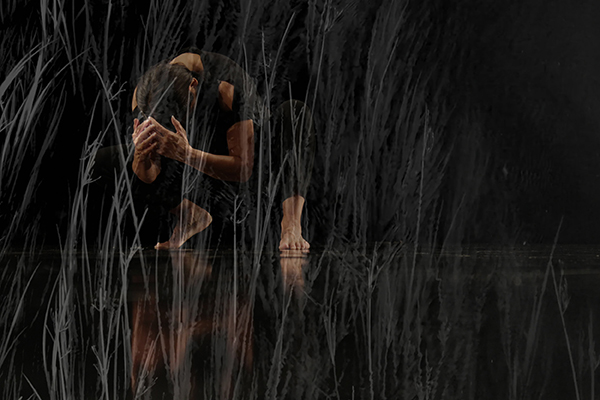

Rosy Simas in Weave, Photo by Imranda Ward, Design by Rosy Simas, McKnight Fellowship/MANCC Residency, 2018

How do you decide whom to work with?

It depends on the work. Each piece is different. The piece we’re working on now, Weave, is probably the most open piece conceptually I’ve done the past few years. I work with François Richomme, the composer, because we’ve been working together for a while and it’s still my interest to be working with quadrophonic sound.

The performers are a mixture of both people I’ve worked with in the past and people who are new to working with me. I don’t have a mandate about working solely with Native or Indigenous people. I say that because there’s this idea that should happen. I do sometimes work with Native or Indigenous people, but the work calls for whomever it calls for. My work is created through a Native feminist lens. The work is Native because I’m Native, not because of the people who are in it.

This particular work, Weave, include performers from Singapore, Yaqui [a Native tribe], African American from Minneapolis, Nova Scotia of European descent, and Colombia. Two of the people I work with are adoptees. I also work with two Native writers, one who identifies as mixed-race and the other is Ojibwe. They are an important element in contextualizing the work, all the way from the conception of the ideas guiding the work to raising money and developing materials to go in the program. They write both creatively and philosophically. This is important because I want the work to be written about by Native people or people of color. Part of that has to do with the fact that the majority of scholarship on Native contemporary dance is written by white people.

George Stamos, Sam Aros Mitchell and Valerie Oliveiro in Weave, Photo by Douglas Beasley Photography, 2018

Are there ways in which your work has been written about – either reviews or social media – that you feel carry problematic assumptions about Native populations?

Yes, in both language and concepts. There’s an insistence on comparing Native dance artists to one another. For me, this is problematic because I view Native nations on Turtle Island [North America] as having international relationships. We all may be indigenous to this place, but we all have distinct cultures. There is a desire to put people within a group and then compare and contrast. This is a difficult subject for me. There are things I don’t think white dance scholars who write about Native artists can ever understand. That’s just my perspective; a lot of Native dance artists are happy for any exposure to a broader audience, and for good reason. There’s a willingness and eagerness to discuss and share their work with larger populations so an awareness is raised about the field in general.

As a result, there is a constant allowing of non-Native people to interpret what we’re doing and be the ones who put that information out there. This amounts to contextualization to a degree. With Weave, I’m working intimately with writers, probably more than the dancers, because it’s a new process for them.

Who are our Native students who are writing in the field and how is their scholarship being nurtured?

White privilege, for me, is about taking opportunities, as opposed to utilizing one’s position of power to create opportunity for Native scholars and artists. We need to be looking at this specific issue: Who is framing the work, and who is the work for? How does an artist envision their audience, and how does that determine the content of the work itself? It’s the same thing for an author. When you write a book, you have a perceived audience. You see who those people are in your mind as you craft the work.

Historically, Native contemporary dance has been made to create exposure which, to me, means making work for non-Native audiences to better understand Native cultures. That is obviously important, but it reinforces stereotypes and continues to play into the system of white supremacy wherein people with white privilege pay to have a Native experience. This is a very voyeuristic way of approaching Native artistry. It’s historically what has been done by scholars, anthropologists, and archeologists. Non-Native people have built their careers and gained personally writing about and doing research on Native people.

Native people are still oppressed and are still not being heard. Our culture is being stolen from us by people pretending to be Native or via cultural appropriation. I can’t think of any other people who experience those two things simultaneously and continuously.

You mentioned who the work is for. Can you expand on that?

There are people who would love to say they’ve achieved respectful and accountable relationships with Native audiences, but I don’t think it’s true. It’s something to aspire to. It takes more time and it takes more money. It’s ongoing work.

I live in an urban Native community. I grew up in it. I’ve always known who I am. I don’t have an ambiguous Native identity. I grew up with Ojibwe elders even though I’m Seneca, and I was named in both Ojibwe and Seneca. I have had a cultural upbringing. My grandmother was one of the founders of the San Francisco American Indian Center. For me, being Native is who I am; it’s never been something I needed to discover about myself. Building a relationship with my community is going to mean something different to me than it is for another artist.

What it means to me is: When I think of who I make my work for, I think of the five Native people in the audience. I am hopeful there might be 10 or 15 Native people there. But they are the people who I make my work for. There may even be two elders who are in my mind the whole time I am making work, as if they are going to experience and respond to it.

By doing that, my hope is that the audience in general has an experience which is not voyeuristic anymore. What they are watching and witnessing is an authentic relationship between me and those Native people in the audience. The general audience is included in that space, but the work isn’t meant for them. These are philosophical questions. It’s important to constantly have inquiry about who is my audience and how I connect to them. What kind of experience do I want them to have? I want non-Native people to not have a voyeuristic experience. I don’t want them to have an experience in which they think they are having a Native experience that is somehow separate from me, Rosy, the person.

Zoë Klein in Skin(s), Photo by Carrie Rosema/Indigenous Choreographers at Riverside, 2016

In our process, we have open rehearsals and practice iterative work. The work is shown in whatever form it is in, for whichever presentation we are doing on the tour. My work doesn’t premiere. It only premieres in language for a certain venue because it’s a stipulation of my contract and a requirement by the funders. Through my work and the constant asking of questions, I’m developing relationships with funders that cause them to question their own language and requirements, but it’s a slow process.

Do you feel the field is improving with time?

It’s all over the board. There is no place I go in which someone does not come up to me after a show or workshop and tell me that their great-grandmother was Cherokee. There’s no panel I’m on in which someone doesn’t raise their hand and ask a question that has to do with them personally. I can’t control whether those people come to my show. Those people are always going to come and have a voyeuristic experience because those people are the center of their world. That is a part of the greater culture, the “me” culture. Those are not values I grew up in or live by.

Of course, a large part of me is Western. I am American. That is a citizenship besides being Seneca. There is always the duality of both. I would never say my work is only Native. I have plenty of Western influences in my body and in my work because I live in a Western culture.

It’s very popular right now to talk about decolonizing the body, but what does that really mean? The first step is to be honest about the different influences one is working within as an artist. I’m not trying to be flippant, but I think it’s an important aspect of what is happening.

I do say in my text that the movement I am working on is decolonizing the body. I have great philosophical questions with my friend George, who is white, about whether he can decolonize his body. I don’t know, I don’t have these answers. But I think there is a lot one can understand about oneself by being in practice with people asking these questions.

For me, it comes down to this practice of attention and intention. It goes back to the question I’m asking in my next work: How do I know who I am in my body? Those kinds of questions begin to get at this idea of decolonizing the body. It’s okay to not know, but this is not a place people feel comfortable. They want definitive answers, especially when it comes to Native culture, Native artists, and Native scholarship. They want to know what it is. The circular-ness of discovery is scary. There is no technique one can master in this respect, like beginning, intermediate, and advanced decolonizing of the body.

What are you working on next?

Weave is being created in this circular model. It begins in the Twin Cities and then it goes to Alabama, but it doesn’t go to Alabama in the same iteration. I’ve spent six weeks allowing the place to inform the work as it is now, and the iteration we will present at the Bicentennial of Alabama. Then we go to Philadelphia, the home of the Quakers, great allies of the Seneca people. Our territory extended into Pennsylvania. I have a relationship to that place, which is different than the relationship I have to Birmingham, which is different than the relationship I have to the Twin Cities. Each performance becomes an iteration of that relationship. Then we go to Maui and O‘ahu and work with community over a longer period. We’ll do two separate iterations there, and then six months later we’re in Washington, D.C. It’s never a culmination, but there’s a circularity in how those iterations weave through the work itself.

Zoë Klein in Weave, Photo by Douglas Beasley Photography, 2018

~~

To learn more, visit www.rosysimas.com.